How Has U.S. Manufacturing Been Going Over the Past Generation?

Measure what users value in what they actually buy, rather than the numbers of boxes that leave the factory. Fix the deflators and follow things through the input-output tables summarizing the production networks and value chains, and the sector’s post‑1990 productivity story looks much brighter—and especially so in computers and electronics. But an even wider gap between those high-tech sectors and the rest of manufacturing emerges, and raises increasing puzzlement in my mind at least. Still, the slowdown is real, but it comes after the GFC, and the level attained is higher: claim of absolute “stagnation” appear to be mismeasurement…

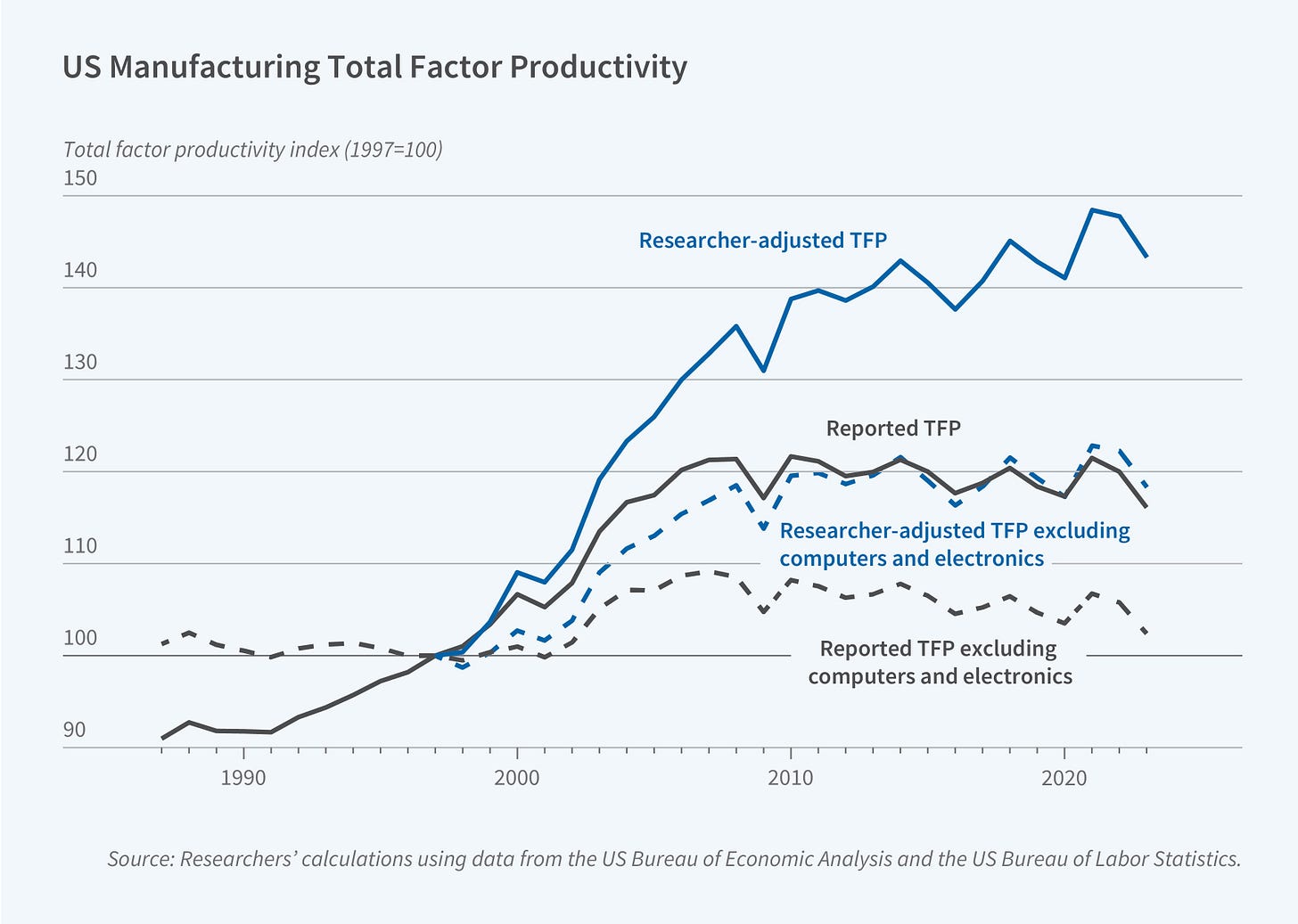

We have a very nice take on trends in manufacturing sector producrtiviy from a very strong team here:

Enghin Atalay & al.: Why Is Manufacturing Productivity Growth So Low? <https://enghinatalay.github.io/manufacturing.pdf>: ‘Nearly all measured TFP growth since 1987—and its post-2000s decline—comes from a few computer-related industries. We argue conventional measures understate manufacturing productivity growth by failing to fully capture quality improvements… [with] mismeasurement in standard industry deflators. Using an input-output framework, we estimate that TFP growth is understated by 1.7 percentage points in durable manufacturing and 0.4 percentage points in nondurable manufacturing, with no mismeasurement in nonmanufacturing industries…

…

We have long known that nearly all measured manufacturing TFP growth since 1987 comes from a few computer-related industries. But are these measurements credible? Televisions illustrate the issue: from 1997 to 2023, consumer-facing PCE prices fell at a rate of 15.4% per year, vis-à-vis 3.0% in the producer-facing indices.

Atalay, Hortaçsu, Kimmel, and Syverson calculate that, since producer-facing deflators miss quality improvements, measurements are wrong. They calculate user-facing hedonic quality adjustments to the standard deflators, and then use their input-output framework to consistently calculate estimates of TFP consistent with the different hedonic-adjusted intermediate-good quantities generated. Concretely, they replace producer‑facing deflators (PPI/import indices used in gross output) with consumer‑facing deflators from the PCE/CPI, where those show larger quality‑adjusted price declines,notably in durables, and especially computers and electronics. They then push those price-index corrections through the input–output structure to adjust both output and intermediate input prices before recomputing TFP via the dual price identity.

Thus their procedures are onceptually broader than “hedonic adjustment” alone. They undertake a system-wide revaluation of deflators consistent with production networks. The input–output structure helps separate commodity prices from margins, and allocate corrected deflators to the right NAICS commodities.

Their calculated manufacturing sector-wide TFP diverges sharply upward from official measurements after 1997, reaching about 141 by 2023, vis-à-vis 117 reported by the government. Their calculations show TFP growth understated by 1.7 percentage points in durable goods and 0.4 points in nondurables (with effectively no mismeasurement outside manufacturing). Mismeasurement is largest in computers and electronics at 5.7%-points per year, with durable goods as a whole seeing productivity growth understated by 1.6%-points per year, and nondurables by 0.5%-points per year.

However, overall manufacturing still shows a substantial slowdown after the 2007-2009 GFC, but at higher levels: growth fell from 2.2% (1997–2009) to 0.6% (2009–2023). We still have recent stagnation in manufacturing excluding computers and electronics. The difference is that the stagnation begins after the 2007-2009 GFC rather than after 1990.

I think that this is an area that researchers should crowd into. I would very much like to see people chase down: