The Self-Inflicted Slump: How Tariffs Are Pushing the U.S. Toward a VTRR—A Voluntary Trade Reset Recession

A sudden spike in tariffs has small businesses on the ropes, and the broader economy may be next. Yes, individually big businesses can lobby and bribe Trump and Trumpists for loopholes. But small businesses cannot, and they are going to be the things that are most macroeconomicly significant now. This likely recession will be a new kind of recession—not the result of inventory and investment cycles, supply shocks, bursting bubbles, or bank failures, but from brute idiot-policy force, a self-inflicted slowdown driven by tariff shocks and political brinkmanship. Since none of our models have been estimated on such a shock, it is a very brave forecaster who will put it out there right now. And so I am very grateful to Torsten Slok, Karen Dynan, and Adam Posen for doing so…

I see Torsten Slok writing:

Torsten Slok: Probability of VTRR 90% <https://www.apolloacademy.com/probability-of-vtrr-90/>: ‘Tariffs have been implemented in a way that has not been effective, and there is now a 90% chance of what can be called a Voluntary Trade Reset Recession (“VTRR”), see the first chart below. The administration inherited an economy with strong growth, 4% unemployment, positive hiring, and a substantial tailwind from investments. US and international investors are building infrastructure, next-generation factories, and data centers. The Inflation Reduction Act increased capex, and the US was poised for a substantial increase due to energy supply additions, increased defense production, and deregulation. But implementing extremely high tariffs overnight hurts many businesses; particularly small businesses because the tariff must be paid by the business when the imported goods arrive in the US. Small businesses that have for decades relied on a stable US system will have to adjust immediately and do not have the working capital to pay tariffs. Expect ships to sit offshore, orders to be canceled, and well-run generational retailers to file for bankruptcy.

To make exceptions for large businesses that have the flexibility and resources to handle unforeseen expenses but not small businesses does not make sense. The challenges for small- and medium-sized enterprises are now a macro problem for the US economy, where small businesses account for more than 80% of US employment and capex, see the second and third chart below. One way to quantify the coming negative impact on GDP is to compare the current tariff increase with the tariff increase observed during the trade war in 2018…. The US average tariff rate increased from 2% to 3%, and studies… (here and here)…. The negative impact on GDP in 2025 could be almost 4 percentage points, not including additional non-linear effects because of the current increase in uncertainty for consumer spending decisions and business planning…

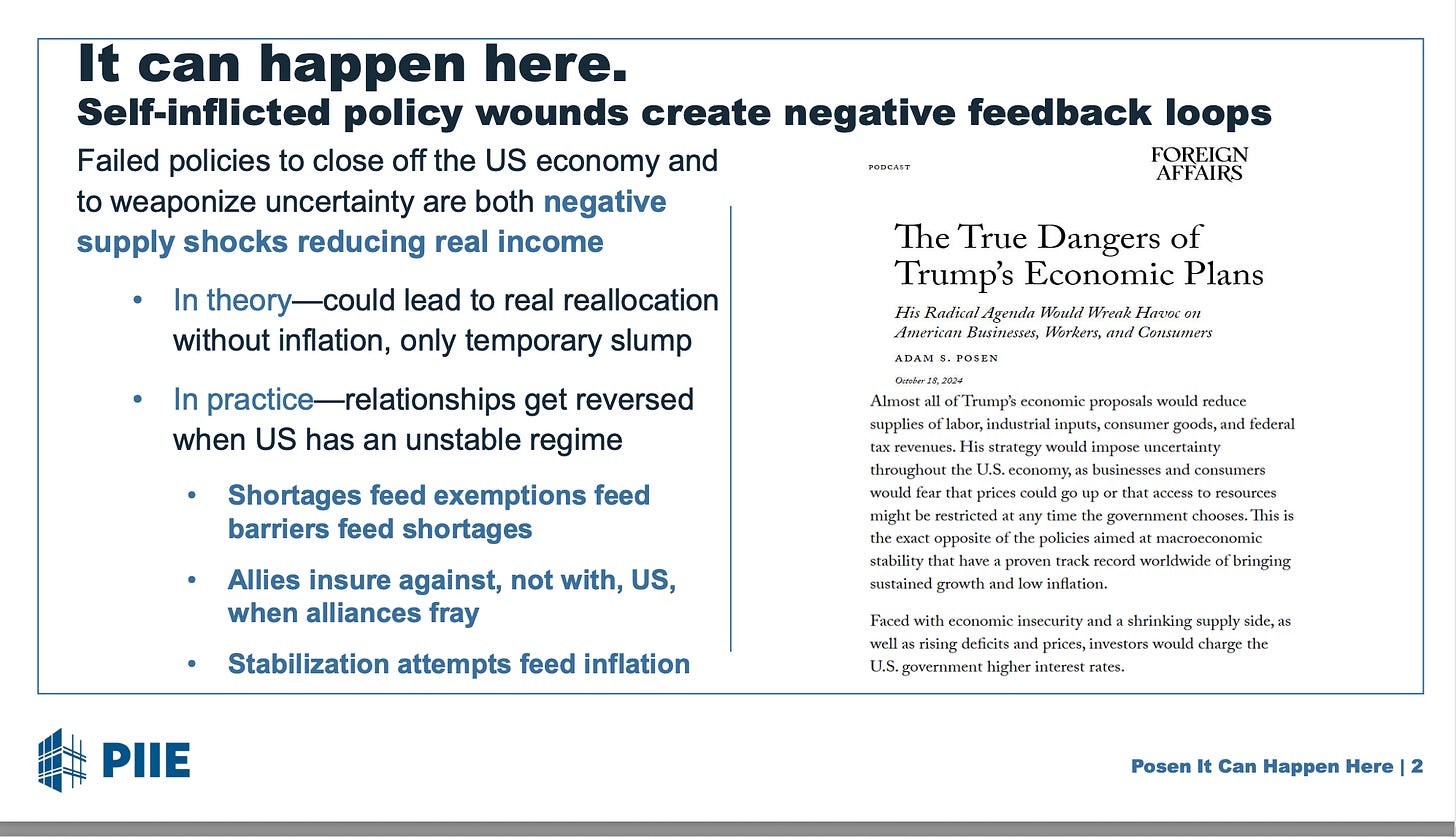

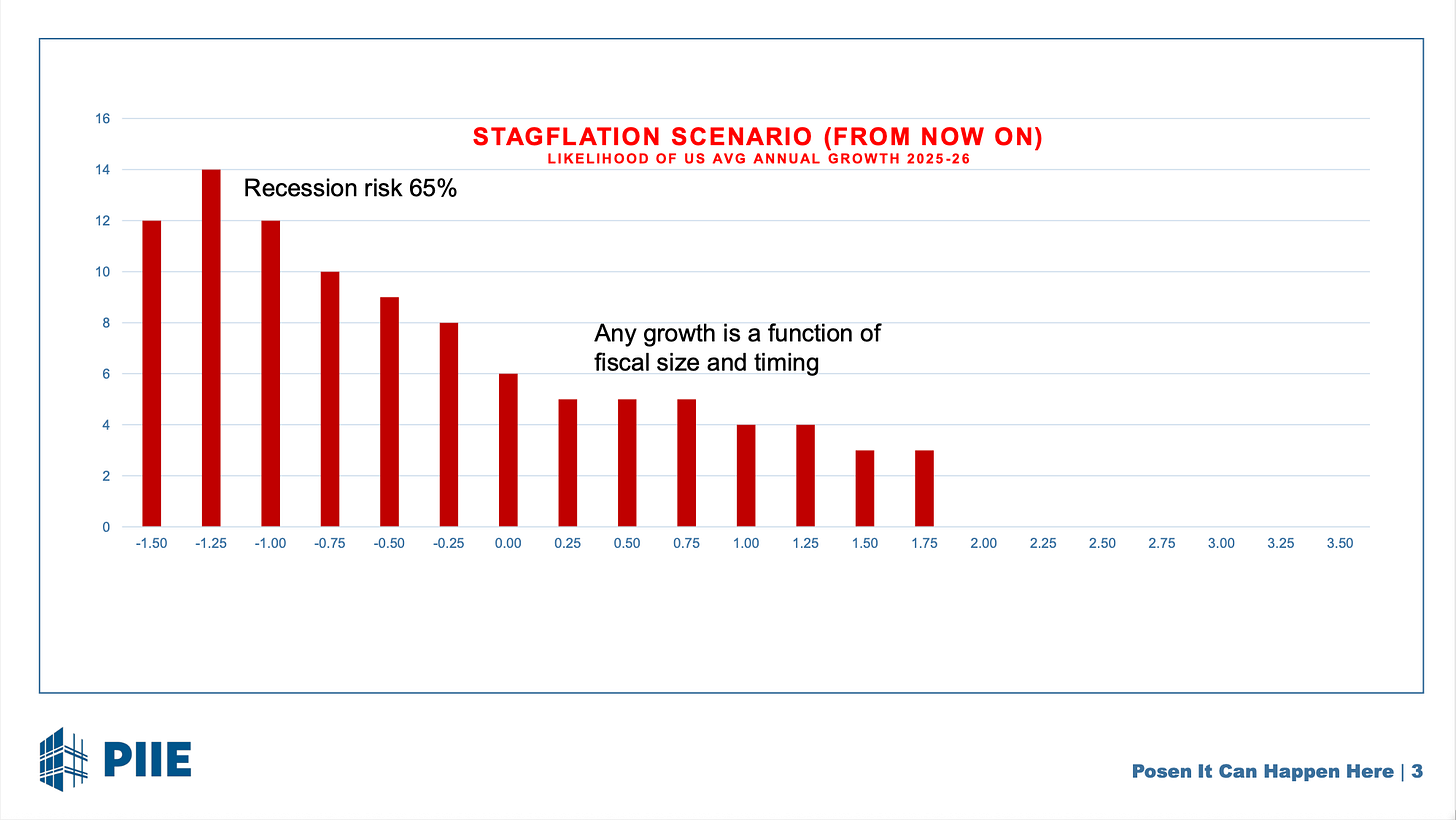

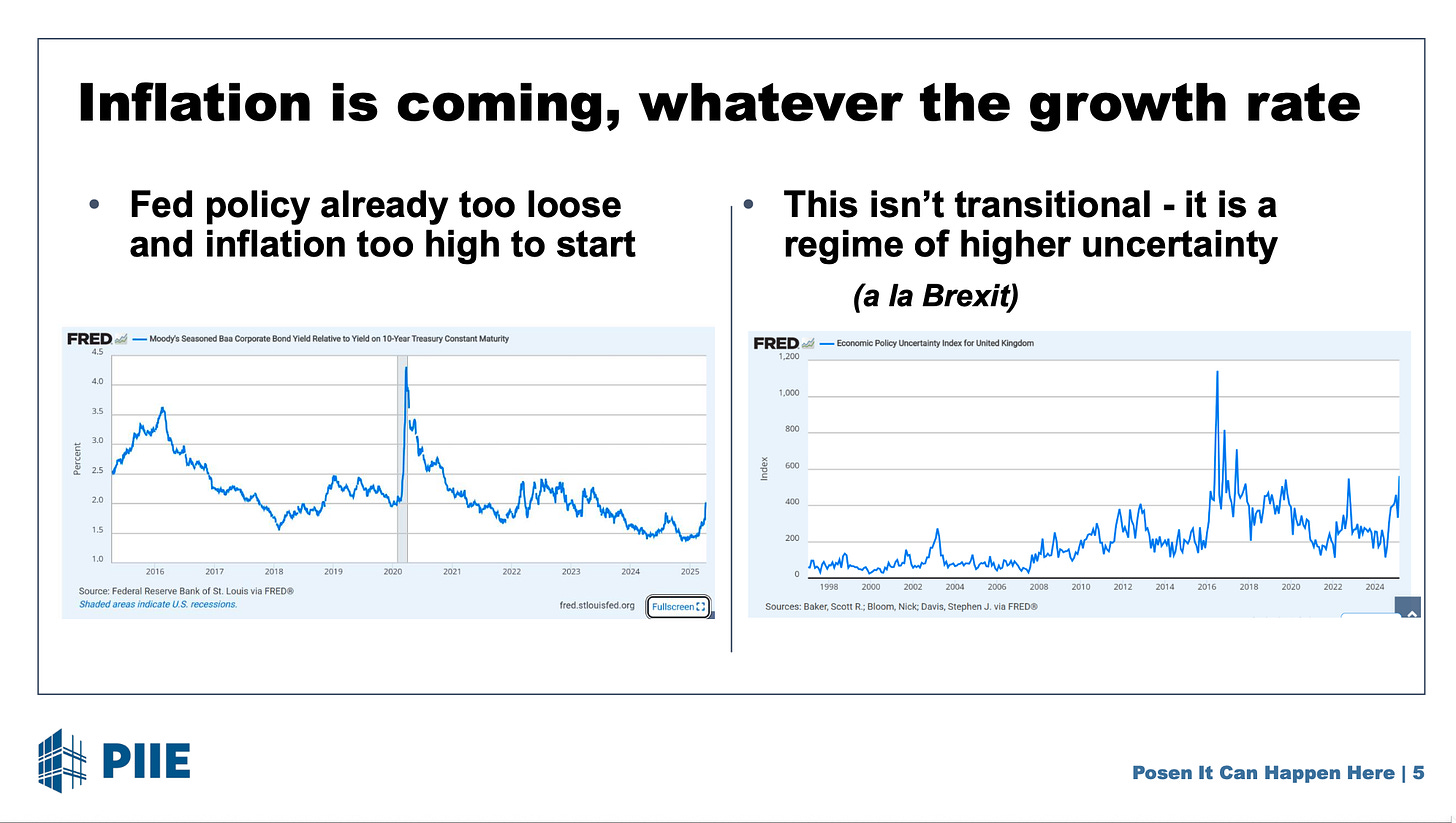

While Adam Posen says:

Adam Posen:

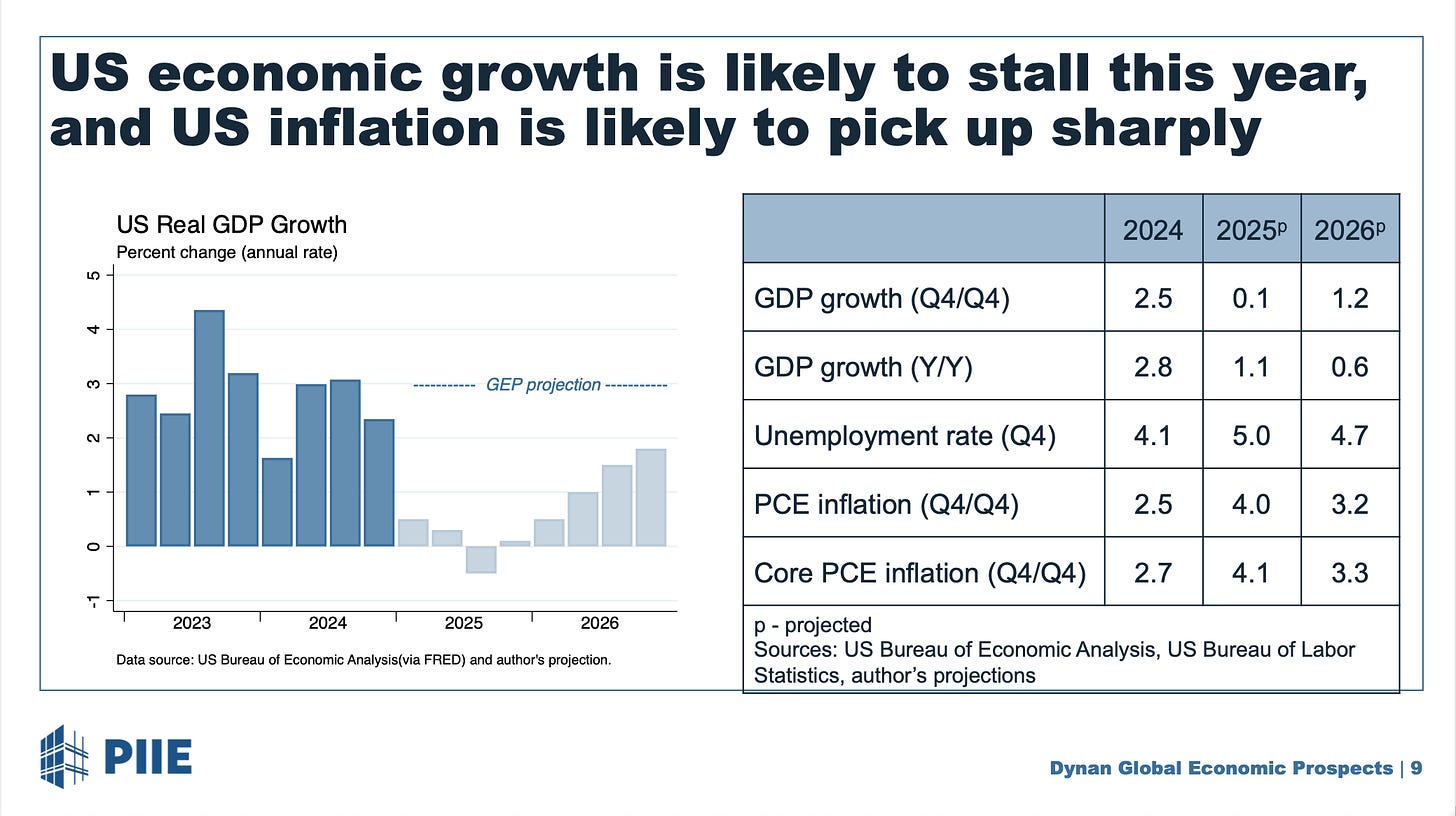

And Karen Dynan:

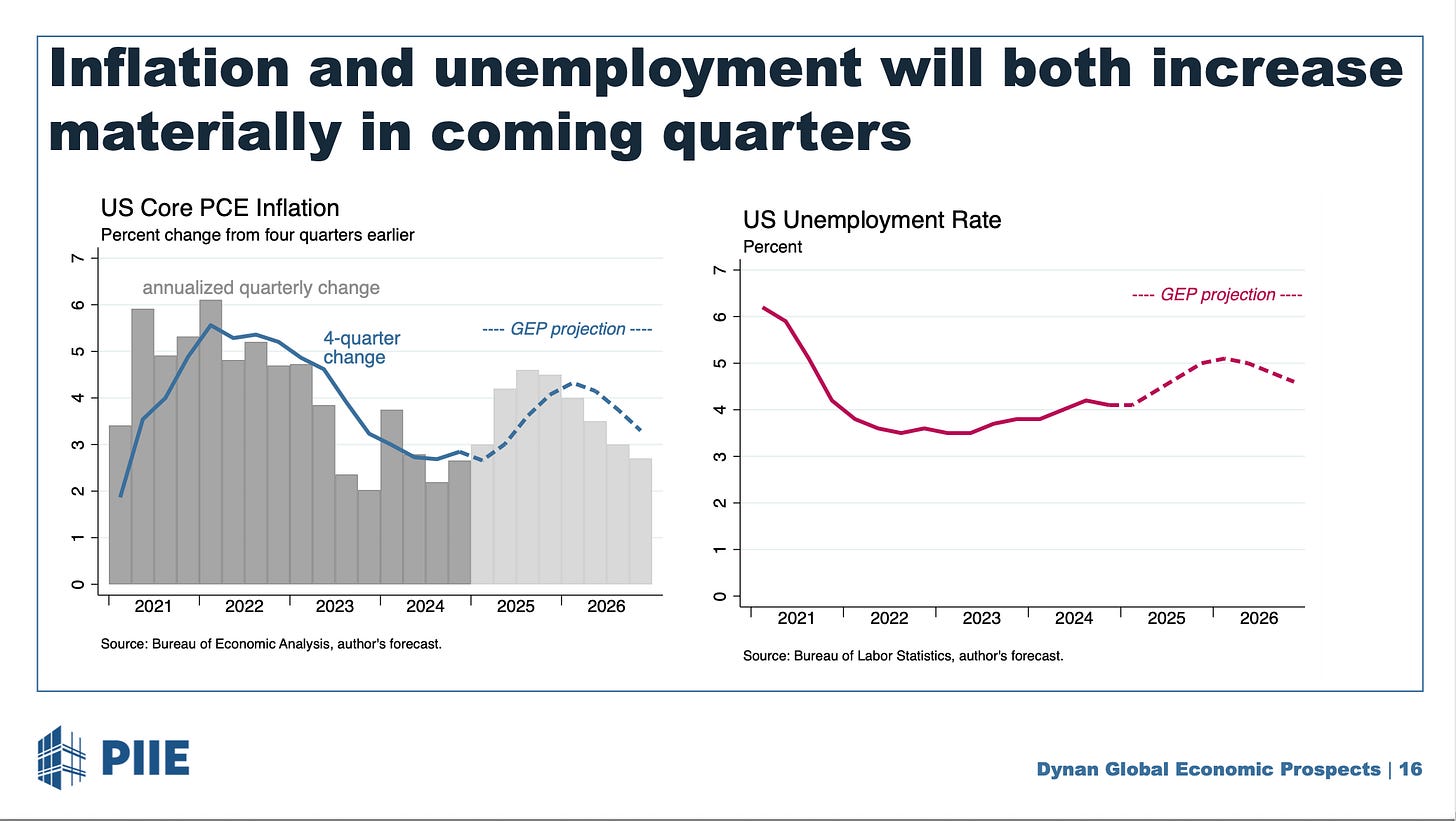

Karen Dynan:

Karen is the only one not making a recession call—and she is on the edge: a 40% chance of recession, and a long and dangerous tail should the policy shocks set a self-sustaining feedback downward spiral into operation.

What do I think? I think that there are very few times when market timing—diminishing the global stock-market weight in your portfolio from the 1.5 or so that it ought to be to 0.5 or less—has been worth doing in the past 150 years.

But it really looks like now is one of them.

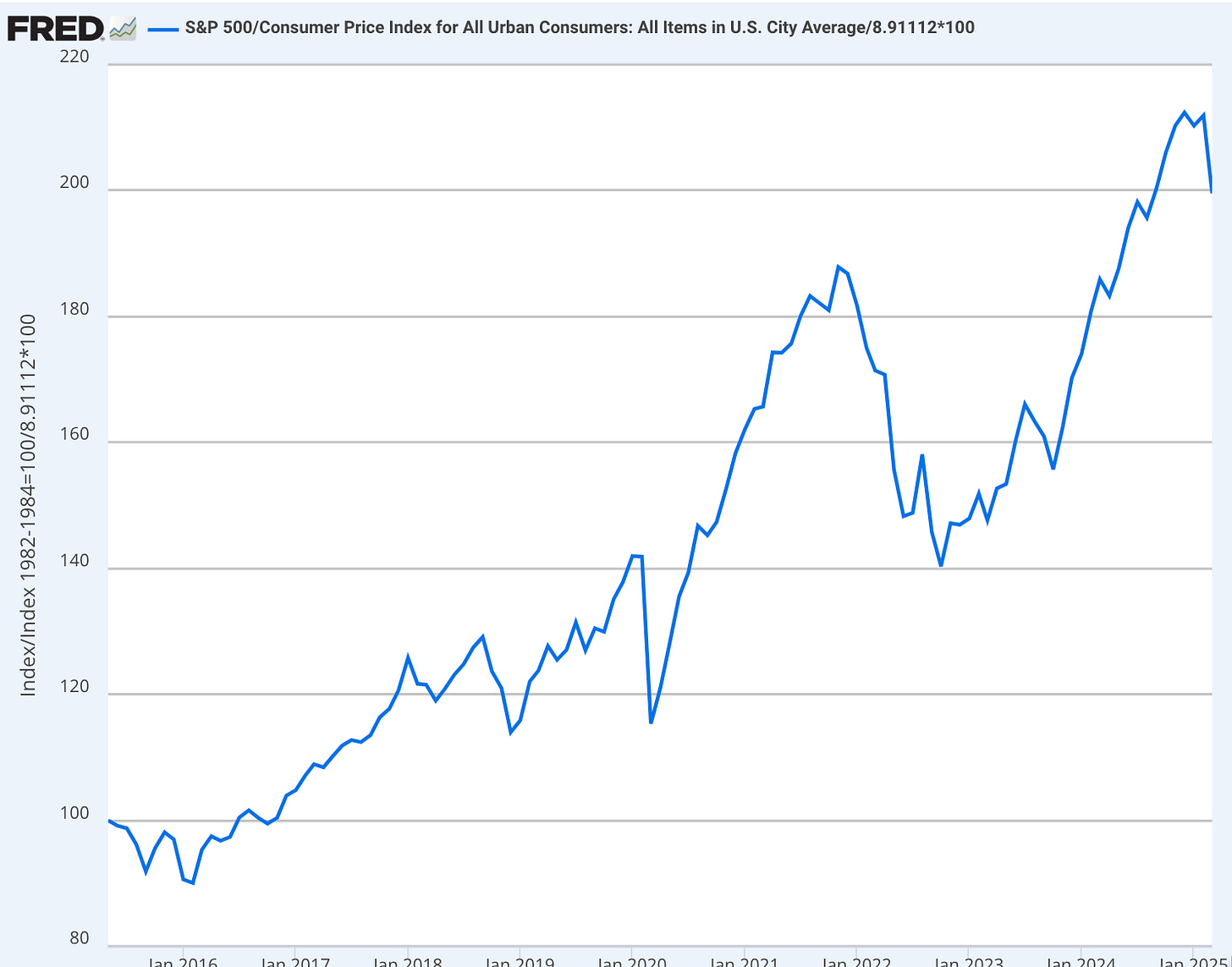

The disjunction between the political-economic Trump situation and real market values:

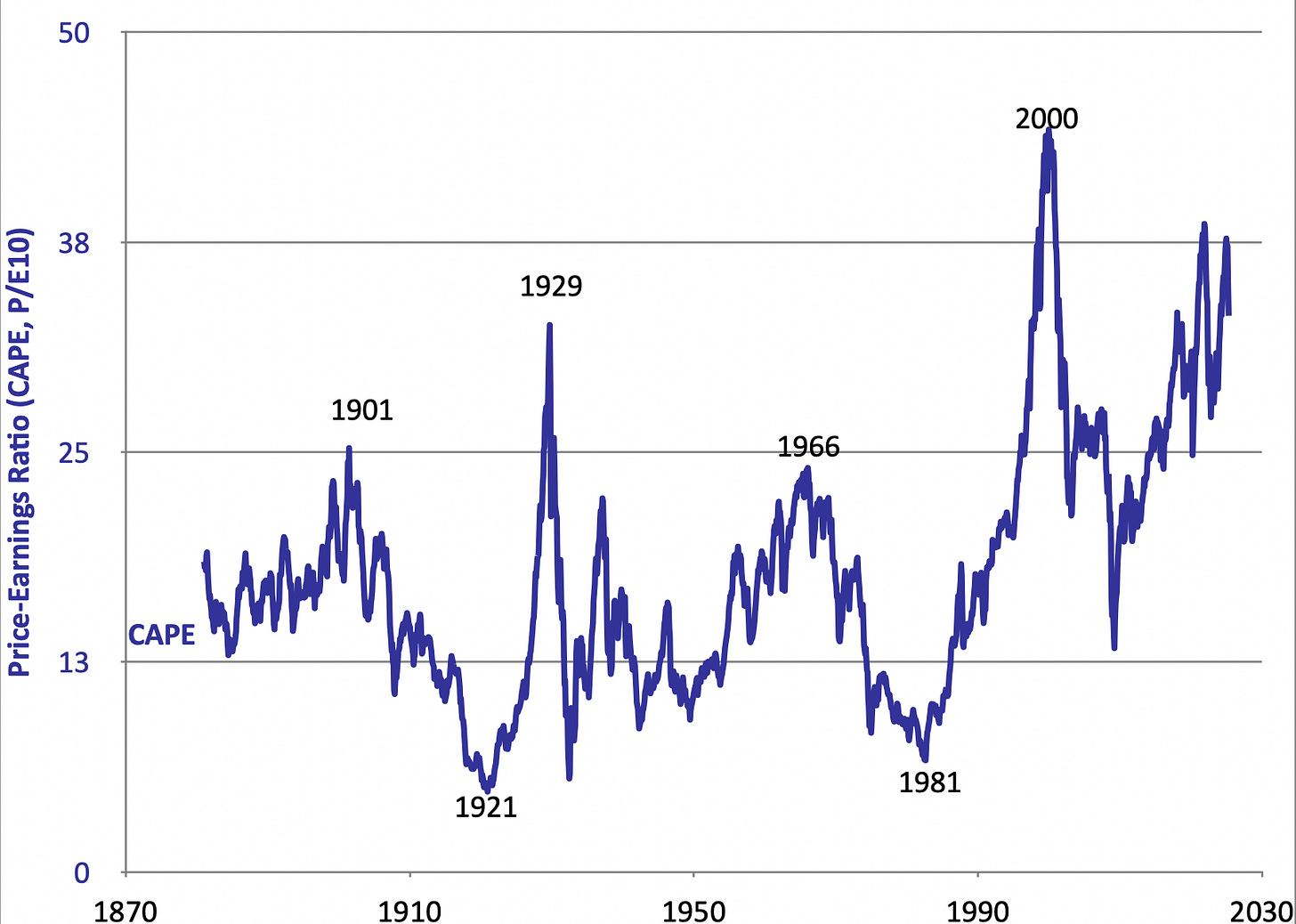

and price/earnings ratios:

is palpable. There is not much of an equity premium to be harvested even if CAPE returns only to the value of 25, which we then thought was very high, it had back in 2015.

Plus even if price/earnings ratios remain at their current levels, recognize that the U.S. has just inflicted a likely recession on itself in the short-term and a BREXIT-class uncertainty-generated growth slowdown in the long-term. That BREXIT-class disaster looks likely to me to be between 1% and 2% per year over the next two decades. International trade in goods is massive. And people pretending that doesn’t matter because we are overwhelmingly a service economy ignores how much of service-sector productivity is linked to and indeed derivative from the goods economy.

And downward tail risk is very high.

And I cannot see any way out, short of Trump resigning, or appointing a competent regent.

These tariffs—whatever they ultimately turn out to be, and even if they would have been a nothingburger if properly prepared and rolled out—dropped suddenly and with little preparation, are inflicting heavy costs on the backbone of the American economy. Expect canceled imports, idle container ships, and an uptick in bankruptcies. The U.S. economy had momentum. Investments in manufacturing, infrastructure, and data centers were being propelled by the Inflation Reduction Act, energy expansion, and defense production. But a policy move with no possible economic strategy justification is bringing the growth machine to a halt. Right now we have to hope that there is no unknown systemic vulnerability out there that can—like mortgage-backed securities falsely marketed as AAA assets—trigger a true financial explosion.

Paul Krugman thinks it likely that there are such systemic vulnerabilities, although we still do not see where they are:

Paul Krugman: A Primer on Financial Crises, Part II <https://paulkrugman.substack.com/p/a-primer-on-financial-crises-part>: ‘The April storm… [when] Trump shocked the world by announcing that he was imposing very high tariffs on just about every nation America trades with. When Trump took office the average U.S. tariff rate was only about 3 percent. In one fell swoop he pushed it above 20 percent, higher than it was after… Smoot-Hawley…. The specifics of market reaction were peculiar…. [(1)] Interest rates on U.S. government debt rose. This was peculiar because normally the increased likelihood of a recession… will cause interest rates on US government debt to fall. Moreover, U.S. interest rates have historically fallen in uncertain times…. [(2)] Economists normally expect that tariffs… will cause the dollar to rise… [plus] rising U.S. interest rates should also have boosted the dollar. Instead, it fell…. [This is] something we… see in emerging markets that lose… confidence…. It’s unprecedented to see what looks like capital flight from the United States.

But[is] capital flight… the whole story? I don’t think so…. We’ve also seen interest rates on relatively risky or thinly traded assets… shoot up…. Bonds… protected against inflatio… rose so much that the spread between these bonds and regular bonds, often seen as a market forecast of inflation, went down…. [But] tariffs will surely lead to higher, not lower inflation…. That spread plunged during the 2008 crisis and again in 2020, so it suggest[s]… that we may be in the early stages of another financial crisis…. What’s the mechanism? As best I can tell, we’re looking at a potential balance sheet crisis focused on hedge funds… [that] need to reduce their exposure to market volatility by selling assets. This drives the prices of assets on their balance sheet down, which in turn requires that they sell even more assets to further reduce their exposure…

There are moments when politics and markets seem to diverge so sharply that it seems inevitable that something has to give.

This isn't just a short-term policy mistake—it’s a structural own goal. And it comes at a time when the U.S. had all the ingredients for an investment-led growth boom. Instead, we may be facing a downturn driven entirely by policy error.