Cattle, Social Cohesion, Culture, Civic Cohesion, Collective Uplift, & Civilization in Sub-Saharan Africa; Causality; & the TseTse Fly

Marcella Alsan’s bioculturalsociogeographical take on long-run African economic development: why the story is radically incomplete without the tsetse fly: one insect and the fate of a continent, for it looks like the most important player in Africa’s economic history wasn’t a king or a conqueror, but a bloodsucking fly…

Nick Decker reminds me of the great Marcella Alsan’s job market paper of a decade and a half ago. How the tsetse fly, by killing cattle and stymieing plow agriculture, set the stage for centuries of institutional divergence: a lack of plows and of centralized states leading to the peculiar vulnerabilities of its societies to modes of imperial-colonial exploitation.

Her thesis is fully persuasive. And yet it is part of a pattern of very good articles that together I find somewhat problematic, for history can only be truly causally explained once.

Nick Decker <https://x.com/captgouda24/status/1937388725299781764>: ‘Why was Africa so empty, and for so long?… Marcella Alsan argues that it was the TseTse fly which did it, by rendering vast swathes of land uninhabitable. It is not the direct effect of sleeping sickness which matters, terrible though it is, but how it kills livestock. The wild game of Africa is immune, but it is absolutely murderous to cattle. Without cattle, you can have no plow. You have no dung to fertilize crops. You have no carts or wheels, or even packhorses—you must rely upon human portage. Without carts, there are no roads. In short, productivity tanks and centralization is impossible…. The Bantu migration was recent, and they abandoned crops and animals when they crossedh terrain unsuited for them…. She finds truly enormous effects….

In particular, it increases the incidence of slavery, an institution which is incredibly toxic to sustained economic growth. Without livestock, the value of humans goes up, and without cities, they can’t run. What might Africa have been like without the fly? We already know — there would have been states, just as there was in Ethiopia and Great Zimbabwe. It is little surprise that those ethnic groups which perform the best today are those which have had the longest exposure to centralization, states, and reading. It would not surprise me if their descendants are still afflicted by the environment thousands of years hence. An incredible paper…

Not “uninhabitable” for people, but uninhabitable for oxen, and oxen being an absolutely key factor in the web of biotechnology throughout all of the non-rice lands of Eurasia-Africa.

People began to herd domesticated cattle in Africa in large numbers starting around the year -5000. Remember: back then the Sahara was very different than it is today. It was in no sense a barrier. Crossing it was in no sense arduous. Then was the African Humid Period, when rainfall was much higher, monsoon patterns were stronger, and the region supported a rich array of wildlife, as well as human communities. Instead of the vast, arid desert we know today, it was a landscape of lakes, rivers, grasslands, and scattered woodlands—a true “Green Sahara.”

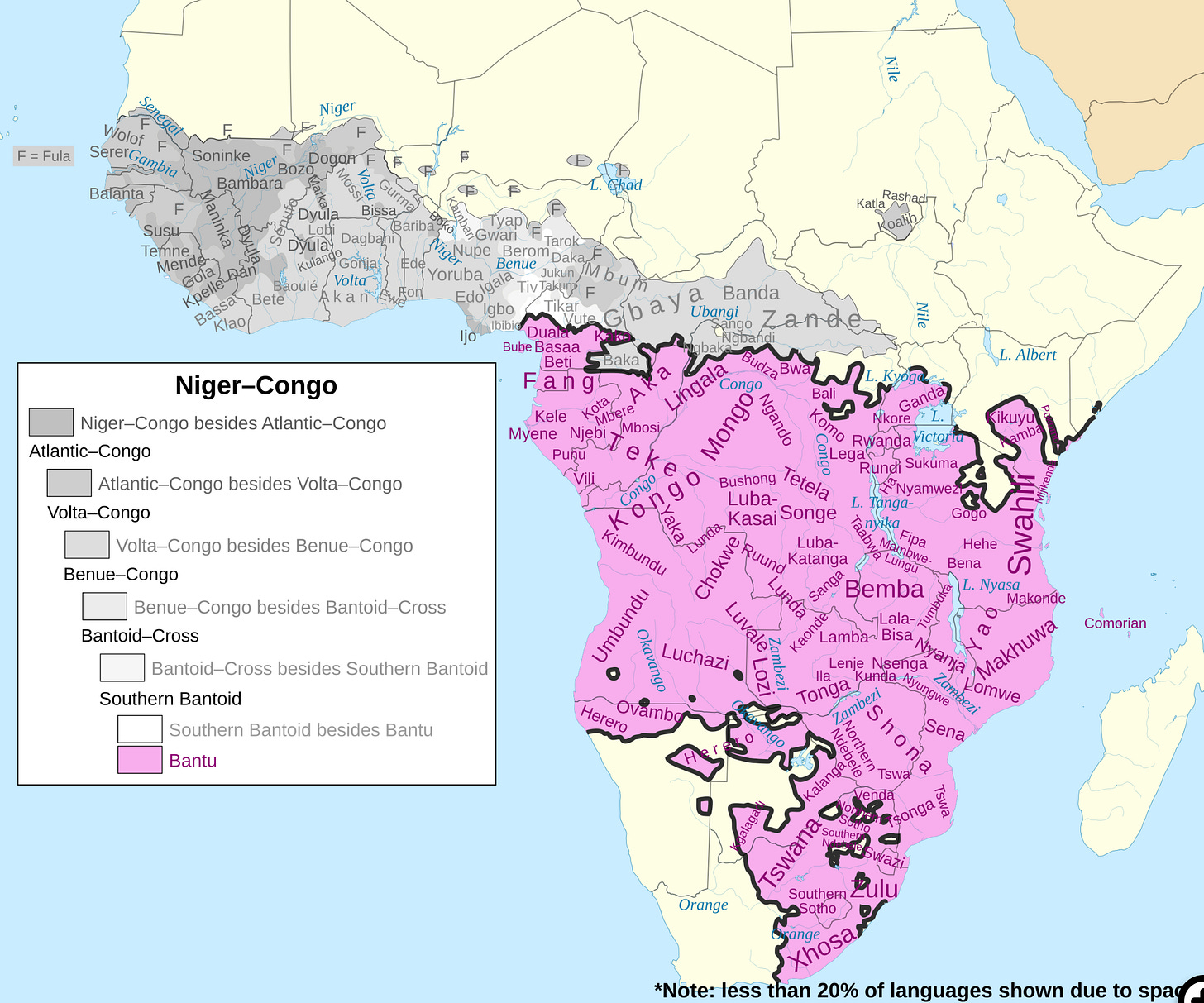

As of the year -1500, in Africa, we find substantial numbers of oxen and ox-cultures north of the tsetse fly belt, but not south. We find oxen no longer in the Sahara, which is now too dry, but along its northern and southern edges, in the Nile Valley, and in the Ethiopian highlands. Then the Iron Age, along with the yam and the oil palm. comes to the Bantu population around the Benue River Valley, in the borderlands of southeastern Nigeria and western Cameroon. And the Bantu expansion follows: not a conquest, or, rather, not just a conquest. We see a slow, multi-century process of migration, adaptation, and cultural diffusion, radiating out from this heartland. As Bantu-speaking peoples moved, they carried with them not just language, but a package of agricultural and technological innovations that allowed them to thrive in new environments—except, of course, where the tsetse fly or dense rainforest posed insurmountable barriers to their lifeways:

With newly-bread somewhat trypanotolerant cattle like the N’Dama in West Africa, and following the “green highway” that was the Lake Victoria-Tanganyika-Malawi corridor, they made their way through the highlands along the west edge of the rainforest into the Zambezi-Limpopo-high veldt corridor, bringing culture, technology, and cattle all he way down to the Cape of Good Hope

And so we get to Marcella Alsan’s results using bioecological climatic suitability of a region to the tsetse fly as her instrumental variable. Her TseTse Suitability Index (TS) predicts significant, detrimental effects on development only within Africa. Outside Africa, the same index has no explanatory power. And a one standard-deviation increase in the TSI is associated with:

a 22%-point decrease in the likelihood that an African ethnic group had large domesticated animals.

a 9 %-point decrease in intensive cultivation (i.e., less use of land-saving, labor-intensive farming).

a 7%-point decrease in plow use.

a 19.5%-point increase in the probability that females performed the majority of agricultural tasks.

a 12%-point increase in the likelihood an ethnic group used slaves.

an 8%-point decrease in the probability an ethnic group was politically centralized.

A one standard deviation increase in TSI is associated with

a 28% decrease in intensive farming.

a 46% reduction in population density in 1700.

Her simulations of Africa without the tsetse fly generate a continent with only half as much indigenous slavery, and nearly double the pre-colonial population. Plus the TSI has a negative correlation with current economic performance that is robust to including colonizer-legal origin effects.

What do I think of this?