LECTURE NOTES: Lash, Cash, & Cotton in the Imperial-Commercial & Early SteamPower Age

& the racialization of slavery. A ten-mintue taste of what my lectures have to say about post-1500 slavery. This then becomes the lecture introduction when I give the longer lecture…

Why post-1500 did the world’s wealthiest societies outsource brutality? And how did they come to create the idea of race and use it as their rationalization. Let us move from ancient misfortune to modern ideology, tracing slavery’s transformation as merchant and then industrial capitalism rlse. And we will pause for a moment to note the unseen costs of cheap goods: how the middle class became more than complicit but rather the prime mover in Atlantic slavery’s global machinery.

Start here: Whenever and wherever something is valuable, two strategies for acquiring it inevitably emerge. The first is what I might call the “nice economist” approach: resources are used to purchase the desired good or asset, transferring ownership through mutually agreed exchange. This method avoids destruction, minimizes waste, and—at least in theory—leaves all parties better off. It is, as Adam Smith would have it, the invisible hand at its most benevolent.

But there is always a second, darker option: the use of coercion, violence, or outright theft. When a prosperous mercantile or industrial economy sits at the center of a wider system—think of Britain in the 19th century, or Athens in the 5th century BCE—its very demand for resources creates perverse incentives at the periphery. Those on the outside, unable to compete with the core’s purchasing power, may instead turn to force. Thugs with spears—or, later, guns and whips—find profit in seizing people and land, compelling labor to produce goods for export to the wealthy center.

This pattern is ancient. In the 5th century BCE, the Skythian and other horse-lord elites of the Black Sea region enslaved local populations to grow wheat, which was then shipped to feed the citizens of Hellas, especially the city of the Athenai. Fast forward to the 19th century: the industrial economies of Britain and the U.S. North depended on cotton produced in the American South. After the forced “removal’ of Native Americans, the land was abundant but labor was scarce and valuable—hence, the brutal expansion of slavery.

Slavery, in any form, is a moral abomination. Within the household, and on the small farm or in the small workshop, it is moderated by the fact that the slave master has to look the enslaved person in the eye. In some cases, it is not that much worse than the “normal” household domination lineage heads exercise over poor, third cousins who have no independent resources of their own, but even there the fact that the point of buying a slave is that they are an alien without social power, a social network, or the ability to form one, making it sharper and nastier as they are easier to exploit, and to exploit more completely.

As the scale of the slave enterprise grows, and as the household becomes embedded in a merchant-capitalist sector where the slaves work is not limited by what the household can utilize, but is rather unlimited because their work can be sold on the market for money, things get worse. And the human social practice of slavery reaches its most monstrous proportions on large plantations, where enslaved people are forced to produce cash crops for distant markets. Especially absentee plantations. Owners then never need to become within eyesight of what they have set in motion. They never face any of the brutal human cost of their profits. Instead, they simply write terse letters to overseers: “Why are my returns not higher? Why have you not squeezed more wealth from this enterprise?” And what kind of person can flourish in such an intermediate overseeing position, and so becomes an overseer?

The system is then designed for maximum extraction, minimum accountability, and a studied indifference to suffering—a pattern that, I regret to say, recurs over and over throughout human—or, rather, inhuman—economic history.

After 1500, merchant capitalism became not just a sector in an agrarian-age economy, but rather the predominant mode of organization in what rapidly became imperial-commercial society. And so the typical mode of slavery underwent a profound transformation. It became plantation, and thus truly, obscenely nasty. And it became racialized in a way it had not been before.

In earlier eras, slavery was largely a matter of misfortune—being captured in war, falling into debt, or simply being in the wrong place at the wrong time. The enslaved were, for the most part, still recognized as people, albeit people in an unfortunate legal and social position. Yes, Aristotle famously mused that some non-Hellenes were actually “slaves by nature”. This, however, was more a rhetorical flourish than a dominant ideology. Slavery fit into a broader hierarchical order, where your place—slave or free—was simply your lot, not your essence, and where there were many hierarchical gradations in some Great Chain of Being.

However, as agrarian-age societies were followed by less ascriptive, more mobile-contractual societies—ones where individuals were supposed to find their own place through markets and negotiation and the construction of social networks—this old logic of slavery as a low status into which you were fixed by birth or ill-luck became harder to sustain. The world increasingly committed, at least in rhetoric, to individuals’ both getting to choose and having to find their place. The result was the valorization of individual freedom and equality.

So what then could you do with the idea of slavery?

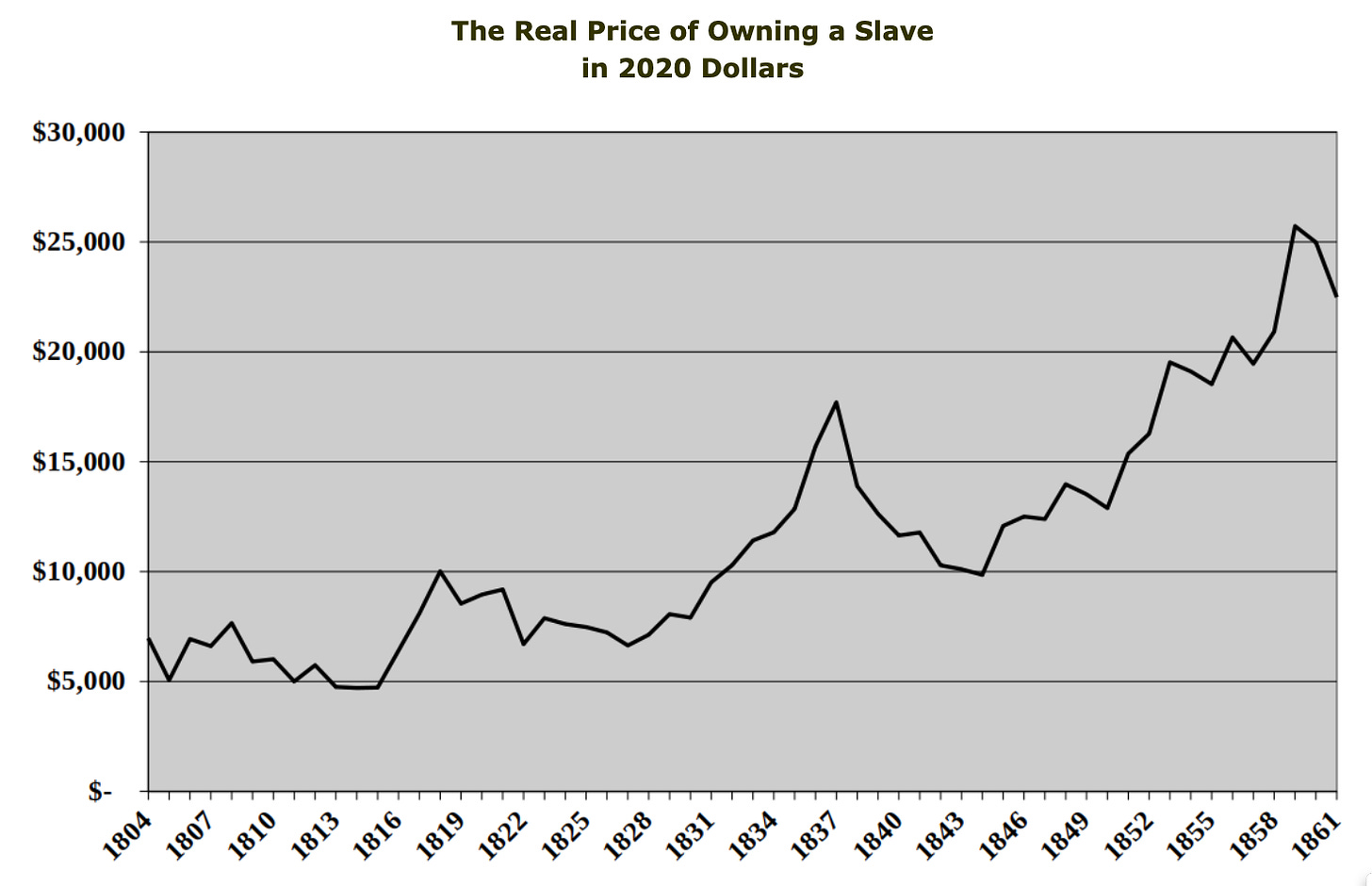

You could eliminate it. And eventually the British Empire led the way to doing so. But it was very, very profitable! It was increasingly profitable as the commercial transoceanic economy gathered strength! Its profitability was amped-up another order of magnitude by the coming of SteamPower society. And so societies doubled down on the idea that rights, freedom, and equality were only for the true, full humans. They began to focus on a belief that some groups were inherently suited to enslavement in order to justify the continued existence of slavery within an Enlightenment-era world of humans with natural rights.

And race became the marker: Africans and their descendants were cast as “slaves by nature,” their status justified not by circumstance but by supposedly immutable characteristics. This was the ideological sleight of hand that underpinned the Atlantic slave trade and the plantation economies of the New World.

It is crucial to remember, though, that the principal beneficiaries of this system were not the plantation owners. The principal beneficiaries were the middle-class consumers at the heart of the industrial and commercial economies. Their cheap sugar, cotton, and tobacco were made possible by the brutal labor of enslaved people on distant plantations. This is the uncomfortable arithmetic of global capitalism: prosperity in one place, purchased at the cost of suffering in another.

Yet, history is not without its ironies.

The American Civil War (1861–1865) saw the states of the United States that did not secede and formed the Union volunteer to pay a staggering price to end slavery: 400,000 young men killed, another 300,000 maimed.

The magnitude of the suffering he had set in motion drove Abe Lincoln mad. As he said in his Second Inaugural Address, it appeared possible—even likely—that the war would continue until:

all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword…

Yet he had still done a good thing in the eyes of God to have refused to allow the Confederates to secede from the United States, and preserve for a while their institution of slavery. For:

as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether’…

The American Civil War. 400,000 Union young men dead. Another 300,000 maimed. To rescue 5,000,000 American slaves from complete bondage. But, then, because of the substantial failure of Reconstruction, return them to a form of caste serfdom in which they had little property, less voice, and no vote. For a century. And as Claudia Goldin has pointed out, even setting aside this immense human cost, the United States wasted so much treasure on the war that, by her calculations, it could have used it to more than purchase every enslaved person in the United States at peak 1860 market prices, and also provided each freed family with 40 acres of decent farmland, plus a mule or two. Plus 300,000 Confederate young men dead, and 250,000 maimed.

Yet, still, well done by good and faithful servants, in our eyes, and hopefully in the eyes or others wiser than me.

Time to sum up, provocatively:

Slavery was not always about race—until the coöccurence of modern capitalism with Englightenment ideas demanded a new justification for old cruelties. The middle-class comforts of the nineteenth century rested on a foundation of violence and forced labor, rationalized by a newly invented ideology of race. The economic engine of empire pressured the turning of something that had been seen as random misfortune into a natural and systemic racial hierarchy, all in service of cheap cotton and sugar. What linked the Skythian horselords north of the Black Sea in the -400s to the cotton fields of Mississippi in the 1800s? The relentless logic of the plantation and the market linked them. And in the American case, the bill, grimly, came due with bloody justice of a strange and peculiar sort in the Civil War.

If reading this gets you Value Above Replacement, then become a free subscriber to this newsletter. And forward it! And if your VAR from this newsletter is in the three digits or more each year, please become a paid subscriber! I am trying to make you readers—and myself—smarter. Please tell me if I succeed, or how I fail…