Paul Krugman Says: At Every Moment Either Larry Summers or I Am Right—But Your Problem Is You Can't Tell Who When We Disagree

Both Krugman and Summers can be right—just not always both at the same time. Rethinking the use of the 1970s experience to understand the 2020s inflation: macroeconomic misfires, and why humility beats certainty…

If you thought 2020s post-plague inflation was a rerun of the 1970s and was persistent, you weren’t alone—but you were wrong. But if you were on Team Transitory and thought that the 2020s post-plague inflation was going to be small because the Phillips curve was flat, you were wrong also. First “Team Transitory” got blindsided. Then “Team Persistent” got blindsided.

This made me laugh:

Paul Krugman: ‘On any given macroeconomic issue… you can count on either Larry [Summers] or me having been right. The problem is you don't know which one…

It’s twue! It’s twue!

The context:

Paul Krugman: A Conversation With Barry Ritholtz <https://paulkrugman.substack.com/p/a-conversation-with-barry-ritholtz>: ‘2022 and inflation… Larry Summers… made a successful forecast of the inflation spike and got enormous credit for it, and then made an absolutely disastrously wrong prediction about what it would take to get inflation down…. I was on the other side of both those arguments and was wrong the first time and right the second time….On any given macroeconomic issue… you can count on either Larry or me having been right. The problem is you don't know which one. But what struck me there, first… are… reasons to think that Larry in ‘21, ‘22 was right for the wrong reasons…. I just thought that the methodology was all wrong, that he was extrapolating from experience, post-1970s, and 2022 was not 1980…. It's not the fact that he was wrong, it’s… that he was wrong for the wrong reasons…

And I do concur 100% with with Paul Krugman’s belief that to understand the post-plague inflation by starting from the baseline that this was the 1970s come again was bad methodology. And I was saying so, back in real time, that: “those who look at the US post-Korean War experience and try to generalize from that are, I think, barking up the wrong tree…”

History told us that there were many, many other ways than the 1970s that things could break. The 1970s were unusual both in the then-existing macroeconomic structure and in the pattern of shocks. And it was very clear to me that: “This is, as I say over and over again, not a 1970s like inflationary spiral—not melting the engine—but rather leaving rubber on the road as you rejoin the highway traffic at speed. Rejoining the highway traffic at speed is a good thing to do. Leaving rubber on the road is a necessary consequence of doing that. It’s stupid to complain about it…” The benefit/cost calculus was overwhelmingly in favor of tolerating transitory reopening inflation.

In fact, I would go further than saying that the near-consensus macroeconomic model derived from the U.S. 1970s experience is likely to be a bad fit for other times and places.

I would say that that standard model macroeconomists derived from the 1970s—the belief that, apart from rare supply shocks, inflation next year was going to be inflation this year, plus or minus a price-pressure term that was positive when output was above and negative when output was below “potential”—was not a good fit for the 1970s. You needed to pound on it in order to make it fit. Pound hard. The fact that you are estimating an equation requiring expected inflation to have a stable one-for-one dependence with current inflation means that the computer will do its best to fit the data by driving your estimates of both the natural rate of unemployment and the price-pressure slope-of-the-Phillips curve parameter away from their actual values.

Indeed, using that model led to substantially pessimistic views on what the “natural” rate of unemployment was, views that made policymaking more difficult in the late 1980s and 1990s.

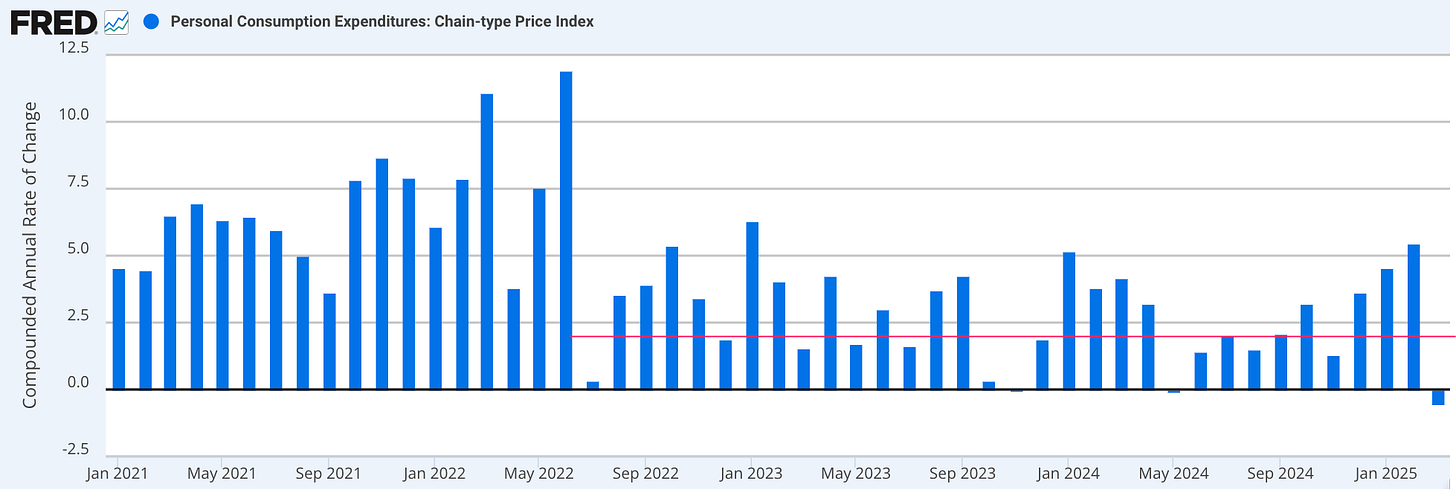

And believing that inflationary expectations had become embedded in the price process meant that Team Persistent was simply not seeing reality starting in July 2022:

But I would also say that people like me (and Paul) who were committed believers in Team Transitory need to spend more time thinking about why we were wrong in 2021 and 2022.

One out is to say two things:

First, that the supply-side “reopening shock” inflation was indeed transitory, but that as it began to ebb the economy was hit by another shock, the Putin shock—one that was smaller, also transitory, and over by the spring of 2023. Indeed, it was all over by June 2023. Thereafter inflation remained very close to target. Moreover, throughout the inflation medium-term expectations of future inflation in the bond market remained nearly nailed to where they needed to be for the Fed to costlessly attain its 2%/year PCE and 2.5%/year CPI target for the annual inflation rate by simply waiting for supply shocks to die away.

Second, that we on Team Transitory were betrayed by our belief that the Phillips Curve would remain flat as the economy reopened post-plague. We should have realized that there is a natural rate of inflation—a rate of inflation below which full employment is unattainable—and that that rate is a positive function of how much structural change we are demanding the economy undergo at the current moment in time.

I do say those two things. But how certain should I be that I am right, and that saying these two things is satisfactory? We should not be too confident that we were wrong for the right reasons.