Lessons for Debt Control from Clinton's Success in the 1990s

Time to fly my left-neoliberal freak flag! For a failure to get the history right may well lead us to inaccurate conclusions about what our government-debt outlook really is, & mistake how resulting economic & political-economic problems should be dealt with:

Credible fiscal anchors crowd in private investment when the central bank leans against demand shortfalls and technology makes capital cheaper. Clinton’s OBRA 93 deficit-reduction Reconciliation package accelerated the economy, because macro reality beats tribal signaling. Fiscal credibility, pro-work redistribution, and a supportive Fed plus falling ICT prices crowded in investment, the 1994 yield-curve shift move reflected growth strength and MBS mechanics, not fears of “austerity gone wrong.” The Clinton 1990s really were a fabulous decade that delivered rising employment, low inflation, and real wage gains, with the EITC expansion the single biggest pro–working-poor social-insurance expansion. Labeling this “austerity” misses how structure + demand + technology produced more capital, higher productivity, and a richer America.

And taking claims that Clinton’s OBRA 93 would tank the economy as real fears by credible macroeconomic analysts is to mistake political bullshit for real analytical judgements and warranted fears.

I write because I think the very sharp Marcus Nunes gets this one wrong here.

He is reviewing the the fiscal adjustment that was the Clinton 1993 Reconciliation deficit-reduction bill—OBRA 93 <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Omnibus_Budget_Reconciliation_Act_of_1993>

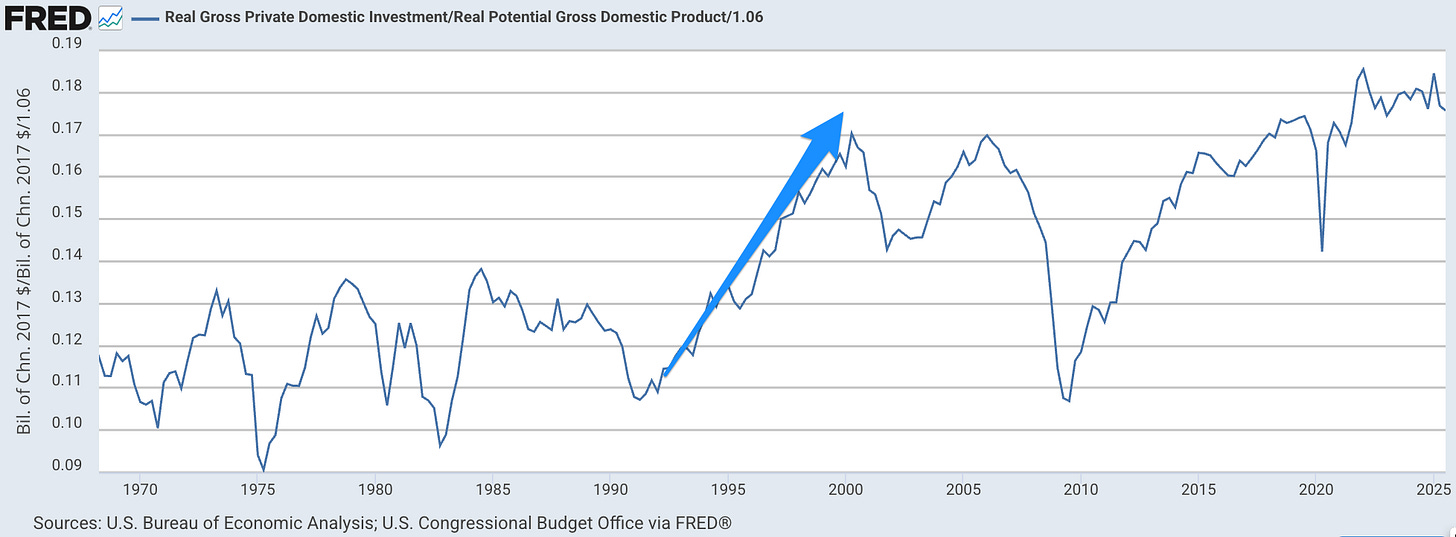

It crowded-in a truly extraordinary boost to investment in America, which was further amplified by the secular fall in the relative price of information-communications capital goods that was the internet boom. And American economic growth was, thereafter, stronger by perhaps 0.5%-points per year. Figure that America today is 15% richer because of Bill Clinton and those of us who worked for and supported him.

OBRA 93 was viewed by us left-neoliberals—us Rubin Democrats—who pushed this in 1993 as very much a second installment of what had been OBRA 90: the George H.W. Bush-Mitchell-Foley deficit-reduction package of three years before. OBRA 93 did have more tax increases and fewer spending cuts in the mix, but by a narrow margin. OBRA 93 was more progressive than OBRA 90, but again by a narrow margin. But both combined revenue increases with spending restraint rather than relying on one side of the ledger alone, both raised top‑bracket income tax liabilities and closed loopholes/preferences to broaden the base and increase progressivity, both tightened discretionary spending caps and enforced them with sequestration/PayGo‑style budget rules to deter backsliding, both protected core social insurance pillars while trimming growth rates in selected programs rather than cutting benefits outright, both sought business‑confidence effects by committing to predictable multi‑year deficit paths to “crowd‑in” private investment, and both were sold as responsible long‑run policy over short‑run optics.

Indeed, the theses of us left-neoliberals—us Rubin Democrats—who pushed this, and convinced Clinton to throw his weight and his administration 100% behind it, was that:

it would indeed crowd-in investment and boost economic growth,

we had a commitment from Alan Greenspan at the Federal Reserve that he would do his damnedest to adjust monetary policy so that recovery from the 1990-1991 recession was not interrupted by any shortfall in aggregate demand,

neglecting the urgent need for deficit reduction might well wind us with much higher interest-rate risk premiums that would disrupt economic recovery,

because there were signs in financial- and exchange-market reactions to news that the U.S. debt was rising high enough to endanger the dollar’s safe-haven status,

we would get votes from sensible deficit-hawk Republicans and so it would become a “bring us together” bipartisan initiative,

success at boosting the pace of American economic growth would mean that, after a 1990s of the first rapid real wage increases in a generation, those who had become Reagan Democrats in the 1980s would be much more willing to support equity policies as they would no longer feel under as much family financial stress.

(6) was 100% wrong.

(5) was 200% wrong—it turned out that there were ZERO sensible deficit-hawk Republicans: none were willing to accept balanced deficit reduction hitting both spending cuts and tax increases, even though they would talk a good game in the abstract.

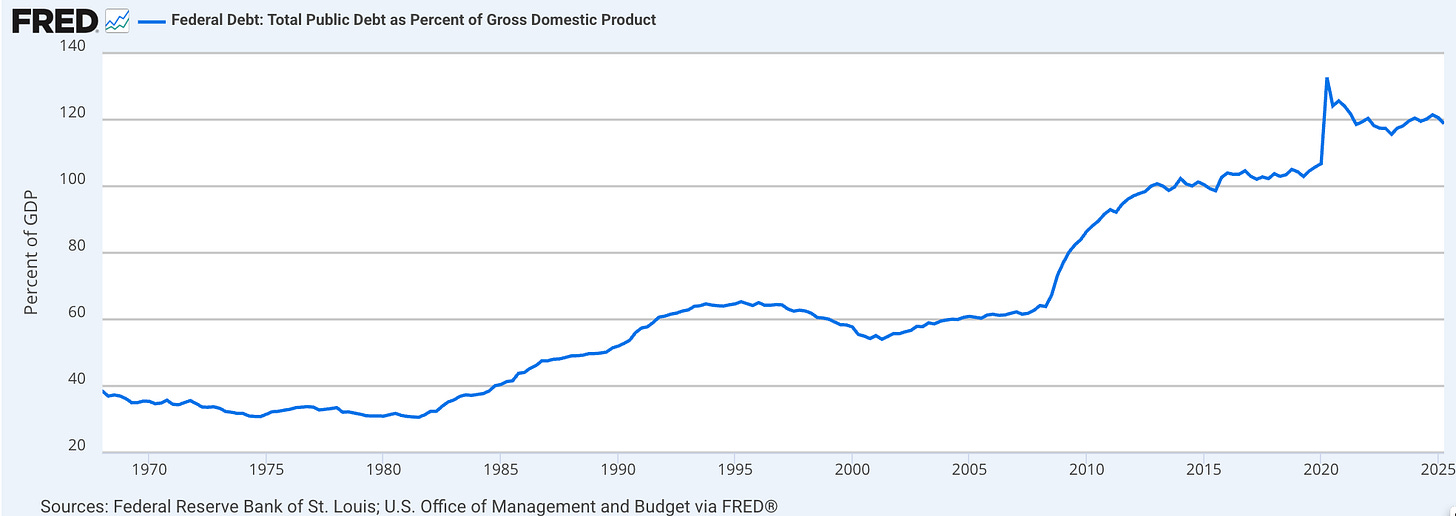

(4) was something I was 100% certain of at the time—and maybe it was true then that the safe-haven exorbitant-privilege debt capacity of the U.S. was then not that much more than 70% of annual GDP. But, if so, debt capacity rapidly and extraordinarily expanded once the 2007-8 GFC hit the world economy:

(3), thus, has to be put in doubt. It was an argument I very strongly believed back then. I recall a cold December 1992 night I spent carrying (a) simulation runs projecting interest rates implicit in the then-current yield curve under fiscal business-as-usual and (b) assessments of how the Bush 41 administration had begun to see “bad news” about the deficit not strengthen but weaken the dollar over to Bob Reich’s house, so he could carry them down to DC for Transition-Planning meetings. I still believe it was a risk. But I cannot believe it was an overwhelming risk.

However, (1) and (2) still look very very good indeed. And those by themselves are enough to place us, all of us who worked on and supported OBRA 93 public benefactors, among those whose names are written brilliantly and boldly in the Book of Life—especially as Gene Sperling managed to get and keep in OBRA 93 the EITC expansion that was then and is now the biggest pro-working poor expansion of the American social insurance system ever.

But we got zero Republican votes for OBRA 93. OBRA 90 had passed the House 227-203 (Democrats 217-40, Republicans 10-163, but with an unknown number of Republican “yeas’‘ in reserve if needed) and the Senate 54-46 (Democrats 44-10, Republicans 10-35). OBRA 93 passed the House 218-217, and the Senate 51-50, all Democrats both times.

So here is Marcus:

Marcus Nunes: The Transition to Fiscal Dominance <https://marcusnunes.substack.com/p/the-transition-to-fiscal-dominance>: ‘In the 1990s… a rising debt ratio since 1980 was reduced… by Bill Clinton and the congressional Democrats]… through significant “austerity”, with both goverment spending falling and government revenues rising…. Monetary policy was appropriate, managing to keep NGDP on a stable level growth path, while inflation was low and stable. Throughout the adjustment unemployment was falling and reached 3.9% by the time Clinton left office…. However, there was significant economic debate—and widespread professional concern—that Clinton’s fiscal consolidation would damage growth. Many prominent economists predicted the 1993 deficit reduction package would cause recession or stall the recovery from the 90/91 recession. Just to give a few examples of ‘big names’ that were skeptical:

1. Republican Economists’ Consensus View: The Republican economic establishment was nearly unanimous: this would damage growth. Herbert Stein (Nixon/Ford CEA Chairman): Warned the tax increases would slow recovery. Martin Feldstein (Reagan CEA Chairman): Argued higher taxes would reduce investment and employment. Predicted the package would “significantly reduce economic growth.” Robert Barro (Harvard): Concerned about growth effects of higher marginal tax rates on labor supply and investment. Michael Boskin (Bush CEA Chairman): Predicted negative growth effects, particularly from top rate increases affecting entrepreneurs and small business.

2. Wall Street Consensus: Major investment banks and forecasters predicted slower growth: Goldman Sachs economists initially forecast the deficit reduction would subtract ~0.5 percentage points from GDP growth. Many Wall Street economists worried the fiscal tightening would abort the fragile early-1990s recovery. Bond market initially sold off on fears that fiscal consolidation would hurt growth, reducing tax revenues and making deficit reduction self-defeating.

3. Political Predictions: Every single Republican in Congress voted against the package, many citing economic harm: - Senate: 0 Republican votes (50-50, VP Gore broke tie). - House: 0 Republican votes (218-216). Newt Gingrich predicted: “The tax increase will kill the recovery… This is the Democrat machine’s recession, and each one of them will be held personally accountable.” Dick Armey (House Majority Leader): “The impact on job creation is going to be devastating.” Phil Gramm (Senator): “I believe hundreds of thousands of people are going to lose their jobs… I believe Bill Clinton will be one of those people.” (In 1996, Clinton was reelected!)…

(Parenthetically, not mentioned by Marcus: John Kasich of Ohio, back on July 28, 1993: “This plan will not work. If it was to work, then I’d have to become a Democrat and believe that more taxes and bigger government is the answer…” <https://crywolfproject.org/quotes/quote-%E2%80%93-rep-john-kasich-r-oh-cnn-1>. John Kasich lied. He never became a Democrat.)

Now let me pick my bones:

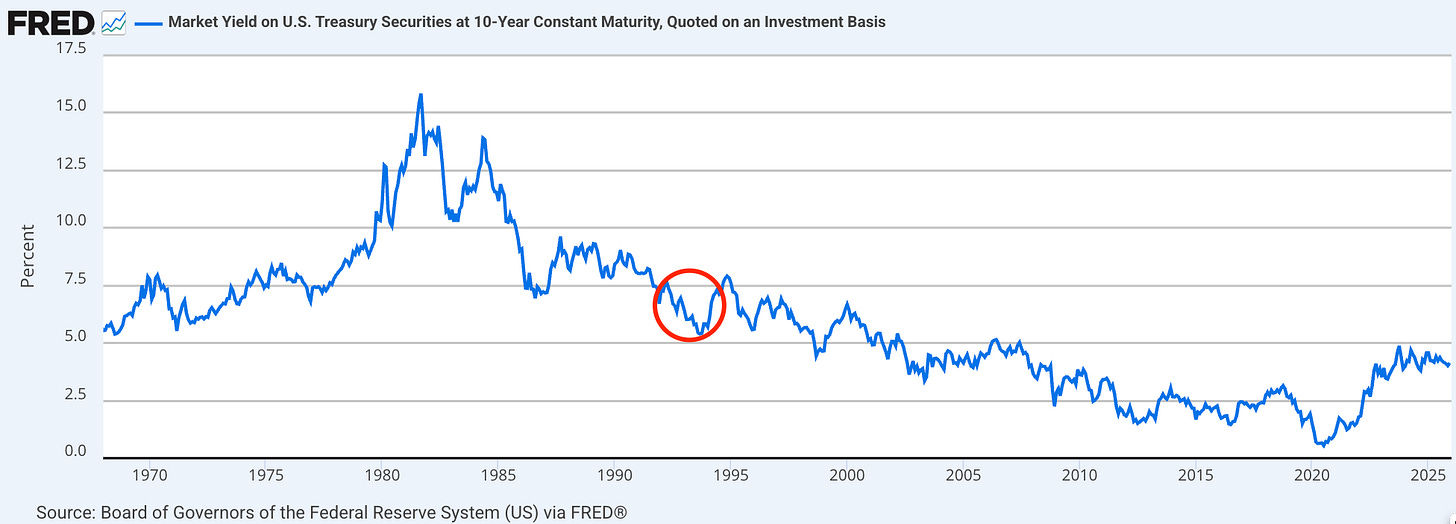

First, damned if I know why Marcus writes “Bond market initially sold off on fears that fiscal consolidation would hurt growth, reducing tax revenues and making deficit reduction self-defeating.” Look at the 10-Year Treasury:

Damned if I can see any bond-market selloff as George H.W. Bush went from clear favorite to win reëlection to loser, and as Clinton shifted to his left-neoliberal deficit-reducer incarnation, as OBRA 93 moved through the congress with only Democratic votes and with only one-vote victories in either chamber, and as it then began to take effect.

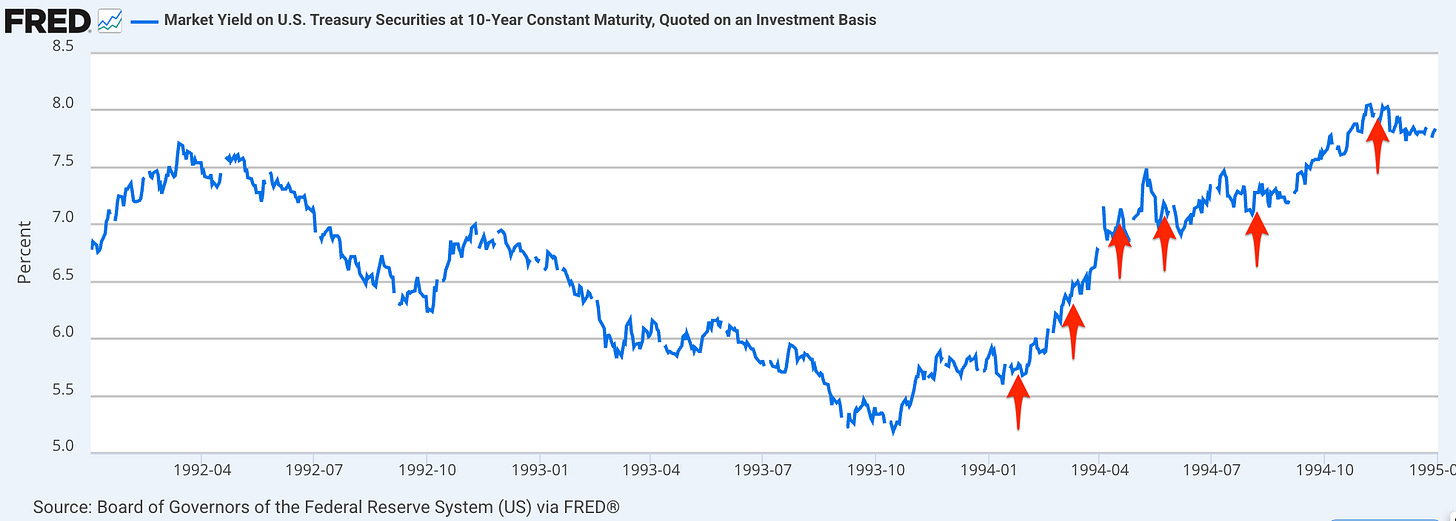

Zooming in, adding in the dates that Alan Greenspan raised the Federal Funds rate:

The bond-market selloff came starting only half a year after the passage of OBRA 93, and was a reaction to two things: (A) The first was the extraordinary strength of the U.S. economy, as high-tech emerged as a leading sector and as investment in information and communications technology roared ahead greatly in excess of our expectations. (B) The second was the endogenous duration of mortgage-backed securities, which were then a new thing: as interest rates rose, people stopped refinancing mortgages, holders of MBS found themselves holding assets of much longer duration than they had counted on, and so they dumped long-duration Treasuries into the market; the consequences was that instead of a 1-to-4 gearing of 10-Year to 3-Month interest rate increases, we were surprised by a 3-to-4 gearing.

Both (A) and (B) struck us by surprise, and they made my life working for the Treasury in 1994 extremely interesting—very stressful—and never dull.

But the bond-market selloff did NOT, REPEAT NOT, reflect any fear that “fiscal consolidation would hurt growth, reducing tax revenues and making deficit reduction self-defeating”. The deficit was, by then, falling much faster than according to the benchmarks our initial 1993 forecasts had set.

And the Wall Street economist fears—well, Greenspan was 100% on board with deficit reduction and OBRA 93, and so we interpreted those worries (and the Goldman-Sachs forecasts) as coming from people who were not so much making forecasts of the consequences of a combination of fiscal austerity and monetary ease, but rather people making noises to put themselves into ideological alignment with their largely-Republican client base, by parroting what the Republican politicians were saying.

And the Republican politicians? The Doles had been powerful drivers and advocates of the Bush 41 deficit-reduction package, OBRA 90, three years before OBRA 93. Had OBRA 93 been proposed under a second-term Bush 41 presidency, they would have been strong advocates as well. It was, in their view, good policy. But because the person at the head of the government was not Republican George H.W. Bush 41 but Democrat Bill Clinton 42, root-and-branch opposition to it was good politics. As for the Gramms, the Gingriches, and the Armeys, they were not making forecasts but rather one-way bets: if the economy went into recession for any reason, their predictions that OBRA 93 would be useful; if the economy did not, they knew that the supine press corps would never hold them to account. And it did not.

And now we come to the Republican economists. Were Stein, Feldstein, Barro, and Boskin serious in their fears that OBRA 93 would damage economic growth? Barro, yes. But Stein and Feldstein had been big OBRA 90 boosters, and Boskin had been an OBRA 90 designers. By far the most significant difference between OBRA 90 and OBRA 93 was the partisan identity of the President who would sign it into law. Now I suppose it is possible that Stein, Feldstein, Boskin thought that OBRA 90 was bad policy, and only went along with it because they were team players—professional Republicans. It could be. I never asked any of them. But my hunch is that it is overwhelmingly more likely that the polarity is reversed: that it was their opposition to OBRA 93 rather than their support of OBRA 90 that was subservience to their political masters.

Thus I think Marcus has it more-or-less completely wrong when he says that “there was significant economic debate—and widespread professional concern—that Clinton’s fiscal consolidation would damage growth. Many prominent economists predicted the 1993 deficit reduction package would cause recession or stall the recovery from the 90/91 recession…” The “professional” concern was—Barro aside (and Barro, recall, is the person unhinged enough to claim that the Trump-Ryan-McConnell tax cut of 2017 would raise investment in America by as much as it increased from 1993 to 2000 and increase America’s steady-state capital-output ratio by 40%) a professional Republican, not a professional economist concern.

There had been, recall, no significant economic debate over OBRA 90.

But the rest of what Marcus has to say about fears that we may be undergoing a transition to “fiscal dominance” is good!