Does Each of Us Have a Big Enough Brain to Compensate for Our Lack of Fangs, Claws, Sprinting Speed, & Dodging Quickness?

I say: “No”. Not individually we don’t. The Scarecrow in “The Wizard of Oz” had a greatly exaggerated view of what he would have been able to do if he only had a brain…

There is a shlock TV show, on the Discovery Channel, called “Naked & Afraid”.

In it, two humans are dropped into a wilderness somewhere, naked, with one and only one piece of technology each (usually something like a knife, a fire starter, or a fishing line). All around them are other mammals doing their mammal thing: living their lives, reproducing their populations, evolving to fit whatever niche they have found where they are. But the two humans dropped by themselves (well, they are surrounded by cameramen, sound technician, drivers, logistical support, and such who do not help and who stay out of the field of view) do not. Instead, the humans proceed, not too slowly, to start starving to death.

I am not being figurative or metaphorical here. Look:

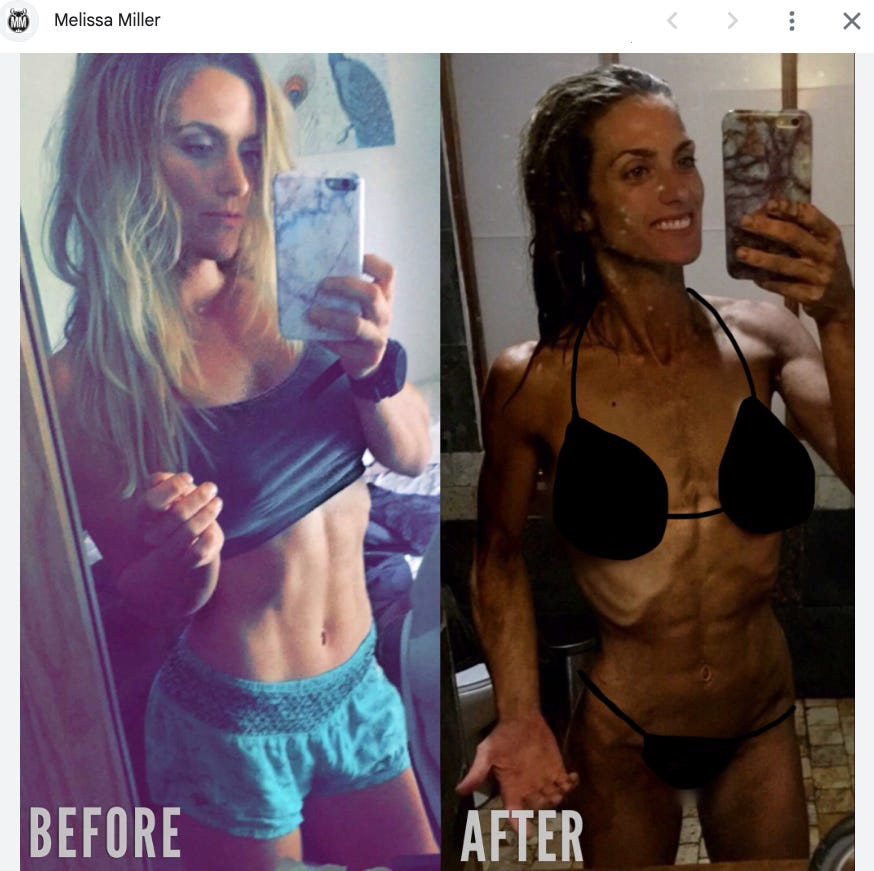

This is outdoorswoman Melissa Miller of Fenton, Michigan—Pure Michigan Melissa, Melissa Backwoods <https://melissabackwoods.com/>, across a time span of 21 days.

Melissa Miller is an expert on wilderness education and survival skills. She was dropped into the Ecuadorian Amazon with a fishing line and a partner, Chance Davis, with a knife. Over her 21 days in the jungle she lost 17 pounds: a daily metabolic deficit of about 2800 calories.

Given her likely BMR of 1500 calories, that is quite a feat.

Had she simply hunkered down and fasted, burning little energy other than her BMR, we would have expected to see a nine‑pound weight loss from burning fat. Trying to find food and avoid becoming food cost her an extra eight pounds, roughly, plus or minus.

As she described the physical stress:

Melissa Miller (2018): Naked & Afraid Weight Loss & Health Effects <https://melissabackwoods.com/naked-afraid-effects/>: ‘My hands were riddled with thorns and burn marks. We kept the fire steady the entire trip, building a mo[a]t… around it to elevate it from heavy rainfall. We also utilized a technique in which we created an oven to continually burn wet dead logs as there was no dry wood available. In order to create fire I had to construct a platform to dry out palm fibers and palm grasses for two days before I could get a tinder bundle to ignite successfully. Before that we had to ward off mosquitoes at night by covering ourselves [with] clay and mud. We prevented ants from entering our shelter area by covering the ground with thick ash from the fire…

Back in civilization, Ms. Miller needed significant medical attention, as she rapidly regained her weight, to deal with the:

fungus growing underneath fingernails and toenails.

under weight BMI.

severely infected bug bites, 4 that resulted in abscess growth, surgically extracted.

hundreds of thorns in feet and hands (result of the spiny palm trees that littered the ground in the amazon)…

Moreover, the constestants are naked, and may well be afraid, but they are not alone. In post-show interviews, they report:

On‑site medics and IVs, with medics rehydrating contestants with IV saline for severe dehydration and food poisoning.

Field safety rangers and plant ID checks, with a ~20‑person crew plus rangers on location to confirm plant identifications to prevent poisoning.

Medical tent and controlled supplies, on site, with accounts of contestants obtaining (or stealing) food/electrolytes from crew/medic areas during extreme calorie deficits.

Rapid medevac, when injuries or infections surpass on‑site care.

And Melissa Miller’s partner, Chance Davis? He lost nearly twice as much weight as she did: 32 pounds over 21 days.

A former U.S. Army Ranger, he did not have the 17 pounds of fat to lose.

And as a bigger human he had a higher BMR.

You need to burn 3 lbs. of muscle to get the caloric energy you can get from burning 1 lb. of fat. The experience of caloric deprivation without sufficient fat resources seriously messed with his head. And not just in a “in life, we have support—friends, family, podcasts, coffee, sugar—without those, you’re outside yourself; when I get hungry, I get angry” way. Instead, in this way:

The worst part was being hungry. Long-term hunger plays with your psyche. After the show, hunger made me physically reactive and angry. I carried food stashes in my pockets and car. I gained 70 pounds in a month because I couldn’t stop eating—I didn’t want to be hungry. A big scoop of peanut butter sticks in your throat; you feel full—the taste, texture, sweetness. That’s what I wanted. Creamy or crunchy? Doesn’t matter—they’re all heaven…

As I said: the experience seriously messed with his head, and made his body and brain desperate to build up fat reserves just in case something like that were going to happen again. The body and the brain had learned: even with the knife and fishing line that kept them from being completely naked, individual brains, even knowledgeable ones, are not going to be enough against the daily caloric math of the wilderness.

Meanwhile, back in the Ecuadorian Amazon, the other mammals were doing fine.

It was homo sapiens that floundered.

Recognize this: Melissa Miller is not some nature-shy city mouse. She started out as a outdoors educator and a nature-preserve naturalist, as a university-level wilderness teacher with a magna cum laude B.A. from the University of Michigan: primitive trapping, fire-making, native fishing methods, plant identification, tracking, wild foods, nature appreciation, and survival, with blades and their uses as her principal focus. The type of person who would put up YouTube videos demonstrating how to start a fire with a bow-drill, and how to catch turtles (for eating) in Michigan lakes:

Before her Amazon expedition, she would:

Melissa Miller (2018): The Prepping Guide <https://melissabackwoods.com/how-to-prepare-and-survive-naked-and-afraid-qa-with-melissa-miller/>: ‘[Be] outside all the time… reading foraging books, practicing primitive trapping, and perfecting my friction fires… trail running and road running without shoes. I would also go into the swampland and build a shelter while in a pair of shorts and a sports bra. I would sit there and let mosquitoes bite at me to understand what it might feel like living in the jungle. I had to get myself mentally prepared to feel that miserable for 21 days. I also did a lot of work outside when it would be really humid because I knew this was the type of environment I had to prepare for. I was practicing designing raised beds, and studying indigenous Amazonian tribes…. Teaching wilderness survival classes [had] also helped me prepare…. I was living and breathing “survival” as much as I could….

Letting mosquitos bite me as I trained in the woods prepared me for the mental fortitude it would take to get through (the insects play serious mind games with you out there). I also entered Ecuador with the thought that there was a possibility we m[ight] never get fire due to the humid jungle conditions. I would fast some days and shelter-build to familiarize myself with exertion through hunger…

But the principal thing Melissa Miller wished she had done differently before entering the Amazon?

Have gotten fatter.

Before she would next venture in front of the “Naked & Afraid” cameras, this time for South Africa, she put on an additional 16 fat pounds above her normal weight. She thus carried into the wilderness extra survival rations to cover her BMR energy requirements for 37 days, or to carry her for 19 days at a marathon-training pace. In her, I think accurate, judgment, there was no way for her to prepare so that she and her partners could deal with the jungle environment to be in energy balance for three weeks But she could prepare to carry three weeks’ extra energy into the wilderness so that she would be able to work hard and long while she was there.

Perhaps you just shrug your shoulders and say: “humans are relatively inept”. Even when she is at home in Fenton, Michigan, odds are she can barely remember where she left her keys last night. The other mammals out in the Amazon have been equipped by Darwin’s Daemon with teeth, claws, instincts, and brains that allow them to get into daily caloric balance. We don’t have much in the way of teeth and claws. We do have opposable thumbs. We do have big brains. They are supposed to compensate. But perhaps you shrug your shoulders and say: “they do not compensate very well”. For, out in the wilderness, Melissa Miller’s brain and thumbs failed at the one job for which Darwin’s Daemon gave them to us, for which other mammals’ teeth, claws, instincts, sprinting speed, dodging quickness, and much smaller and thus less energetically expensive brains largely suffice.

The rule: a smart, knowledgeable human (or two) in the wilderness naked should be afraid: they are highly likely to start starving to death.

And yet: Somehow we are here. We have not all yet been eaten. We have been evolved evolved. Our ancestors survived, and reproduced.

Our ancestors started to come down from the trees about seven million years ago. That was when we left the ancestors of our chimpanzee cousins still up in the forest canopy.

By five million years ago, the ardipitheci were walking upright when they had to, with much smaller and less sexually-dimorphic canines, but as of them with no signs of fire or stone‑tool use or indeed of semi-systematic butchery. Their brain cases were only 350cc, only 350 cubic centimeters. By 3.5 million years ago, the autralopitheci afarenses were habitually walking on two legs with their 450cc brain-cases. By 2.5 million years ago, the homines habiles with their Oldowan stone toolkit and 650cc brain-cases were around. And paleontologists judge they deserve our genus name: homo. By 1.8 million years ago, there were the homines erecti spreading out across the world, with their Acheulean handaxes, their endurance walking/running, and their 950cc brain-cases. When we look back 600,000 years ago, the world was then populated by the likes of the homines heidelbergenses: widely-controlled fire; complex hunting with tools like spears.

These people were not yet us: Their brain-cases were only 3/4 of the size of our brain-cases of 1350cc. They did not have organized big‑game hunting with spears, complex prepared‑core toolmaking techniques, long‑distance mobility, or evidence of our sustained and cumulative symbolic culture—cave art and engravings, personal ornaments, ritual burials, complex language‑supported planning, long‑distance exchange networks, composite tools made with adhesives, tailored clothing, or shelters. They did not have the final brain expansion, the globular skull, the reduced brow, or the chin.

And between 300,000 and 200,000 years ago there emerged people we definitely call us: homines sapientes, albeit “archaic”, with our brain-case size of 1350cc, but without the fully globular skull, the reduced brow, or the chin.

From a chimpanzee-sized brain one-quarter the size of ours five million years ago to our current state, our ancestors and then we have been evolved. And now we are here. So how can there have been so much selection pressure for larger brains when, even today, out in the wilderness they are insufficient to keep us, when naked individuals, from being hungry and afraid?

You know where I am going here. The answer of course, is simple: What is smart—what the brain is good for—is not each of our brains, but all of our brains thinking together. And the tools that we, and those who came before us, have made—tools that no one individual could make in a lifetime, and that embody all of that thinking-together one. Melissa Miller is an expert on knives, how to use them, and what to use them for. She could not make one from scratch.

From long-ago Acheulean handaxes to contemporary hunger in the Amazon, the throughline is simple: selection favored group knowledge and group production by a pecialized division of labor, not solo genius. Our edge not only was and is not claws or speed, it was and is not the ability to think up clever solutions to problems on the fly. Instead, it was pooled memory and anthology thinking-power, plus the division of labor that allows us to carve tools that contain the results of that collective thinking-power.