Think of It as Generating Our "Investment Surplus", Not as Our "Trade Deficit"

Yes, America's reserve-currency rôle in the world economy is very much worth working hard to keep...

READING: PROJECT SYNDICATE: Barry Eichengreen: "Sterling’s Past & the Dollar’s Future". His column, and my notes...

One has factual and analytical disagreements with my office neighbor Barry Eichengreen at one’s grave intellectual peril.

But here I have one.

Barry says that in then-Chancellor of the Exchequer Winston Churchill’s 1925 decision to return the British pound sterling to the gold standard at its pre-WWI nominal parity, one important contributing factor was that “the most articulate opponent [of the return to the pre-WWI nominal sterling peg], John Maynard Keynes, had an off night when given an opportunity to make his case to the chancellor…”

I do not think that we really know this.

Our source for this is Churchill’s private secretary P.J. Grigg. As I wrote in the notes to Slouching Towards Utopia: “P.J. Grigg, Churchill’s Private Secretary at the Exchequer, claimed that Keynes’s arguments at the dinner were unconvincing…. Then again, Grigg’s hostility towards Keynes was so great that he would have been unable to recognize strong arguments had they been made, He did write on the very first page of his memoirs: ‘I distrust utterly those economists who have with great but deplorable ingenuity taught that it is not only possible but praiseworthy for a whole country to live beyond its means on its wits, and who, in Mr. Shaw’s description, teach that it is possible to make a community rich by calling a penny tuppence, in short who have sought to make economics into a vade mecum for political spivs…’” That is aimed directly at Keynes, and well captures Grigg’s total contempt for the man.

But, other than that complaint about what is essentially a single throw-away line in the piece below, I have no complaints.

I do have some comments, however, at the end.

Meanwhile, read the whol thing:

Barry J. Eichengreen: Sterling’s Past & the Dollar’s Future <https://www.project-syndicate.org/onpoint/the-us-dollar-s-fall-from-grace>: ‘Apr 10, 2025: US President Donald Trump says he wants to preserve the dollar's international role as a reserve and payment currency. If that's true, the history of pound sterling suggests he should be promoting financial stability, limiting the use of tariffs, and strengthening America's geopolitical alliances.

TOKYO – In April 1925, a hundred years ago this month, Winston Churchill, in his capacity as chancellor of the exchequer, took the fateful decision to return pound sterling to the gold standard at the prewar rate of exchange.

Churchill then, not unlike US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent now, was torn between two objectives. On one hand, he wanted to maintain sterling’s position as the key currency around which the international monetary system revolved, and preserve London’s status as the leading international financial center. On the other hand, he, or at least influential voices around him, saw merit in a more competitive – read “devalued” – exchange rate that might boost British manufacturing and exports.

Why Churchill chose the first course is uncertain. The weight of history – British economic preeminence under the gold standard prior to World War I – pointed to restoring the monetary status quo ante. The City of London, meaning the financial sector, lobbied for a return to the prewar exchange rate against gold and the dollar. The most articulate opponent, John Maynard Keynes, had an off night when given an opportunity to make his case to the chancellor.

The effects were much as predicted. Sterling regained its position as a key international currency, and the City its position as a financial center. Now, however, they had to contend with New York and the dollar, which had gained importance, owing to disruptions to Europe from the war and the establishment of the Federal Reserve System to backstop US financial markets.

Also as predicted, British exports stagnated. At current prices, they were lower in 1928-29 than in 1924-25, when the decision to stabilize the exchange rate was taken.

Here, clearly, a strong pound and the high interest rates required to defend its exchange rate were unhelpful. But to attribute the British economy’s poor performance entirely to the exchange rate is to jump to conclusions.

For one thing, the export industries on which Britain traditionally relied – textiles, steel, and shipbuilding – were now subject to intense competition from later industrializers with more modern facilities, including the United States and Japan. The situation was not unlike the competition currently felt by US manufacturing from China and other emerging markets. Then as now, it is not clear that a weaker exchange rate would have made much difference, given the emergence of these rising powers. Nor did the tariffs the United Kingdom imposed in the 1930s revive its old industries.

Moreover, Britain had difficulty developing the new industries that constituted the technological frontier – electrical engineering, motor vehicles, and household consumer durables – even after devaluing the pound in 1931. The US and other countries were quicker to adopt new technologies and production methods, such as the assembly line. Union militancy discouraged investment. Workers with the relevant skills and work ethic were in short supply. Again, these are not unlike complaints heard today from the operators of TSMC’s new semiconductor fab in Arizona or Samsung’s chipmaking plants in Texas.

And, of course, it did not help that the 1930s were marked by trade wars and a decade-long depression.

Notwithstanding these problems, sterling’s position as an international currency survived the 1930s. In fact, the pound regained some of the ground as a reserve and payments currency that it lost to the dollar in the preceding decades. Whereas Britain was broadly successful in maintaining banking and financial stability, the US suffered three debilitating banking and financial crises. The UK maintained stable trade relations with its Commonwealth and Empire under a system of imperial preference that negated the effects of otherwise restrictive tariffs. And it remained on good terms with trade partners and political allies beyond the Commonwealth and Empire, including in Scandinavia, the Middle East, and the Baltics, where monetary authorities continued to peg their countries’ currencies to sterling.

The lessons for those seeking to preserve the dollar’s status as a global currency are clear:

Avoid financial instability, which in the current context means not allowing problems in the crypto sphere to spill over to the rest of the banking and financial system.

Limit recourse to tariffs, since the dollar’s wide international use derives in substantial part from America’s trade relations with the rest of the world.

And preserve the country’s geopolitical alliances, since it is America’s alliance partners who are most likely to see the US as a reliable steward of their foreign assets and hold its currency as a show of good faith.

The US, to all appearances, is going down the opposite path, risking financial stability, imposing tariffs willy-nilly, and antagonizing its alliance partners. What was achieved over a long period could be demolished in the blink of an eye – or with the stroke of a president’s pen. Churchill was aware of the risks. As he put it, “To build may have to be the slow and laborious task of years. To destroy can be the thoughtless act of a single day”…

However, while I have no complaints, I do have additions:

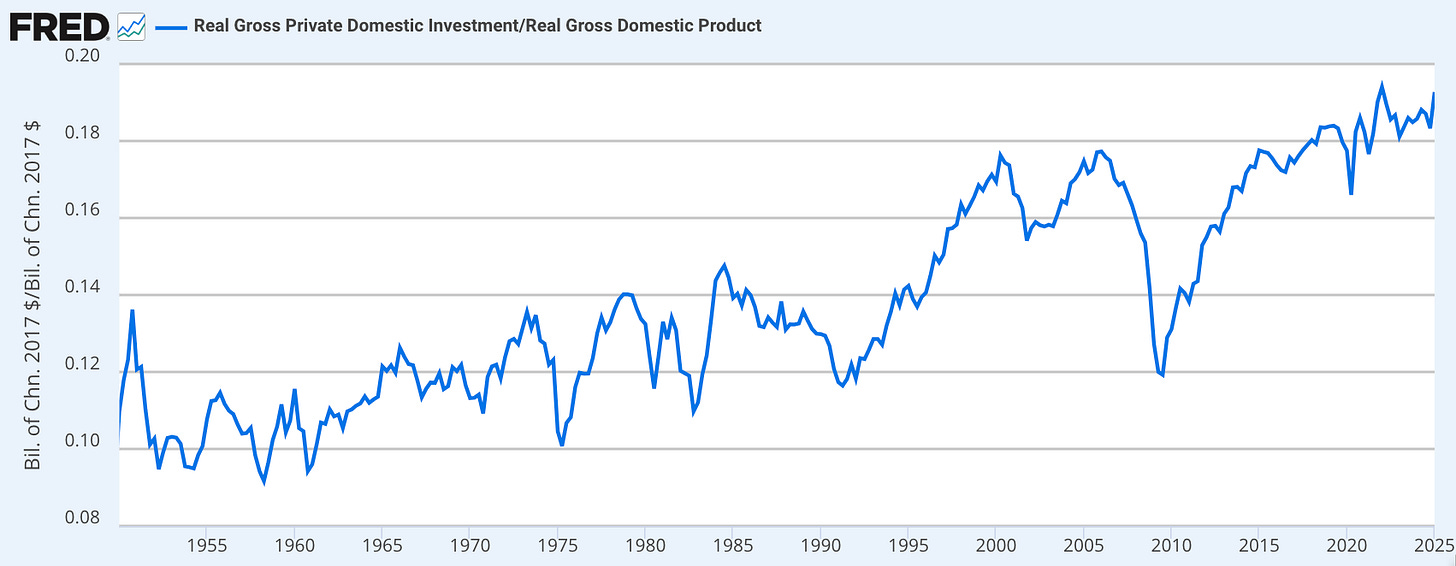

As people have been noodging me in email, it would be much better framing for those of us who want to keep the dollar's exorbitant privilege to focus discussion not on America's "trade deficit" but on its "investment surplus":

Too often, discussions about the U.S. trade balance are framed in alarmist tones: the trade deficit is presented as a sign of economic weakness, of deindustrialization, or of financial imprudence. But this is an aspect of the bag-of-words nature of language, and of the English language in particular. “Deficit” sounds weak and bad. “Surplus” sounds strong and good. However…

Current-account rade deficit = capital-account investment surplus by arithmetic necessity:

From an accounting standpoint, the trade deficit is the mirror image of an investment surplus. Dollars that foreigners earn from exporting to the U.S. are recycled into dollar-denominated assets—from Treasury securities to direct investment in U.S. businesses. These capital inflows keep interest rates low, support the dollar's value, and finance productive investment. Thus a country’s current-account trade deficit is the surplus of national investment over national saving.. These two sides of the ledger must match. Is a trade deficit a problem? Perhaps. But is there any reason to think that eliminating an investment surplus would not be a bigger problem?

If the market were perfect—which it is not—at the margin these considerations would offset each other:

A perfect market would have already pushed the economy to the point where at the margin the benefits from an additional dollar of investment surplus were exactly offset by the opportunity cost of not running a reduced dollar of trade deficit. Global production and investment would have already flowed to wherever they were most productive.

In such a world, the size of a country’s trade deficit or investment surplus would reflect the optimal allocation of global capital.

However, of course, the real world is not this tidy. Capital does not always flow to its most productive uses. There are frictions, informational asymmetries, institutional weaknesses, and policy distortions.

We must focus on those and on the balance among them if we are to think coherently.

Which, I note, absolutely nobody anywhere in the Trump administration is doing, or shows even the slightest sign of being capable of trying to do, if any of them wanted to, which none of them do.

So the key questions in deciding whether one wants the government to put its thumb on the balance here is: What, where, and how important are the externalities?:

The way economists set up the world, you need an “externality”—a cost or benefit not already captured in the market price—to justify any “interference” with the competitive market system. In the context of the trade balance, externalities might arise from the erosion of the industrial capacity to develop and deploy valuable technologies that arises as a consequence of a trade deficit. The right debate to have, then, is not whether the trade deficit is arithmetically equal to the investment surplus (it is). The right debate to have is whether the social costs of the former are greater than the social benefits of the latter. This is a question about the structure of technological ecosystems.

The big negative externality from a trade deficit springs from the erosion of the communities of engineering practice that enable the creation and deployment of product and process technologies:

When industries shrink or disappear due to import competition, the damage is not only in lost output or employment. There is also the loss of accumulated tacit knowledge, of organizational capabilities, and of the embedded skills of networks of suppliers, workers, and engineers. These are the communities of practice that are essential for maintaining and advancing a country’s technological frontier. Their decay can have long-term effects on innovation and productivity.

On the other hand, the big positive externalities from the investment surplus induced by the dollar's strong role as safe haven are two:

The first is the rent-sharing of gains from investment to stakeholders in the production, distribution network other than the investors. These are mighty.

The second is the fact that not just production but investment nurtures communities of engineering practice as well. Capital inflows into the U.S. fund productive investment in new technologies, in infrastructure, and in the kinds of high-tech and knowledge-intensive industries that are America’s comparative advantage.

These investments can generate and sustain engineering communities just as much as manufacturing can. Moreover, the global demand for dollar assets gives the U.S. a unique position: it can earn seigniorage, attract talent, and spread its economic influence widely.

Thus a country’s position as the linchpin of the global financial system is not analogous to the "resource curse". The problem with having a compared to advantage in natural resources is threefold: (a) the communities of engineering practice are elsewhere, and the knowledge externalities from their creation and maintenance (mostly) benefit those elsewhere and not you; (b) the slopes of supply and demand in the global economy make technological progress in producing natural resources primarily benefit resource consumers (which technological progress in producing manufactures primarily benefits manufacturing producers); and (c) your politics is poisoned by high-stakes zero-sum fights over resource rents. To compare the dollar’s role to a “resource curse” is one of the dumbest lights on the tree of economic ideas.

Indeed, one interpretation—the very sharp Bob Allen’—of America’s economic-industrial exceptionalism in the 1900s is that it grew out of the scale of the investment build-out of America in the late 1800s:

A build-out at a scale that Germany and Britain could not match

A build-out that induced by our open-borders policy and the resulting high rate of immigration of the entrepreneurial.

Economic historian Bob Allen has, I think, pushed this hardest. In his view, America’s economic preëminence throughout the entire 1900s century was not just a result of technological ingenuity or abundant resources. It was also about scale—about being able to mobilize vast amounts of capital and labor in a relatively open and entrepreneurial environment. Immigration brought skills, ambition, and diversity. The financial system mobilized capital on a national scale. And the government often played a facilitating role in this build-out. These elements combined to create a dynamic and resilient industrial economy.

People also refer to income-distribution externalities from a reduced trade deficit—that a smaller trade deficit would mean more good blue-collar jobs at good wages:

Yes, trade deficits can contribute to wage stagnation and job losses in certain sectors. This has distributional consequences. If import competition undermines well-paying jobs for workers without a college degree, the result is social dislocation and political backlash.

That said: That was true four decades ago. It is not true now.

The structure of the U.S. labor market has changed. The bulk of good blue-collar jobs at good wages that were destroyed were destroyed by deunionization. The bulk of the remainder that were destroyed were destroyed by labor-saving technological progress in the supply of manufactures faster than growth in the demand for manufactures. Yes, there was a “China shock”. No, there was not any such thing as a “NAFTA shock”. The blue-collar jobs we could get from import substitution are not good jobs, they are not especially at good wages, and they are few in number. to imports in the 1990s and 2000s are not coming back, and those that remain often do not pay as well or offer the same security. Today, the challenge is as much about automation, changing technology, and internal institutional arrangements as it is about trade. Focusing on the trade deficit alone, without understanding these broader forces, is to misdiagnose the problem.

Of course, Barry did not have space to make any of these additional points:

Barry Eichengreen’s piece is a nice example of high-class economic history and policy analysis. That he did not delve into these issues is not a fault, but a choice about scope and emphasis.

Perhaps I should try to compress these points, and use them for my own now-overdue Project Syndicate column this month?:

Yes, I think I should.

Selected References:

Allen, Robert C. 2014. “American Exceptionalism as a Problem in Global History.” The Journal of Economic History 74 (2): 295–317. <https://doi.org/10.1017/S002205071400028X>.

Grigg, P. J. 1948. Prejudice and Judgment. London: Jonathan Cape.

Eichengreen, Barry. 2025. “The US Dollar’s Fall from Grace.” Project Syndicate, May 14, 2025. <https://www.project-syndicate.org/onpoint/the-us-dollar-s-fall-from-grace>.

Appendix:

Here is Grigg’s full description of the debate, at which Keynes may or may not have had an off-day:

P.J. Grigg: Prejudice & Judgment: ‘Perhaps the most important problem which faced Winston [Churchill] in the first year of his Chancellor[ of the Exchequer]ship was whether or not this country should return to the Gold Standard.

The legend has grown up and has obtained such currency that Winston himself has almost come to believe it, that the decision to go back to gold was the greatest mistake of his life, and that he was bounced into it in his green and early days by an unholy conspiracy between the officials of the Treasury and the Bank of England. Nothing could be further from the truth. He was certainly told soon after his arrival that the Act under which gold payments were suspended would expire with the year 1925, and that he would, therefore, have to face before very long the choice between going back to gold or legislating to stay off it for another period of years. It is also the case that the Treasury and the Bank were definitely in favour of taking the final step in the continuous process of restoring the pound to parity, which had been going on ever since the first World War ended.

Here it may be as well to observe that, between the report of the Cunliffe Committee in 1918, recommending an ultimate return to gold at the old figure, and lateish in 1923 when Keynes first began to cast faint doubts on this policy, not a dissenting voice was heard. During the immediate post-war inflation, the pound had fallen to $3.20. In 1920, Austen Chamberlain had taken drastic steps to balance the Budget and arrest the inflation. The counter-measures naturally involved adjustments of wages and a considerable amount of unemployment. The unemployment was intensified by the coal strike of 1921, and at its highest point it reached a figure of about two millions. By April 1921 the era of rapid reductions in Bank Rate had begun, and by July 1922 it was down to 3 per cent, in those days regarded as a very low figure. Sterling on New York had recovered to $4.20 by January Ist, 1922, and for the whole of that year, English prices were practically stable.

The exchange at the beginning of 1923 was $4.634, unemployment was still nearly at 1,500,000, but it diminished steadily to round about 1,100,000 by December. In the second six months, prices began to rise and so, in July, Bank Rate was raised to 4 per cent. The pound had got as high as $4.734 in February 1923 but from that point it declined to $4.34. In 1923 prices rose sharply but, oddly enough, unemployment increased somewhat, while from the time the Dawes Report was published in April, the exchange rose again, and by the beginning of 1925 was once more within 24 per cent of its pre-war parity. Some contemporary calculations seemed to indicate that at this figure, sterling was over-valued by something under 5 per cent. But even so, it looked as if the last step towards the goal ought to be neither long nor difficult.

Since the Armistice in 1918, every Government, including Mr. MacDonald’s, had proclaimed its intention of working towards the restoration of the Gold Standard as soon as possible, and the course of fiscal and monetary events in these years was plainly being continuously directed to this end. It will be remembered, also, that the famous Genoa Resolutions, for which R. G. Hawtrey and the late Sir Henry Strakosch were largely responsible, urged a general return to gold among the nations of the world, though not in all, or evem in a majority of the cases, at the previous parities. In fact it can be said that, when Mr. Baldwin became Prime Minister for the second time, the opponents of the policy advocated by the Cunliffe Committee were confined to a small number of those who were susceptible to the still small voice of Keynes, and this in spite of the fact that the still small voice was already beginning to be immeasurably amplified by the multiple organ of Lord Beaverbrook.

Mr. Churchill reaffirmed the policy on February 12th, 1925. In March, Bank Rate was advanced to 5 per cent, which, to those who had eyes to see, meant that a decision had been taken. But there was no question of its having been a snap decision. The examination was careful and exhaustive. In Winston’s private circle there were a few of the Keynes-cum-Beaverbrook school who vehemently put the case for not returning to gold at all, there were others who pressed him to wait, and others again who advocated a return but at a somewhat lower gold equivalent than the one which had prevailed in 1914. All the points made by the enemies or critics were put to his official advisers, and argued out at length in written memoranda and oral discussions. Nor did his advisers ever conceal from him that a decision to return might involve adjustments which would be painful, and that it would certainly entail a more rigorous standard of public finance than any system of letting the exchanges go wherever the exigencies of a valetudinarian economic and financial policy took them.

I remember well his giving a dinner at which I was present, where there was to be a sort of Brains Trust on the subject. The proponents of a return to gold were Sir Otto Niemeyer of the Treasury and Lord Bradbury as he had now become, while the antagonists were Keynes and Mr. McKenna. The symposium lasted till midnight or after. I thought at the time that the ayes had it. Keynes’s thesis, which was supported in every particular by McKenna, was that the discrepancy between American and British prices was not 2% per cent as the exchanges indicated, but 10 per cent. If we went back to gold at the old parity we should therefore have to deflate domestic prices by something of that order. This meant unemployment and downward adjustments of wages and prolonged strikes in some of the heavy industries, at the end of which it would be found that these industries had undergone a permanent contraction. It was much better, therefore, to try to keep domestic prices and nominal wage rates stable and allow the exchanges to fluctuate.

Bradbury made a great point of the fact that the Gold Standard was knave-proof. It could not be rigged for political or even more unworthy reasons. It would prevent our living in a fool’s paradise of false prosperity, and would ensure our keeping on a competitive basis in our export business, not by allowing what I believe the economists call the ‘terms of trade’ to go against us over the whole field, but by a reduction of costs in particular industries. In short, to anticipate a phrase which Winston afterwards used in answering a sneer about our having shackled ourselves to gold, we should be doing no more than shackling ourselves to reality.

To the suggestion that we should return to gold but at a lower parity, Bradbury’s answer was that we were so near the old parity that it was silly to create a shock to confidence and to endanger our international reputation for so small and so ephemeral an easement. It was very likely that contractions of the basic industries would have to be faced, but having lost the advantage of the flying start which we gained at the time of the Industrial Revolution, we should have to do something of the sort anyhow, and the best future for this country, therefore, lay in preserving and even developing our international banking, insurance and shipping position, and in turning ourselves more and more into producers of the higher classes of goods, in whose manufacture individual skill and workmanship was of greater moment than the employment of large numbers of operatives at repetitive processes—in other words, in those forms of enterprise where the man was more important than the machine.

Looking back at this argument, it seems to me to embody all that conflict between the long and the short view and of the general and the particular, which Mr. Henry Hazlitt of the New York Times asserts in his amusing book Economics in One Lesson to be the essence of the cleavage between the classical economists and their modern successors. Certainly Keynes was a man of changing, if not of short, views. For example, in about 1923, 1 remember his writing that ‘we must cling to Free Trade as an immutable dogma’. In 1930 and 1931 he was advocating a general tariff of 10 per cent to correct the initial over-valuation of sterling which he appeared to believe had persisted ever since 1925. Of course he would have preferred to devalue sterling by 10 per cent, assuming that it would have been possible to slip quietly off one parity and settle down quickly at one 10 per cent lower. But he calculated that Mr. Snowden would never willingly agree to this and so he fell back on something which was in flat contradiction to his immutable dogma of 1923.

Needless to say, the high protectionists of the Tory party welcomed this notable new ally and loudly trumpeted his conversion. And in 1931 and 1932 they got their way, but it was not a uniform 10 per cent revenue tariff; there was a wide measure of industrial protection as well. Very soon after, they got agricultural quotas in addition.

In the meantime, of course, Britain had gone off gold, not in a genteel way, stopping short at a devaluation of 10 per cent, but with a catastrophic fall of 30 per cent or more which destroyed whatever basis of coherence and stability the world had at that time.

One thing about this argument comes back to me with crystal clearness. Having listened to the gloomy prognostications of Keynes and McKenna, Winston turned to the latter and said: ‘But this isn’t entirely an economic matter; it is a political decision, for it involves proclaiming that we cannot, for the time being at any rate, complete the undertaking which we all acclaimed as necessary in 1918, and introducing legislation accordingly. You have been a politician; indeed you have been Chancellor of the Exchequer. Given the situation as it is, what decision would you take.’

McKenna’s reply — and I am prepared to swear to the sense of it — was: “There is no escape; you have got to go back; but it will be hell.” I am confirmed in my recollection of McKenna’s attitude by reading again his speech at the annual meeting of the shareholders of the Midland Bank on January 28th, 1925. In this, he Janus-like praises the skill of those who had been managing the currency without the Gold Standard to help them, while at the same time sagely announcing that ‘as long as nine out of ten ‘people think the Gold Standard is the best, then it is the best’. The Times took this utterance as favouring an early return to gold. And in the debates in the House, not one responsible member proclaimed himself an enemy of the Gold Standard. The Labour Party wanted to be in a position to say ‘I told you so’ if things went wrong, and put down a formal resolution deploring the undue precipitancy of the step the Chancellor of the Exchequer was taking; but at no stage did they divide against the Gold Standard Bill or any of its provisions.

Others who afterwards became strident critics of the Gold Standard imitated this interesting example of having it both ways. Snowden moved the Labour motion, but it is easy to discern, even from the dead pages of Hansard, how little his heart was in it, which was not surprising, seeing how often he had committed himself to the policy of the Cunliffe Committee. Moreover, he had, in the previous June, set up a secret committee, consisting of Austen Chamberlain, Bradbury, Niemeyer, Mr. Gaspard Farrar and Professor Pigou, which was, in effect, to advise when and how the final step in that policy should be taken. The committee did not report till after he had left office. It recommended almost exactly the procedure which his successor adopted.

Winston’s speeches on the subject were extremely effective, and I still find in them an entirely valid defence of the action which he then took, and which he seems subsequently to have been persuaded to repent. Some of his metaphors were apt as well as picturesque and amusing. I have already mentioned the one about shackling ourselves to reality. Others which make me chuckle to this day are his confession that ‘we could no doubt keep our export trade continuously booming at a loss’; his comparison of those who wanted to go back at a reduced parity to grocers or tailors who in difficulties ‘take an ounce off the pound’ or ‘snip an inch off the yard’; and, best of all, his assertion that what the followers of Keynes wanted was to establish a quicksilver standard.

Incidentally, Keynes wrote in the Nation that the Treasury and the Bank of England had contrived to arrange the return of gold along the most prudent lines open to them. There could be no doubt, he went on, of our ability to maintain the Gold Standard once the decision was made. The critics had opposed the policy of returning to it because it was unwise, not because it was impracticable. It is to be noted that in 1925 Sir Henry Strakosch was an enthusiastic and public supporter of everything that had been done…