Policy Uncertainty Not "AI"-Automation Is Almost Surely Behind the Bulk of Recent Graduates' Job Discontent

Why are new college graduates finding it harder than usual to get a foot in the door, even as unemployment rates stay low? Do not (yet) focus on “AI”…

Whatever is making new college graduates these days think that their life is unusually difficult for their labor market segment, it is almost surely not “AI”. Amanda Mull:

Amanda Mull: What the Tough Job Market for New College Grads Says About the Economy <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-07-17/tough-job-market-for-new-college-grads-is-worrying-for-us-economy>: ‘Ernie Tedeschi… [says] hiring rates for new grads are… in line with the latter half of the 2010s…. “We still see low unemployment, and we do see pretty solid job gains,” says Allison Shrivastava, an economist at… Indeed…. But it… isn’t as lush as it was in the recent past…. [And] graduates in computer science, computer engineering and graphic design all have unemployment rates at 7% or greater…. Nathan Goldschlag… [says] the new-grad unemployment rate… “is low for things like accounting and business analytics, which… when you’re coming from the AI space… are ripe for automation”….

Stochastic uncertainty…. Companies are waiting as long as they can… in hopes of catching a glimpse of what tariffs and AI and inflation and anti-immigration policies will do to their business, which means many are delaying hiring. “Everything is just kind of stalled out and frozen,” Shrivastava says…

And Paul Krugman:

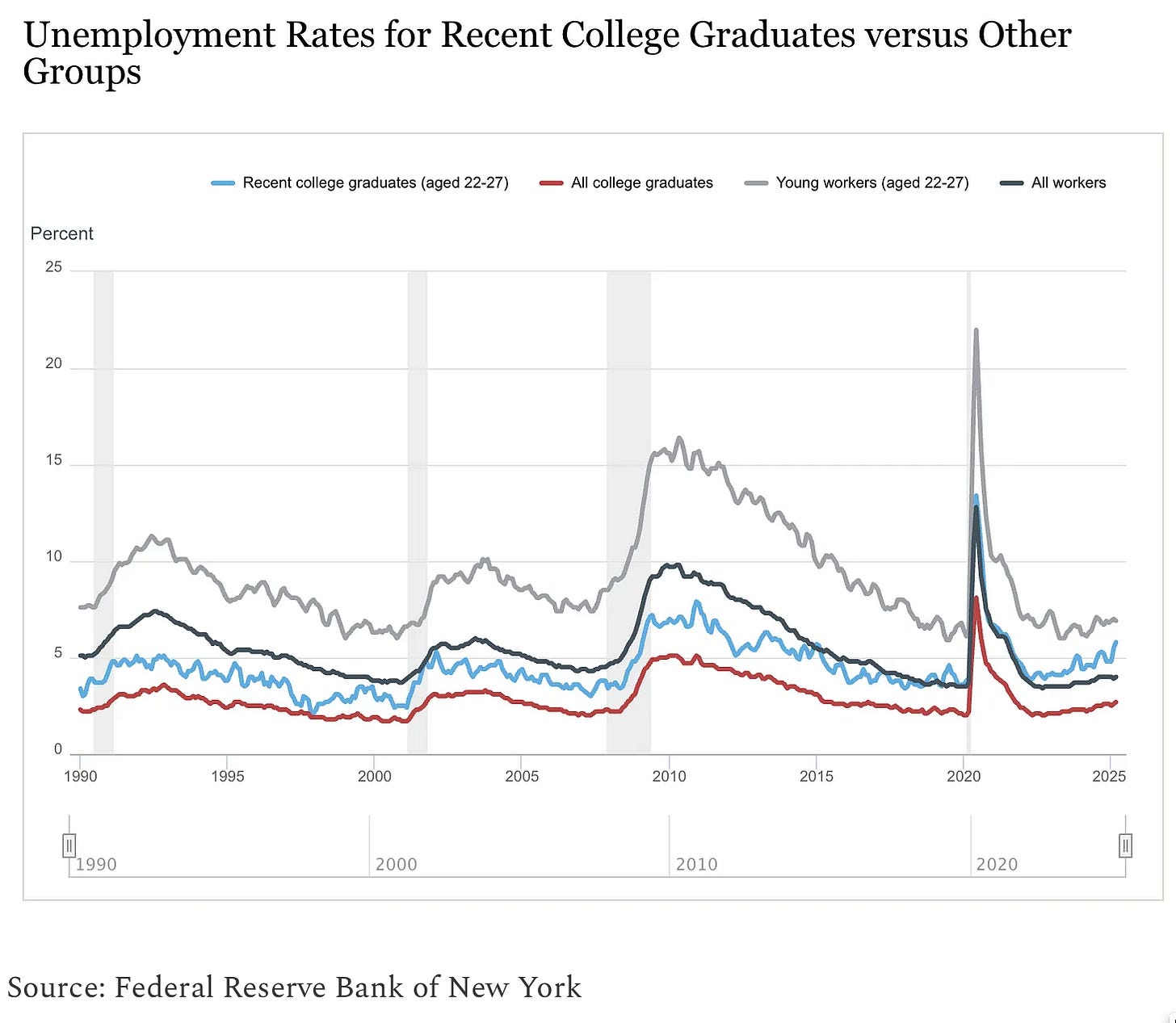

Paul Krugman: Bad Times for College Graduates <https://paulkrugman.substack.com/p/bad-times-for-college-graduates>: ‘What we’re looking at now isn’t the worst job market college graduates have ever seen. It is, however, the worst such market compared with workers in general that we’ve ever seen, by a large margin…. Young workers always have higher unemployment than workers as a group. College graduates always have lower-than-average unemployment. But normally education trumps age: Even recent college graduates have relatively low unemployment. But not now…

Although “bad” is relative, relative to other groups, to other countries, and tro previous booms only. Plus things do indeed still look very good in the health-care sector. The aging of the American population, combined with rising demand for mental health and other medical services, has kept job growth in health care robust, even now. But health care is only 1/6 of the economy.

Derek Thompson <https://www.theatlantic.com/economy/archive/2025/04/job-market-youth/682641/?gift=o6MjJQpusU9ebnFuymVdsJ1qwI70CnAkjDXBfrYqvHw> reports that the gap between total and recent-grad unemployment went from 3%-points in the depressed economy of 2012 down to 1%-point in the mid-2010s, which was markedly lower than the 1.75%-points typical of the 1990s. The gap went negative even before the plague. From 2014 to 2024, with zigs and zags, it fell from +1%-point to -1% point—a fall of 0.2%-points per year—before rapidly falling to nearly -2%-points today.

In tech, it actually may well be “AI”, or at least have an “AI” component,.

Tech has the most “AI” true believers by far. There are tech bosses saying, but we do not really knwo how representative they are, that workers should see this year whether ChatGPT instantiations can be their interns. Why pay for a junior analyst to draft reports or summarize documents when a large language model can do it in seconds? But similar fears have accompanied every wave of technological change, from the spreadsheet’s arrival in the 1980s (which, some predicted, would eliminate the need for accountants) to the earlier automation of switchboard operators and typists in the mid-20th century. The reality is that while some tasks are indeed automated away, new roles and new forms of work tend to emerge, though not always at the same pace or for the same people.

More important, probably, is that money that would go to new hires is instead going to buying NVIDIA chips. In the current tech boom, companies are pouring vast sums into the hardware that powers artificial intelligence—most notably, the high-performance graphics processing units (GPUs) produced by NVIDIA. These chips are the backbone of machine learning and generative AI, and demand has been so intense that NVIDIA briefly became the world’s most valuable company. For firms, the calculus is straightforward: Investing in AI infrastructure is seen as a ticket to future competitiveness, while hiring junior staff is a cost that can be postponed. The opportunity cost, however, is that young people seeking a first job may find doors closed—not because their skills are obsolete, but because capital is being allocated elsewhere. For a college freshman, this is a reminder that macroeconomic trends and corporate priorities—often far removed from undergraduate coursework—can shape the contours of the job market in unpredictable ways.

Thus there is still now hard and not even a semi-convincing soft narrative that “AI is to blame” for entry-level job scarcity. It seems to be almost surely, still, merely a convenient scapegoat. It is tempting, especially for the media and for anxious graduates, to pin the blame for a tough job market on the rise of artificial intelligence. After all, stories about robots taking jobs are both dramatic and easy to understand.

But hiring slowdowns are driven by broader forces: economic uncertainty, shifts in business investment, and the cyclical ebb and flow of demand. Blaming AI allows both policymakers and business leaders to avoid grappling with deeper, structural issues—such as the mismatch between what colleges teach and what employers need, or the long-term stagnation in productivity growth that has made firms more cautious about expanding payrolls, or short run policy uncertainty.

It is here that you want to place your bets on what is going on: Policy uncertainty—over trade, immigration, inflation, and technology—is driving the short-run piece of the jobs cycle. It has paralyzed business planning, reinforcing a cycle of hiring freezes and risk aversion that hits new entrants hardest. When companies face an unpredictable policy environment—say, uncertain tariffs on imported goods, shifting rules about work visas, or volatile inflation—they tend to delay major decisions, including hiring. A tech firm unsure whether it will be able to recruit international talent may postpone expanding its junior staff. Similarly, a manufacturing company facing the threat of new tariffs might hold off on bringing in new graduates until the dust settles. This risk aversion is particularly damaging for those at the start of their careers, who rely on a steady flow of entry-level openings to get a foot in the door.

The deeper sclerosis is this: risk aversion among both employers and workers, leading to fewer opportunities for mobility and advancement. In a healthy labor market, people change jobs frequently, chasing better pay or more interesting work, and employers are willing to take risks on new hires. Today, by contrast, both sides are playing it safe. Workers are staying put, afraid that if they quit, they won’t find something better—a sentiment reflected in historically low quit rates. Employers, meanwhile, are reluctant to hire or promote, preferring to “wait and see” rather than invest in untested talent. This mutual caution creates a feedback loop: With fewer people moving, fewer positions open up, and the market becomes stagnant. Job-change rates are abnormally low on both accessions and separations. “Just get your foot in the door” is much less effective when doors are not opening as quickly or as widely.

For the longer-run, the rise in the college wage premium is over, and a decline has (probably) begun. For decades, earning a college degree was a reliable ticket to higher earnings, as the labor market rewarded those with advanced skills and credentials. But in recent years, this “college wage premium”—the extra money earned by graduates compared to non-graduates—has plateaued and may even be falling. The reasons are complex: The supply of degree holders has grown faster than the demand for high-skill jobs, and technological change has not produced a corresponding surge in new, well-paying roles for graduates. The value of a degree is still strongly positive. But it is no longer increasing.

Plus: Today, the dominant corporate ethos is flexibility: Firms prefer to hire for specific needs, often on a temporary or contract basis, and are less willing to invest in employee development. This shift is driven by competitive pressures, shareholder demands, and the rise of management philosophies that prioritize efficiency over loyalty. For students entering the workforce, this means that career ladders have become career lattices—less predictable, more fragmented, and requiring more self-direction and networking to climb.

Bottom line: Unemployment is low overall. New college graduate unemployment is not high. But, compared to others, America’s newest graduates are finding it relatively harder to find jobs than they ever have before. Blame corporate reluctance to invest in talent, the start of what may be a long-term shift away from steady rising wage premiums for college degree-holders, and—likely most important—unprecedented policy volatility, and thus unusual risk.

That means weaknesses in young workers’ educational pedigrees are likely to shadow them throughout their careers. Those who start out behind—whether because of a less prestigious college, a lower GPA, or fewer internships—will find it especially difficult to catch up or leapfrog, even as their actual skills improve over time.

So pay attention in junior high school algebra, kids!