Models Meeting Structural-Economic Mayhem: Yes, There Is a Great Deal of Analytical Blood—& Error—on the Wall

Inflation is returning. Recession is coming, probably. But how much? How big? How long? The best forecast is to admit that while we can be reasonably confident about directions, we have no good clues as to magnitudes. Honest analysts now have flat posteriors and long tails. It depends, you see, on the strength of feedback loops we do not understand, and that are in any event very different than they were even a decade ago. & when structural change breaks correlations that held in the past, the future will break all our models…

The smart Torsten Slok of Apollo:

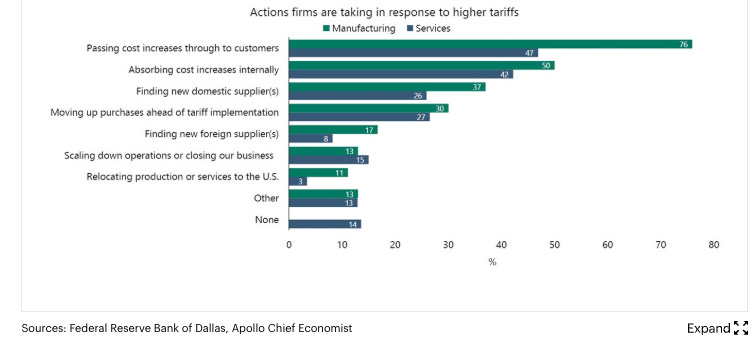

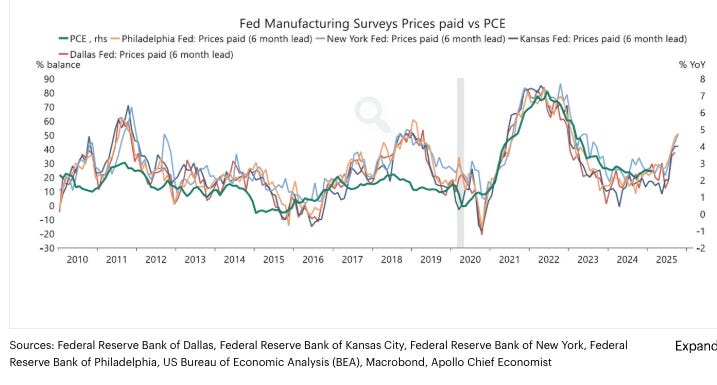

Torsten Slok: After “Liberation” Day <https://www.apolloacademy.com/the-daily-spark/>: ‘Earnings expectations… have been revised down significantly… interest rate differentials no longer drive the dollar… companies are responding to higher tariffs.. [by planning on] passing cost increases through to consumers:

The bottom line is that inflation will be rising significantly over the next six months…

But what is “significantly”. We do not know.

Back up:

Our macroeconomic forecasting models have long been not bad, even OK, at unconditional forecasting. Thus they have served as useful compasses guiding market expectations, and useful background for policy discussions. But these models have succeeded not because they are true, but because the process of estimating them means that the computer has found a way to match historical in-sample correlations. Thus, to the extent that those correlations from the past tend to continue into the future, the models can do their job of giving you a future number that is not far off from what the true future is likely to bring.

This approach serves us very well during periods of relative stability.

However, these models are hopeless when faced with shocks that deviate sharply from historical norms. The COVID-19 plague global health crisis disrupted supply chains, labor markets, and consumer behavior in ways that we had never before seen. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine had far-reaching economic effects simply not found in recent historical precedent. That means that Robert Armstrong had it exactly right when he aptly described the challenges of forecasting as requiring that “any forecast must be made humbly”, for “this is all new”.

It gets worse. Structural changes within the economy render not just traditional models but the practice of forecasting a conditional outcome on the basis of a key relationship extremely hazardous. The labor market, for example, has undergone significant transformations in recent years, with shifts in worker preferences, remote work trends, demographic changes, and the informational ecology of job search profoundly altering the dynamics of employment and vacancies. Larry Summers relied on the Beveridge Curve—the relationship between job vacancies and unemployment—to forecast that the post-plague inflation would not subside without a substantial rise in unemployment, and thus a recession. That forecast rested on bedrock: the Beveridge Curve had, after all, long been reliable, and it definitely had a slope. But Larry was wrong, as the Beveridge Curve crumbled and its slope vanished.

Or look at me. I believed that price-setting behaviors were sufficiently forward-looking to ensure that the inflationary pressures following the post-plague demand surge would be transient: that price-adjustment would be one-and-done. Hence I was very much on Team Transitory as far as post-plague inflation was concerned. But they were not sufficiently forward-looking. It was not one-and-done, but do-do again-and then do yet again. Transitory in the end, but a tide rather than a wave. And then Vladimir Putin decided to remake the Spanish Civil War.

Or look at all of us. We are all perplexed by the resilience of the prices of long-duration assets in the face of rising interest rates. Conventional wisdom suggests that higher rates should dampen the appeal of such assets, yet markets have defied this expectation. The current-thing AI enthusiasm seems to be blinding people to what I see as fundamentals, and leading to a great deal of the shrugging-off of what should be very real concerns that data-center training costs and inference costs will not be followed by profits. Add to that the reality that equilibria are sensitive, as small shocks produce large effects since the largest contributor to a recession is the expectation of such, and it does not take that much irrational exuberance to submerge asset price fundamentals for a while. And our bias toward thinking that asset prices have to return to real reality quickly misleads us.

Thus I do not dare to offer a quantitative forecast right now.

Yes, both higher inflation and unemployment seem very probable indeed over the next year. But the magnitude and duration of such? The distribution of potential outcomes is disturbingly wide, with a significant very unpleasant and very long tail of strongly adverse possible outcomes.

A year ago Andy Haldane had a very nice line: economic forecasting as performance art. That is how I feel.

References:

Anstey, Chris. 2024. “Where’s That Recession? Forecasts Found Wanting.” Bloomberg, February 15. <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2024-02-15/world-economy-latest-forecasting-fails>.

Armstrong, Robert. 2025. “Solving for three variables with markets in chaos.” Financial Times, April 7. <https://www.ft.com/content/ce09bfcc-f84e-4c26-b1c4-616fc23daacb>.

Haldane, Andy. 2024. “Economic Forecasting — Little More than Performance Art for Central Bankers.” Financial Times. April 15. <https://www.ft.com/content/475e1fae-1bf6-4aaf-ba07-e249f09cbc78>.

Slok, Torsten. 2025. “After ‘Liberation’ Day.” The Daily Spark. May 6. https://www.apolloacademy.com/the-daily-spark/.