Brad Setser Says Smart Things on Exorbitant Privilege Unearned & Earned

How global capital still bets on America, and what could break the spell. Private capital, not central banks, have caused and bankrolled America’s current-account deficits over the past decade, and promise to continue to do so—until trust or returns falter. The dollar’s dominance is less a birthright than a daily wager on American institutions, markets, and myth. It is domestic political decay, not rival currencies, that pose the gravest threat to the dollar’s global reign…

Passing 50,000 total subscribers sale, for two days only:

The next such deal will have to wait until this newsletter passes 100,000…

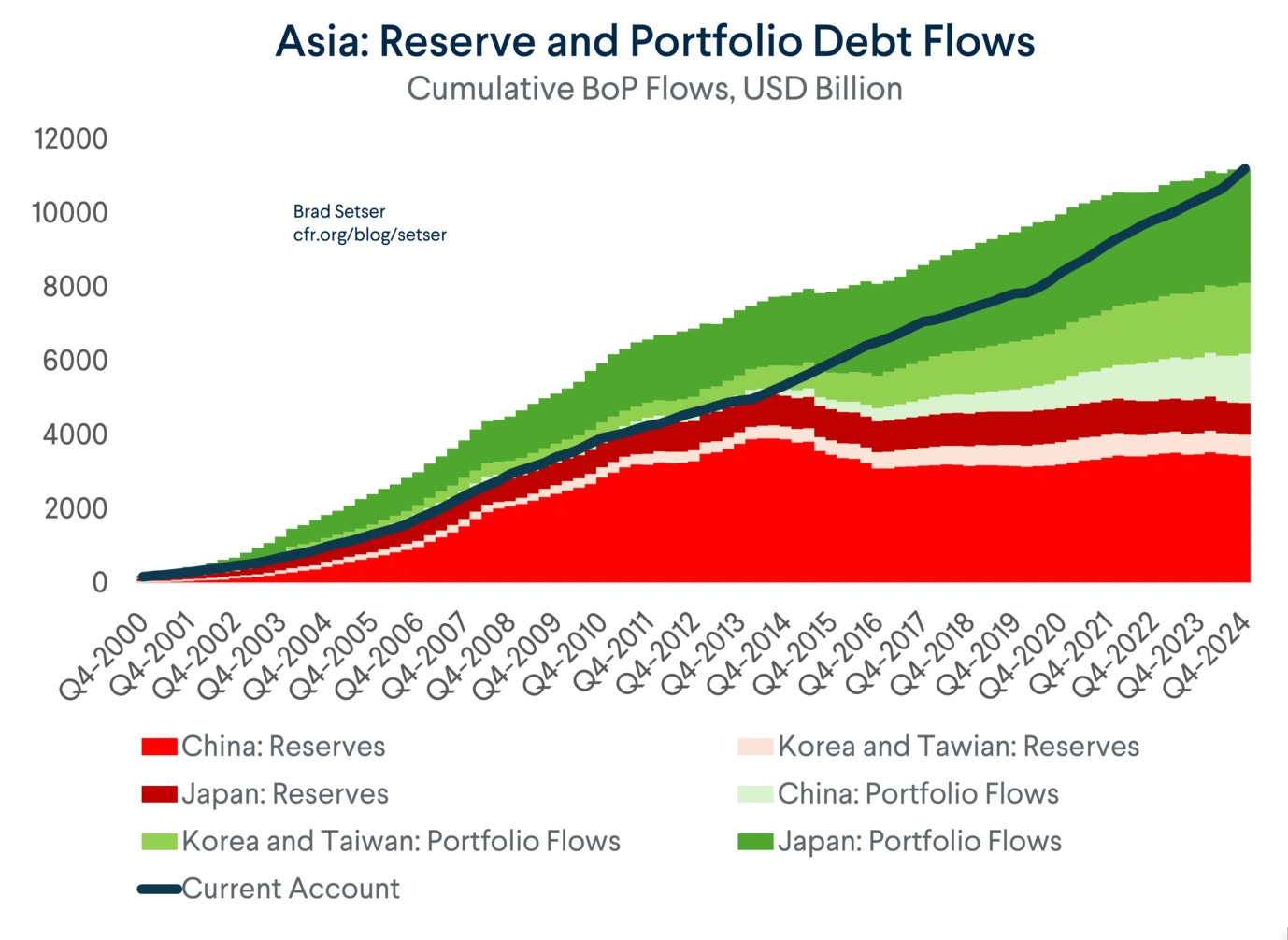

The dollar’s status is not a law of nature but a fragile, continuously renegotiated contract. Over the past decade, private capital inflows driven by risk, return, and faith in American institutions have supplemented the old régime of official reserve accumulation that began with the East Asian financial crisis of 1997-1998 and George W. Bush’s 2001 greenlighting of China’s joining the WTO. Thus we need to focus on what keeps the world’s capital flowing into the United States, financing deficits that would topple lesser nations and keeping the dollar aloft. The answer these day lies less in the oft-invoked “exorbitant privilege” reserve-currency status of the dollar, but in a far more contingent, and fragile, set of expectations about American returns and reliability. The era when official reserve accumulation explained the bulk of U.S. capital inflows ended in 2014. Since then, it is has been private investors—hungry for yield, shelter, and a stake in the technological furnace of the Second Gilded Age—who have kept the dollar aloft and the capital inflow coming.

Thus I 100% endorse the extremely sharp Brad Setser when he writes:

Brad Setser: The Dollar’s Global Role and the Financing of the US External Deficit <https://www.cfr.org/blog/dollars-global-role-and-financing-us-external-deficit>: ‘There is too much talk about the dollar's role as a reserve currency, and too little talk about expectations of exceptional returns. Reserve accumulation hasn't driven the financing of the US current account deficit in recent years….

Actual data… shows that the flow into dollar assets in the last few years has largely come from private investors seeking yield, not state investors who are compelled to hold safe assets…. Reserves tracked the current account surplus almost perfectly until 2014, but have subsequently fallen well short. Portfolio outflows have made up the gap.… And if the analysis is extended to Europe, the same conclusion holds…. The U.S. exceptionalism argument… sometimes gets rolled together with the… dollar… [as]… “reserve currency flow”… [which,] in theory, [is] not a function of returns; the U.S. exceptionalism argument is directly tied to financial returns…

Brad Setser Is Smart

This pushback against often lazy shorthand tropes of economic punditry is very welcome.

It does need to be stressed that the U.S. has gained its large negative global cumulative capital account position in part because or its exorbitant structural privilege as the world’s reserve currency, but in most part not. It does need to be stressed that that cumulative capital account position is because the world’s rich expect investments in the United States to do something very important for them: preserve, protect, and substantially grow their wealth. They still see the U.S. as a (relative) safe haven for the financial property even of non-citizens, and still see investments in the U.S. as a way of participating in the immense profits from being in the furnace where the future is being forged in our Second Gilded Age.

Yet I do not expect Brad Setser’s real numbers to have much effect. I expect to continue to read, mostly, the same narrative. I expect the Economist-level narratives of the U.S. current account deficit to continue cloaked in the "exorbitant privilege" argument: America spends more than it earns, and foreign governments are content to finance that habit by pouring money into U.S. Treasuries and other safe dollar assets as reserves, and this happens because the U.S. dollar is the world’s reserve currency and because foreign governments do not want to see their currencies undergo large appreciations in value.

But as Setser points out, since about 2014, this framework has cracked. Foreign governments have not had to face the “buy dollar reserve assets or watch our export competitiveness sharply decline” choice. Central banks are no longer the main dollar financiers. Instead, it’s been private investors.

Returns or Risk?

But why have private investors been doing what they have been doing? There are at least two intertwined forces behind the $8 trillion-plus in cumulative portfolio inflows into the United States over the last decade: return and risk.

U.S. equities, especially tech platforms, have delivered extraordinary returns, especially when denominated in other currencies. The dollar has been strong. Plus, for much of the period, bond returns have been not high but rather superior to elsewhere. Interest rates—even if very low by historical standards—offered a better deal than the alternatives in Europe or Japan.

Thus the United States offered financial assets that were not only deep and liquid but also unusually profitable.

But there is also risk. I keep thinking that this may be a more profound effect. I keep looking for ways to assess it. I keep coming up short.

Here is the idea. The United States remains the only country in the world where nearly everyone rich would not be unhappy to place their money. This holds even those who fear the United States. And this holds even for those who see the United States in relative decline. Have enough American partners who make large enough campaign contributions to senators, and your money in the U.S. is safe.Whether it is the billionaire flying into LAX on a Lear Jet or the oligarch's cousin arriving via a coyote and a rubber boat, the U.S. legal and financial system remains insurance—not just against inflation or depreciation, but against capricious autocracy, kleptocracy, and the systemic chaos of states elsewhere, where rule of law is at best aspirational.

Consider also the intergenerational angle: global elites are not just seeking return or refuge for themselves, but for their heirs and heiresses. If the great-grandchildren of the world’s rich plan to live in Los Angeles or New York, then buying dollar assets is part of family planning, not just portfolio management.

All of these seem to me highly likely to give the inflows a surprising durability—but only so long as the U.S. remains the preferred future.

Thus forecasting is very complicated.

If flows are driven by return, they can and will reverse. All it takes is better returns elsewhere and an end to return-chasing.

But if flows are driven by risk insurance—if the dollar is the least bad umbrella under which to shelter your wealth from the world’s storms—then they are sticky, and might even rise as global uncertainty increases.

Possible Fragility Beneath the Surface

To the extent the U.S. benefits from these flows because it is seen as a relatively stable, law-governed, opportunity-rich society, then domestic political and institutional rot—TRUMPXIT, judicial delegitimization, governance gridlock—may pose a bigger long-term threat than any rival currency.

Break the U.S. legal umbrella, and the insurance motive collapses. Should the likes of Lutnick, Bessent, Miran, or Trump manage to delegitimize the legal or financial scaffolding, the U.S. would not simply lose its reserve-currency status. It would experience a private-sector sudden stop—and these are always messy. Think Asia 1997 or Argentina, but scaled to the size of the U.S. current account deficit.

Plus, if the flows are driven by return, the risks are also acute. Returns are volatile. Tech platform oligopolists will find their positions eroding. AI and crypto booms fade. Bubbles do burst. A sharp correction could turn a rush-in into a rush-out. And once outflows start, the dollar could weaken, interest rates could spike, and the “safe haven” reserve currency status might itself look more like a mirage.

Global Demand for U.S. Assets

On top of this, the traditional reserve-currency story does have considerable force. It does matter that the U.S. is the only place in the world where you can park hundreds of billions of dollars in safe, liquid assets without moving the market. It matters that global trade is still invoiced in dollars. And it matters that emerging markets can be expected to build dollar reserves—not to earn yield, but to insure against financial crises and protect their currencies—as they grow.

But this backstop is not enough. A generation ago, scholars like Obstfeld and Rogoff worried about dollar-denominated liabilities and global imbalances. Those concerns were real—but the true blow came from elsewhere: housing, viruses, and political decay.

Yet the old risks haven’t gone away.

Looking at the world now and comparing it to the world of 2025, they have not even shrunk. They have grown into something larger, and more complex.

Privilege Largely Earned Earned, But Still Fragile

Setser is right. The dollar’s status is not simply structural; it is earned, daily, through return and reassurance. But privilege can become complacency. A reserve currency must be undergirded by a trustworthy legal system, a resilient financial structure, a credible commitment to rule-bound governance, a government focused on providing high-externality public investments in education, infrastructure, and technology; and a private economy focused on entrepreneurship and info-tech and bio-tech sectors growth rather than oligopolistic platform-tech attention-harvesting market position. We are moving into the attention info bio tech age, with the first of these largely zero-sum, and only the second and third capable of producing win-win growth and its associated returns.

Erode these—law, finance, state competence, state capacity, competition, and entrepreneurship—and the dollar’s exceptional role may begin to look less like a privilege, and more like a bubble.

And bubbles, as history teaches us, eventually burst.

References

Eichengreen, Barry. 2011. Exorbitant Privilege: The Rise and Fall of the Dollar and the Future of the International Monetary System. Oxford: Oxford University Press. <https://archive.org/details/exorbitantprivil0000eich>.

Forbes, Kristin J. 2010. “Why do foreigners invest in the United States?” Journal of International Economics 80(1): 3–21. <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2009.09.001>.

Gourinchas, Pierre-Olivier, & Hélène Rey. 2007. “From World Banker to World Venture Capitalist: US External Adjustment and the Exorbitant Privilege.” In G7 Current Account Imbalances: Sustainability and Adjustment, edited by Richard Clarida, 11–55. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. <https://www.nber.org/chapters/c0121.pdf>.

Habib, Maurizio Michael. 2010. “Excess returns on net foreign assets – the exorbitant privilege from a global perspective.” European Central Bank Working Paper Series, No. 1158. <https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp1158.pdf>.

Mann, Catherine L. 1999. “On the Causes of the US Current Account Deficit.” Peterson Institute for International Economics. <https://www.piie.com/commentary/speeches-papers/causes-us-current-account-deficit>.

Obstfeld, Maurice, & Kenneth Rogoff. 2009. “Global Imbalances and the Financial Crisis: Products of Common Causes.” Asia Economic Policy Conference, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. <https://eml.berkeley.edu/~obstfeld/santabarbara.pdf>.

Setser, Brad W. 2025. “The Dollar’s Global Role and the Financing of the US External Deficit.” Council on Foreign Relations, June 8. <https://www.cfr.org/blog/dollars-global-role-and-financing-us-external-deficit>.

Triffin, Robert. 1960. Gold and the Dollar Crisis: The Future of Convertibility. New Haven: Yale University Press. <https://archive.org/details/golddollarcrisi00trif>.