Graduate Economic History: Spring 2026 (DeLong Segment)

From Ensorcelled by the Devil of Malthus to Modern Economic Growth: Twenty Windows on Five Thousand Years of the Economy: a reading-intensive tour from pre-agricultural societies up to today, starting with Robert Solow putting “supply and demand” into their proper institutional-historical context, & ending with Claudia surveying the “human capital century”. And, in between, a faster and more violent than merely whirlwind tour: “My God! I looked out the window, and I missed the Reformation!”-style…

I am teaching half of UC Berkeley Econ 210a this semester. I find that there are 20 topics I really, really want to cover within the potential subject areas of the course that have been marked out for me. I have seven two-hour classes. So I can do it if I manage to do three topics per class. The question is: should I try to do all 20, or should I slim down the list of topics?

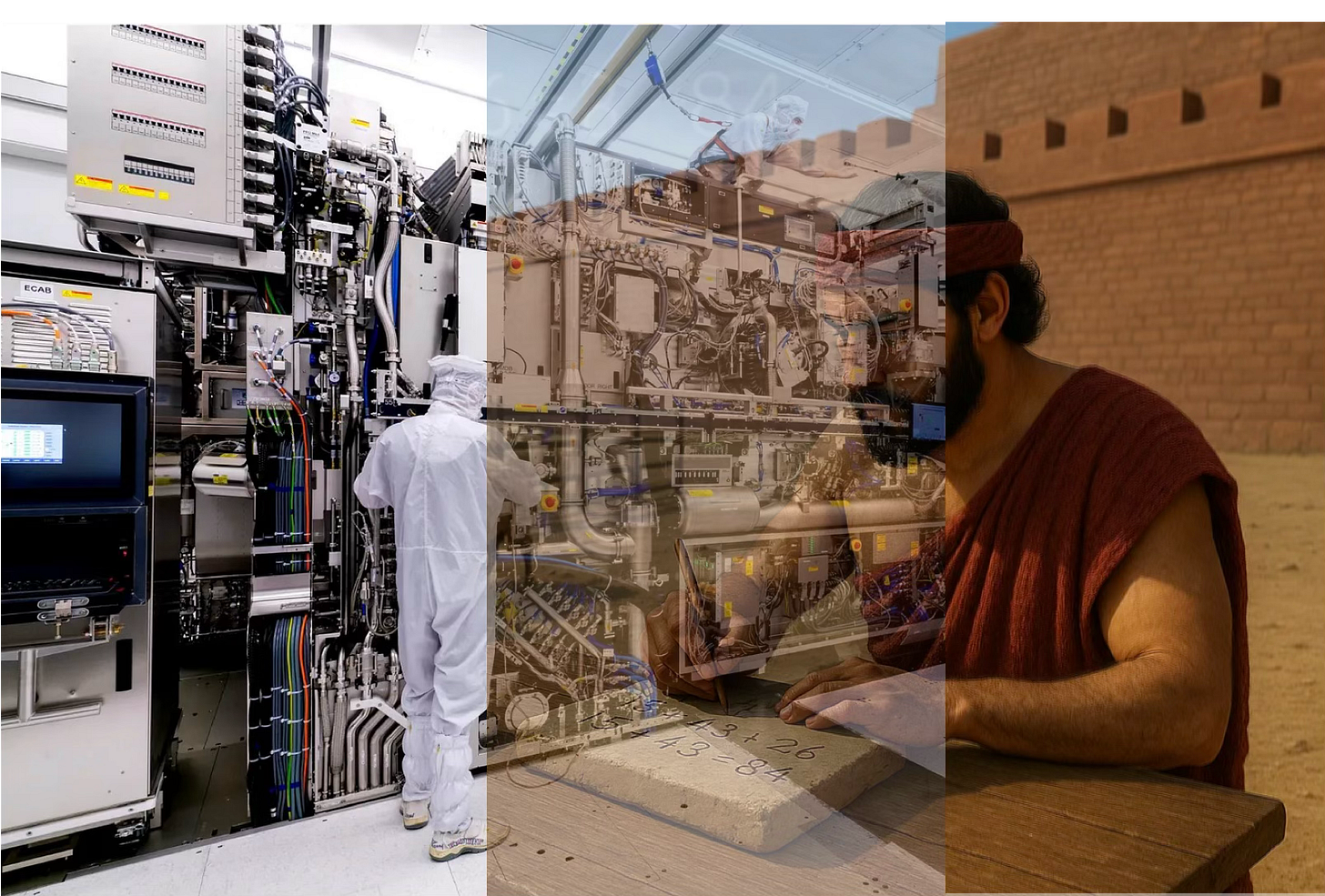

My portion of the course is a demand that students take the long view of the economy: not the next quarter’s GDP release, not even the next election cycle, but more than five-thousand years of humans trying—often fumbling—to wrest a tolerable life from nature, technology, and each other. The readings are not a canon, but a curated set of arguments and measurements that let us ask, with some seriousness: why did the world stay so poor for so long, why did that change, and why has that change been so uneven and so fraught?

Here’s how I might introduce my set of readings and topics, if I decide I should do it in a lump:

We begin by putting the economist’s favorite toy—supply and demand—into its proper historical box. Solow’s short, sharp essay on “Economic History & Economics” reminds us that our models are, at best, compressed stories about worlds that once existed and may never exist again.

Thus economic history is not a branch of applied theory; it is instead our “treasure for all time”, κτῆμα ἐς ἀεί.

From there we descend into the very long stagnation of the agrarian age:

Steckel’s biological measures and Clark’s centuries-long series on English living standards show us a world in which, for millennia, technological advances and productivity gains mostly bought more people, not better lives. Diamond’s deliberately provocative “Worst Mistake in the History of the Human Race” and Morris’s social development indices push us to ask whether the shift to agriculture and settled states was, from the standpoint of human flourishing, an unambiguous step forward at all. Together, these pieces are meant to unsettle any easy Whig story in which history is a simple march toward betterment.

We then take up the question of why this Malthusian trap held so long—and why it eventually loosened: