Think of It as Generating Our "Investment Surplus", Not as Our "Trade Deficit"

Yes, America’s reserve-currency rôle in the world economy is very much worth working hard to keep…

READING: PROJECT SYNDICATE: Barry Eichengreen: “Sterling’s Past & the Dollar’s Future”. His column, and my notes…

One has factual and analytical disagreements with my office neighbor Barry Eichengreen at one’s grave intellectual peril.

But here I have one.

Barry says that in then-Chancellor of the Exchequer Winston Churchill’s 1925 decision to return the British pound sterling to the gold standard at its pre-WWI nominal parity, one important contributing factor was that “the most articulate opponent [of the return to the pre-WWI nominal sterling peg], John Maynard Keynes, had an off night when given an opportunity to make his case to the chancellor…”

I do not think that we really know this.

Our source for this is Churchill’s private secretary P.J. Grigg. As I wrote in the notes to Slouching Towards Utopia: “P.J. Grigg, Churchill’s Private Secretary at the Exchequer, claimed that Keynes’s arguments at the dinner were unconvincing…. Then again, Grigg’s hostility towards Keynes was so great that he would have been unable to recognize strong arguments had they been made, He did write on the very first page of his memoirs: ‘I distrust utterly those economists who have with great but deplorable ingenuity taught that it is not only possible but praiseworthy for a whole country to live beyond its means on its wits, and who, in Mr. Shaw’s description, teach that it is possible to make a community rich by calling a penny tuppence, in short who have sought to make economics into a vade mecum for political spivs…’” That is aimed directly at Keynes, and well captures Grigg’s total contempt for the man.

But, other than that complaint about what is essentially a single throw-away line in the piece below, I have no complaints. I do have some comments, however, at the end. Meanwhile, read the whol thing:

Barry J. Eichengreen: Sterling’s Past & the Dollar’s Future <https://www.project-syndicate.org/onpoint/the-us-dollar-s-fall-from-grace>: ‘Apr 10, 2025: US President Donald Trump says he wants to preserve the dollar’s international role as a reserve and payment currency. If that’s true, the history of pound sterling suggests he should be promoting financial stability, limiting the use of tariffs, and strengthening America’s geopolitical alliances.

TOKYO – In April 1925, a hundred years ago this month, Winston Churchill, in his capacity as chancellor of the exchequer, took the fateful decision to return pound sterling to the gold standard at the prewar rate of exchange.

Churchill then, not unlike US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent now, was torn between two objectives. On one hand, he wanted to maintain sterling’s position as the key currency around which the international monetary system revolved, and preserve London’s status as the leading international financial center. On the other hand, he, or at least influential voices around him, saw merit in a more competitive – read “devalued” – exchange rate that might boost British manufacturing and exports.

Why Churchill chose the first course is uncertain. The weight of history – British economic preeminence under the gold standard prior to World War I – pointed to restoring the monetary status quo ante. The City of London, meaning the financial sector, lobbied for a return to the prewar exchange rate against gold and the dollar. The most articulate opponent, John Maynard Keynes, had an off night when given an opportunity to make his case to the chancellor.

The effects were much as predicted. Sterling regained its position as a key international currency, and the City its position as a financial center. Now, however, they had to contend with New York and the dollar, which had gained importance, owing to disruptions to Europe from the war and the establishment of the Federal Reserve System to backstop US financial markets.

Also as predicted, British exports stagnated. At current prices, they were lower in 1928-29 than in 1924-25, when the decision to stabilize the exchange rate was taken.

Here, clearly, a strong pound and the high interest rates required to defend its exchange rate were unhelpful. But to attribute the British economy’s poor performance entirely to the exchange rate is to jump to conclusions.

For one thing, the export industries on which Britain traditionally relied – textiles, steel, and shipbuilding – were now subject to intense competition from later industrializers with more modern facilities, including the United States and Japan. The situation was not unlike the competition currently felt by US manufacturing from China and other emerging markets. Then as now, it is not clear that a weaker exchange rate would have made much difference, given the emergence of these rising powers. Nor did the tariffs the United Kingdom imposed in the 1930s revive its old industries.

Moreover, Britain had difficulty developing the new industries that constituted the technological frontier – electrical engineering, motor vehicles, and household consumer durables – even after devaluing the pound in 1931. The US and other countries were quicker to adopt new technologies and production methods, such as the assembly line. Union militancy discouraged investment. Workers with the relevant skills and work ethic were in short supply. Again, these are not unlike complaints heard today from the operators of TSMC’s new semiconductor fab in Arizona or Samsung’s chipmaking plants in Texas.

And, of course, it did not help that the 1930s were marked by trade wars and a decade-long depression.

Notwithstanding these problems, sterling’s position as an international currency survived the 1930s. In fact, the pound regained some of the ground as a reserve and payments currency that it lost to the dollar in the preceding decades. Whereas Britain was broadly successful in maintaining banking and financial stability, the US suffered three debilitating banking and financial crises. The UK maintained stable trade relations with its Commonwealth and Empire under a system of imperial preference that negated the effects of otherwise restrictive tariffs. And it remained on good terms with trade partners and political allies beyond the Commonwealth and Empire, including in Scandinavia, the Middle East, and the Baltics, where monetary authorities continued to peg their countries’ currencies to sterling.

The lessons for those seeking to preserve the dollar’s status as a global currency are clear:

Avoid financial instability, which in the current context means not allowing problems in the crypto sphere to spill over to the rest of the banking and financial system.

Limit recourse to tariffs, since the dollar’s wide international use derives in substantial part from America’s trade relations with the rest of the world.

And preserve the country’s geopolitical alliances, since it is America’s alliance partners who are most likely to see the US as a reliable steward of their foreign assets and hold its currency as a show of good faith.

The US, to all appearances, is going down the opposite path, risking financial stability, imposing tariffs willy-nilly, and antagonizing its alliance partners. What was achieved over a long period could be demolished in the blink of an eye – or with the stroke of a president’s pen. Churchill was aware of the risks. As he put it, “To build may have to be the slow and laborious task of years. To destroy can be the thoughtless act of a single day”…

However, while I have no complaints, I do have additions:

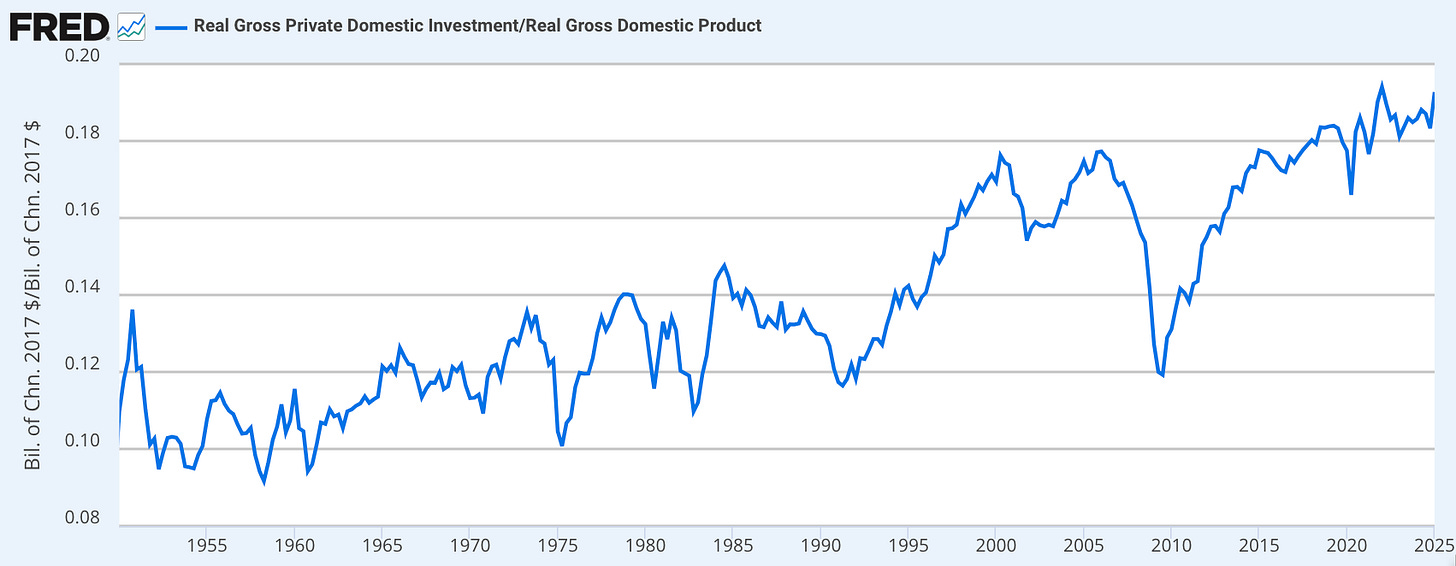

As people have been noodging me in email, it would be much better framing for those of us who want to keep the dollar’s exorbitant privilege to focus discussion not on America’s “trade deficit” but on its “investment surplus”:

Too often, discussions about the U.S. trade balance are framed in alarmist tones: the trade deficit is presented as a sign of economic weakness, of deindustrialization, or of financial imprudence. But this is an aspect of the bag-of-words nature of language, and of the English language in particular. “Deficit” sounds weak and bad. “Surplus” sounds strong and good. However…