Econ 210a :: Why the Agrarian Age Stayed Poor: Just What Was the Long-Run Trap Anyway?

What kept the rate of growth of human “technology” at less than 3% per century back before the year 200—and progress not guaranteed, as the Late Bronze Age collapse and the post-Roman-Han Dark Age tell us? And, after that, kept it at 8% per century from 800 to 1600, compared to our 2% per year today? Was it not t enough thinking heads, a structure of domination that scorned innovation that was not immediately useful for political ends, or something else? Musings before class on Wednesday, February 11, 2026…

Today is week 3 of my tranche of the “Introduction to Economic History” for first-year economics graduate students, the course this week I am sharing with Chenzi Xu.

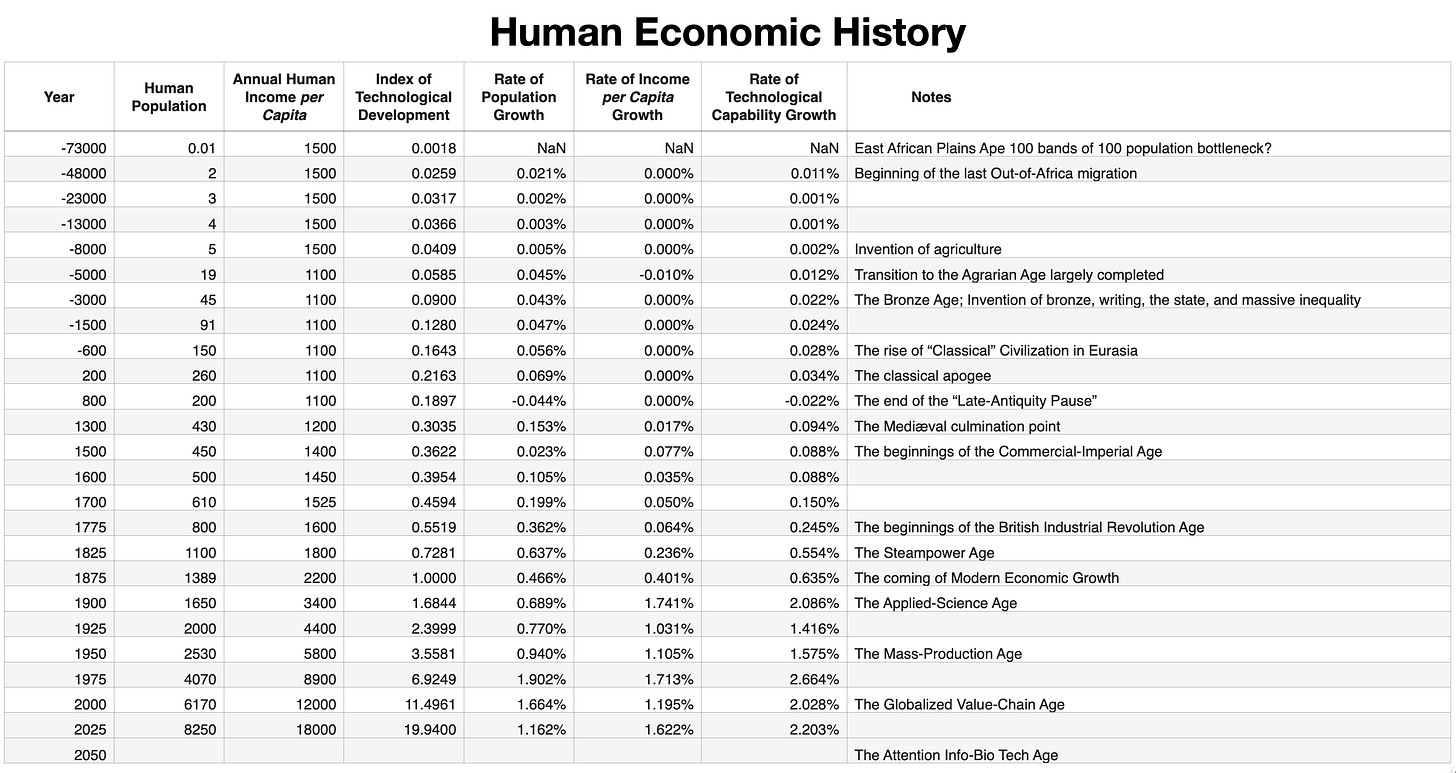

I am keying off of my guesses as to how to try to quantify the longest-run shape of human economic history—population, productivity levels/living standards, their rates of growth, and then the rate of growth and the level of an index of “technology”—the human capability to manipulate nature and coöperatively organize ourselves that we have discovered, developed, deployed and diffused across the world for the benefit(?) of humanity considered as an anthology super-intelligence with now an extraordinarily fine physical and cognitive division of labor:

These are, as I said, guesses. They are not just empirically but conceptually shaky. How would one measure the value of “technology”, understood as the value of the stock of ideas that are now humanity’s collective property and that turn out to be useful in our physical division of labor?

I guess that the rate of growth of the value of this ideas stock is equal to the rate of growth of measured output-per-capita plus half the growth rate of population: that ideas are twice as salient as resource scarcity in enabling productivity.

But if you have a better guess, I would be very happy to adopt it.

There are also deep conceptual problems in the real output-per-capita guesstimate. It is, roughly, our collective power to produce necessities and simple conveniences—what we need in order to survive, reproduce, and not end each day exhausted and in substantial pain from RSI and other injuries. But it does not take proper account of the extraordinary range of what every previous generation would call extravagant luxuries. And variety matters. There is an argument that if one tries to build a sensible model of the value of variety and of experience, one winds up with something like real output-per-capita times the variety of commodities you consume times lifespan. If that is our rough measure, than we today are not 16 but rather 16 x 10 x 4 = 640 times as “rich” as our preindustrial ancestors—and those of us among the richest tenth of the world today are 3200 times as “rich”.

But what could such an excessive quantification actually mean? Other than “it is a real big difference, so big that there is no doubt that quantity has turned into an unbridgeable qualitative gulf here”.

That is the background: an expansion of humanity from 10,000 people (sort-of) 75000 years ago to 5 million 10000 years ago on the cusp of the invention of agriculture; demographic expansion from 5 million 10000 years ago to 500 million 400 years ago with a loss of income per capita for the non élite hewers of wood and drawers of water; technological progress very slow—less than 3% per century up until 800, and even that was not guaranteed as 200 to 800 shows us, and then 8% per century in the Mediaval 800-1600 era; followed by progress at a rate of 20% per century over the Commercial-Imperial 1600-1775 age, 80% per century over the Industrial Revolution 1775-1875 age, and at 2% per year—a 7.4-fold amplification over a century—in the Modern Economic Growth era since, not taking full account of the amplification of the variety of luxuries and the increase in lifespan.

In this context the big questions for class today are: