The False Calm Before Steam: The Index H, Malthus, & the Long Slog, for Growth Was Very Real Before It Became Visible in Average Living Standards

The cliché says nothing happened before 1800. The data say capability rose steadily—only population swallowed the dividends. Replace vibes with an index: average income × √population. Suddenly, Rome, Han, and Bronze-Age workshop floors look like real steps, not “nothing.” If you think progress began with steam, you’re reading per capita and ignoring people. My index of the value of the stock of technological capability H tells a different story: slowly rising competence, finally outrunning the Devil of Malthus…

This, eighteen years old, but in my feed via a referral to a link over on a link from one of the bad social-media websites. I remember it. It struck me back then, and it still strikes me now, as not too smart:

Steven Landsburg: <https://windowsontheory.org/2025/11/04/thoughts-by-a-non-economist-on-ai-and-economics/>: ‘Modern humans… emerged about 100,000 years ago. For the next 99,800 years or so, nothing happened. Well… wars, political intrigue, the invention of agriculture—but none of that stuff had much effect on the quality of people’s lives. Almost everyone lived… just above… subsistence level… Then—just a couple of hundred years ago, maybe 10 generations—people started getting richer. And richer and richer still… at the unprecedented rate of about three quarters of a percent per year...

I remember Landsburg. Slate gave him a column for a long time—Michael Kinsley thinking he needed to spend more of Microsoft’s money on “provocative” right-wing s***posters. See: SlatePitch. The Slatepitch was never intellectual contrarianism; it was attention arbitrage. Dress up the obvious as “forbidden truth,” or varnish the indefensible as “counterintuitive genius,” and count the clicks while readers burn minutes they’ll never get back. The trick relies on a bait-and-switch: either posit a claim that violates common sense and then filibuster through rhetorical cleverness, or launder a truism as a brave revelation (“we need to admit X”). In both cases, the scarce resource—reader time—is squandered on provocation rather than illumination.

Dan Davies (2009) had a nice take on it back in the day <https://crookedtimber.org/2009/10/22/rules-for-contrarians-1-dont-whine-that-is-all/>:

Dan Davies (2009): Rules for Contrarians: 1. Don’t whine. That is all <https://crookedtimber.org/2009/10/22/rules-for-contrarians-1-dont-whine-that-is-all/>: ‘A contrarian piece properly [written]… make[s] a defensible argument which strongly resembles a controversial one…. Having done this intentionally, you don’t get to complain that people have “misinterpreted” your piece by taking you to be saying exactly what you carefully constructed the argument to look like you were saying…. A degree of diffidence is appropriate here, because the confusion is entirely and intentionally your fault…

And that applies in spades to Landsburg’s: “modern humans first emerged about 100,000 years ago. For the next 99,800 years or so, nothing happened…”

There is, today, pushback:

Ben: <[twitter.com/BenShinde...](https://twitter.com/BenShindel/status/1985842682581926039)>: ‘Ppl underestimate the technological and cultural progress between 100k ya and the rise of cities 5k ya, and again… to the… Bronze Age… classical era, and so forth….

People living in the classical era in the Mediterranean or China could publish books, travel thousands of miles and return to their homes, debate philosophy, trade luxury goods, construct large buildings, and examine their own history scientifically!

Three thousand years before that, on the Euphrates, you could build a house in a city, write letters to your family living in a distant state, write down your forecasts to track your understanding of astrology, and innovate by growing different crops to see what would sell better.

Three thousand years before THAT, you probably were an itinerant herder/farmer who knew a few hundred people in your tribal community and tried to make more durable pottery.

One step further and… you hunted and gathered and died in small bands of a few dozen. These are HUGE steps. Each of them far greater in scope and importance than the inevitable Industrial Revolution. Sam Altman, do not trust an academic that leads with this false epigraph!…

And:

Matthew Yglesias: <https://x.com/mattyglesias/status/1985846403218677979>: ‘Yeah “no growth in per capita income until the Industrial Revolution” reflects Malthusian population dynamics not a lack of technological progress—human capabilities grew steadily, which was reflected in population growth…

I would say that there are six things in play here:

The development and deployment of technologies of nature-manipulation…

The development and deployment of technologies of human productive coöperation…

The production of necessities and conveniences…

The invention and production of luxuries…

The invention and production of culture…

The development and deployment of technologies of domination…

If we are willing to make some truly heroic assumptions, we can deal with (3) and how it is supported by (1) and (2) in a manner that is at least somewhat believable.

I, in fact, have the beginnings of a catechism for all this. It is at <https://braddelong.substack.com/p/brad-delongs-history-of-economic>!:

Where do you start?

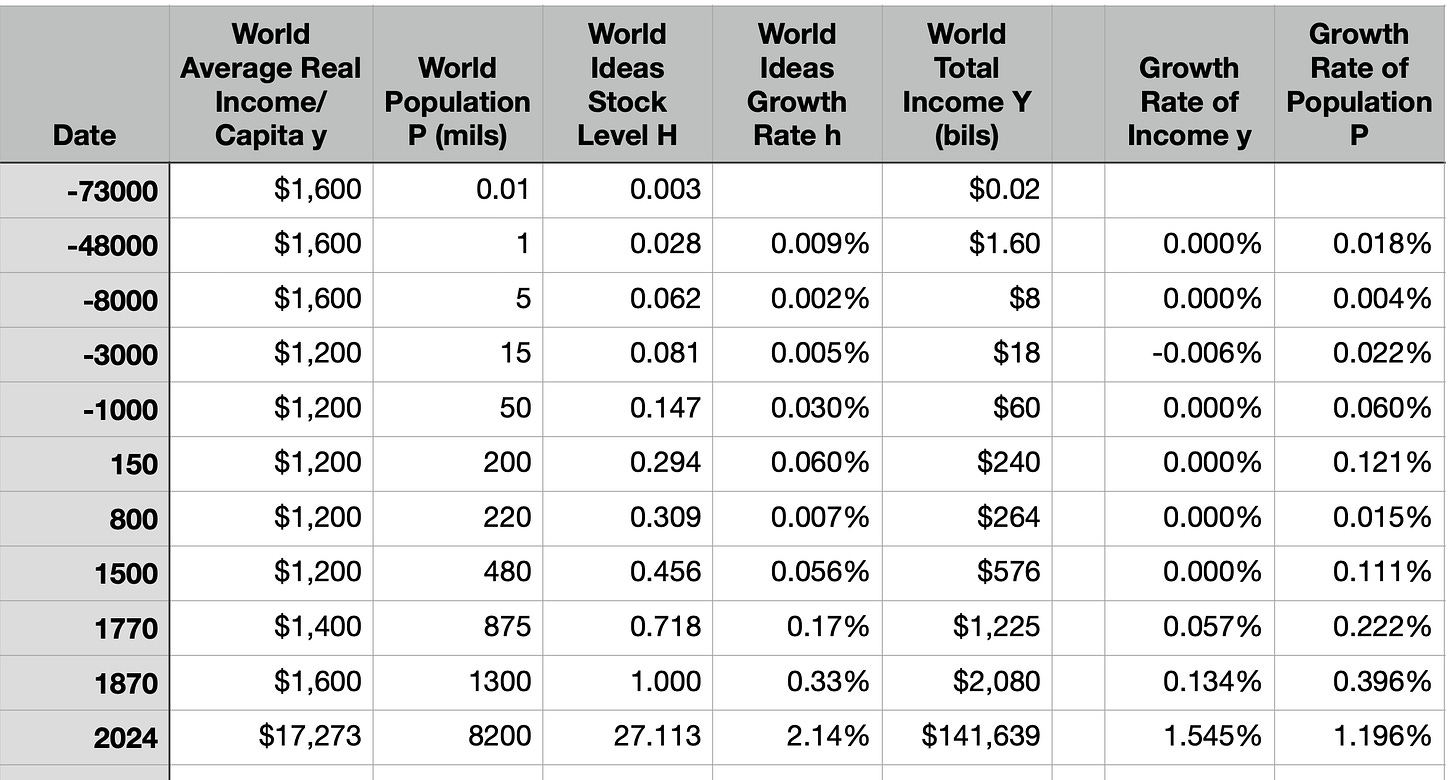

I start with a very crude global index of the value of the stock of human technology—useful ideas about manipulating nature and productively organizing humans—that have been discovered, developed, and then deployed-and-diffused throughout the world economy.

How do you construct this index?

I calculate it as the average worldwide level of income per capita, times the square root of population.

Why do you set the technology level proportional to the level of average output per capita?

That is just a normalization: it makes it easy to interpret—double the technology level, and you double the average income per capita level the world’s resources can support at a fixed population.

Why the square root of population?

The square-root recognizes that there is resource scarcity—hence generating income for more people is burdensome, and so the technology level is not simply average output per capita—but also that each mouth comes with two eyes, two arms, and a brain, so that labor is productive—hence total world product is not the technology level either. “Square-root” is a balance.

Would you die on the hill that it is square-root, rather than some other power between 0 (which gives average income per capita) or 1 (which gives total world product) multiplying population?

No. But do you have a better idea?

How about things like changing capital intensity as drivers of economic growth?

Even if Solow (1956, 1957) had not scotched that as a dominant factor, I believe that the capital intensity of the average human economy—its capital stock/annual output ratio—has been pretty close to three since shortly after the invention of agriculture. Differences in capital intensity do matter in comparing the relative prosperity levels of different societies at any point in time, but I do not see them as playing any significant role over the long term.

What do your guesses—I won’t call them numbers—then show, in terms of the annual average proportional growth rates of technology deployed-and-diffused, worldwide?

Roughly:

2.1%/yr., at least, after 1870; the Modern Economic Growth era

0.33%/yr. 1770 to 1870; the Industrial Revolution era

0.17%/yr. 1500 to 1770; the Imperial-Commercial era

0.056%/yr. 800 to 1500; the High Mediæval era

0.007%/yr. 150 to 800; the Late-Antiquity Pause era

0.060%/yr. -1000 to 150; the Axial-Iron age

0.030%/yr. -3000 to -1000; the Literacy-Bronze age

0.005%/yr. -8000 to -3000; the Early Agrarian era

0.002%/yr. -8000 to -48000; the Out of Africa-Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic eras

0.009%/yr. -73000 to -48000; the post-bottleneck African-expansion era.

Basically, growth very slow for millennia—visible only in la longue durée—then growth visible over a human lifetime, barely, after 1500; growth substantial over a human lifetime after 1770; and then growth so that humanity’s technological prowess doubles every generation after 1870.

What do your guesses show, in terms of the levels of technology deployed-and-diffused, worldwide?

Roughly:

2024: 27.1 Today

1870: 1.0, Shift to the Modern Economic Growth age

1770: 0.71 Industrial Revolution age

1500: 0.46, Imperial-Commercial age

800: 0.31, Mediæval age

150: 0.29, Classical Antiquity

-1000: 0.147, Early Iron age

-3000: 0.081, Early Literacy-Bronze age

-8000: 0.062, End of Mesolithic era

-48000: 0.028, Out-of-Africa-Paleolithic era

-73000: 0.003, Population Bottleneck

What does this measure tell us about when the big, important quantitative change in the course of human economic growth came?

It tells us that the big leap upward in economic growth—the bit watershed boundary-crossing—comes in 1870, when the global rate of technological progress jumps up more or less discontinuously from an average proportional growth rate of 0.45% per year to a rate of at least 2.1% per year.

The proportional jump from 1870 to 2020 is larger than the proportional jump from -6000 to 1870. Surely the jump from 1 to more than 20 deserves some intermediate steps?

I am playing with:

2035: Attention Info-Bio Tech Age

2000: Globalized Value Chain Neoliberal Order Age

1965: Mass Production New-Deal Order Age

1930: Morbid-Systems Interregnum

1905: Belle Époque Applied-Science Age

1870: Steampower Pseudo-Classical Semi-Liberal Order Age

1770: Imperial-Commercial Age

1500: Renaissance Global-Contact Age

800: Mediæval Age

135: High Classical Antiquity

-1000: Iron Age

-3000: Bronze-Literacy Age

-8000: Neolithic Era

-48000: Out of Africa

-73000: Population Bottleneck

with each “mode of production” marking a rough doubling of the technology level. If you believe that “the hand-mill gives you society with the feudal lord; the steam-mill, society with the industrial capitalist”, then the list above are what you would like to mark and reference: not any of this “asian-ancient-feudal-capitalist-socialist” stuff.

Do you really think that the technological-underpinning base and the corresponding superstructures of human society really stayed the same in any meaningful sense from 200 to 1500?

No. I take the point that back in the Before Times smaller quantitative changes in the level of productivity had larger qualitative effects on how societies were run—that smaller changes in the forces- and relations-of-production carried with them bigger effects on the superstructure, at least in the long run

If, before 1500 we move to dividing history up into “modes of production” by marking an age difference as a roughly √2-ing in our valuation of the stock of deployed-and-diffused “technology”:

2035: Attention Info-Bio Tech Age

2000: Globalized Value Chain Neoliberal Order Age

1965: Mass Production New-Deal Order Age

1930: Morbid-Systems Interregnum

1905: Belle Époque Applied-Science Age

1870: Steampower Pseudo-Classical Semi-Liberal Order Age

1770: Imperial-Commercial Age

1500: Renaissance Global-Contact Age

800: Mediæval Age

135: High Classical Antiquity

-1000: Iron Age

-3000: Bronze-Literacy Age

-8000: Neolithic Era

-48000: Out of Africa

-73000: Population Bottleneck

Or, in convenient tabular form:

But that still leaves us with (4), (5), (6): luxuries—which I define as things and processes you could not have possessed, utilized or experienced beforehand; cultural goods of all kinds; and then there are the negative bidders—those who do not make you offers of good things to induce coöperation, but rather make Don Vito Corleone-like offers that you cannot refuse.

And I have not yet proven smart enough to come up with even a semi-defensible way of producing even a rough quantitative guess of the value—or disvalue—of those three. But they are key to answering the original question.

No. It is not the case that nothing interesting happened.

References:

Barak, Boaz. 2025. ‘Thoughts by a Non-Economist on AI & Economics’. Windows on Theory. November 4. <https://windowsontheory.org/2025/11/04/thoughts-by-a-non-economist-on-ai-and-economics/>.

Davies, Dan. 2009. “Rules for Contrarians: 1. Don’t whine. That is all”. Crooked Timber. October 22. <https://crookedtimber.org/2009/10/22/rules-for-contrarians-1-dont-whine-that-is-all/>.

DeLong, J. Bradford. 2022. “Brad DeLong’s History of Economic Growth Catechism, Part I”. DeLong’s Grasping Reality. July 18. <https://braddelong.substack.com/p/brad-delongs-history-of-economic>.

Landsburg, Steven. 2007. “A Brief History of Economic Time”. Wall Street Journal. June 9. <https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB118134633403829656>.

Solow, Robert M. 1957. “Technical Change & the Aggregate Production Function.” Review of Economics and Statistics. 39:3 (Aug.), pp. 312–320. <https://www.jstor.org/stable/1926047>.

Solow, Robert M. 1956. “A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 70 (1): 65–94. <https://www.jstor.org/stable/1884513>.