The Fed's Balancing Act Does Not Seem to Me to Be Balanced. I Wish They Would Explain Their Thinking

A more hawkish Fed meeting communiqué than I confess I had expected to see today; as I say over and over again, optimal control theory tells us that when you are near target your control should be near-neutral; yet it is not so; and the FOMC does not seem to think that it should be so…

I have my talking points for the four Fed-Watching interviews I gave today:

Two-thirds of the time the Fed comes close enough to achieving the dual mandate for government work—approximately matchs the total amount of spending in the economy with the ability of people to make and sell things and earn good wages and profits, at more-or-less the prices they had expected.

Too little spending relative to productive capacity gives you high unemployment.

Too much spending causes shortages and prices people see as unreasonable, which really frustrates people.

The market cannot do this balancing. Some light-handed central planning is necessary to match aggregate demand to aggregate supply. That is what the Federal Reserve does.

For a long time other countries had central banks and the United States did not. The Jacksonian political current greatly feared a central bank controlled by Philadelphia and later New York financiers.

After the financial crisis and depression of 1907, progressives managed to assemble a political coalition to establish the Federal Reserve System.

The Federal Reserve was and is different from other central banks. Other central banks had a head office in their capital that controlled everything. The U.S. had twelve regional banks, one in each Federal Reserve district. Originally, they were only loosely coordinated by the committee of the Governors of the Federal Reserve in Washington.

Governors of the Federal Reserve were not supposed to be bankers, but rather to represent the interests of labor, mining, agriculture, commerce, industry, etc.—people who cared about an adequate supply of credit, as opposed to the banker-financier fixation on price stability.

The same held for the regional banks: the share of members of the Boards of Directors of the regional banks who could be bankers was, originally, capped at one-third.

The Fed’s explicit dual mandate arrived in 1976 with the Humphrey-Hawkins bill.

Over time, the explicit dual mandate has changed the arguments that find purchase within the Federal Reserve. This is in striking contrast with, say, the European Central Bank’s more conservative stance.

The U.S. system has performed much better than the ECB since the plague: faster output growth, higher employment growth, no greater cumulative inflation, no greater current inflation.

It strongly looks to me like the dual mandate led the Fed to make a better decision.

The Federal Reserve’s 2% annual target for the core Personal Consumption Expenditures chain price index creates a mindset where people think the Fed is in a race to hit this target—sprinting at full speed to the tape, if you will. That is the wrong metaphor.

The correct metaphor is that of steering a boat. You avoid drastic movements as you approach your target: if you are a little bit off, you move the tiller a little bit.

Currently, with inflation slightly above target, the Fed’s policy should be only slightly aimed at cooling the economy—unlike a year and a half ago when substantial restriction was appropriate. Yet that is not what Fed policy is: substantially but not severely restrictive is how I would characterize it.

MOST IMPORTANT: Chairman Jay Powell and his committee have faced an extraordinary series of macroeconomic shocks, unmatched since World War I and II. He and his committee have done a remarkable job navigating the U.S. economy through this, ensuring almost everyone has a job and that people are by and large in the right jobs, given the economic changes accelerated by the plague.

Their policies resulted in a two-year period of moderate inflation, which now appears to have ended: if this is not a soft landing it will be a great surprise, because you cannot point to anything around us that says that it is not.

This moderate inflation was a small price to pay for avoiding greater economic damage to the level and sectoral composition of employment. Think of it as like the rubber you leave on the road when you rejoin the highway at speed. You certainly don’t want to make your tires go bald prematurely. But you really, really don’t want to get rear-ended.

It was an interesting lunchtime (here in California) set of communications from the Fed today. Briefly:

The federal funds rate target range is maintained at 5.25% to 5.5%.

The Fed says: future adjustments will be based on incoming data, economic outlook, and the balance of risks.

The Fed does not anticipate reducing the target range until inflation is moving sustainably towards 2%.

The labor market has balanced, with the unemployment rate at 4.1%.

Inflation has decreased significantly from a peak of 7% to 2.5%.

GDP growth moderated to 2.1% in the first half of the year, with consumer spending and investment showing solid performance.

Despite progress, inflation remains slightly above the 2% goal, with core PCE prices rising 2.6% over the past year.

No decisions had been made regarding future meetings, including September.

Additional consistent positive data on inflation is needed to trigger the start of rate cuts.

Chair Jay Powell reportedly focused on the importance of balancing the risks of reducing policy restraint too soon versus too late—and said that right now the risks were close to balanced.

Yes, major challenges spring from the lagged effects of monetary policy.

The Fed is a technocratic, apolitical actor.

This leaves those of us who believe that policy is currently substantially restrictive and that inflation has been moving sustainably toward 2% for more than a year puzzled.

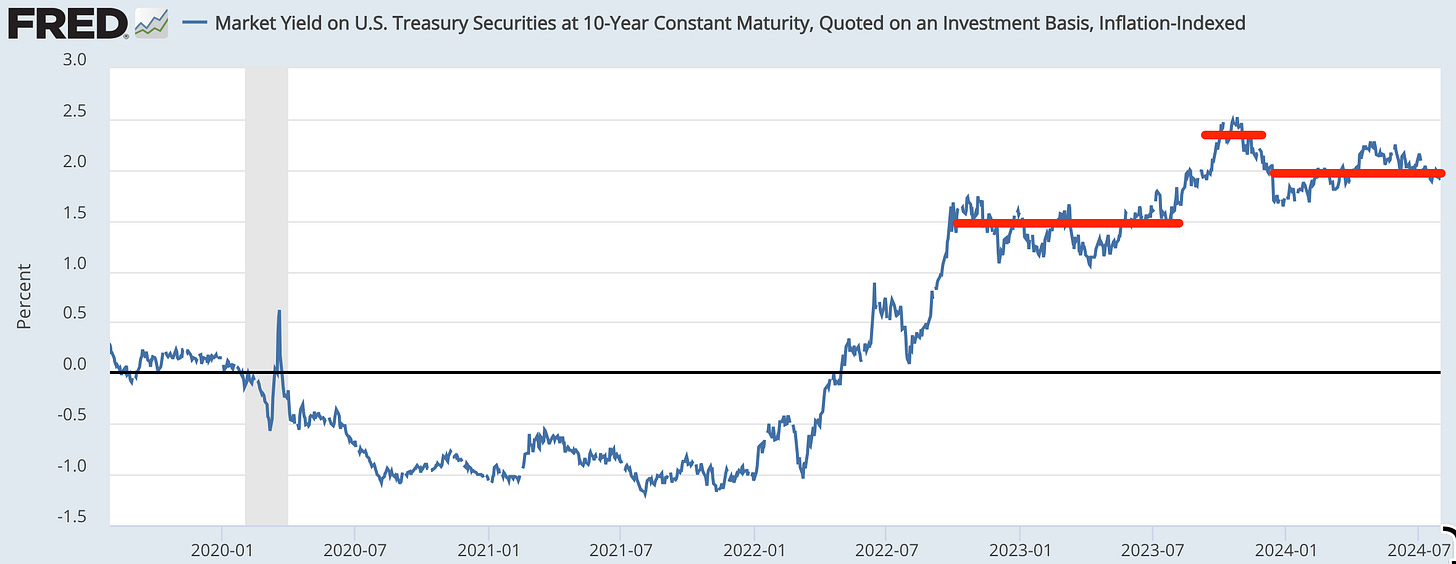

This leaves me especially puzzled given that the variable I grasp at to understand the stance of monetary policy—the ten-year real interest rate on Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities—is today noticeably higher and more restrictive than it was during the October-2022 to July-2023 period during which inflation went from being moderate and annoying to low, in the sense of being not that many hairs’ breadth different from its target:

2024-07-01 We: Federal Reserve FOMC Statement:

Federal Reserve issues FOMC statement

For release at 2:00 p.m. EDT

Recent indicators suggest that economic activity has continued to expand at a solid pace. Job gains have moderated, and the unemployment rate has moved up but remains low. Inflation has eased over the past year but remains somewhat elevated. In recent months, there has been some further progress toward the Committee’s 2 percent inflation objective.

The Committee seeks to achieve maximum employment and inflation at the rate of 2 percent over the longer run. The Committee judges that the risks to achieving its employment and inflation goals continue to move into better balance. The economic outlook is uncertain, and the Committee is attentive to the risks to both sides of its dual mandate.

In support of its goals, the Committee decided to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 5-¼ to 5-½ percent. In considering any adjustments to the target range for the federal funds rate, the Committee will carefully assess incoming data, the evolving outlook, and the balance of risks. The Committee does not expect it will be appropriate to reduce the target range until it has gained greater confidence that inflation is moving sustainably toward 2 percent. In addition, the Committee will continue reducing its holdings of Treasury securities and agency debt and agency mortgage‑backed securities. The Committee is strongly committed to returning inflation to its 2 percent objective.

In assessing the appropriate stance of monetary policy, the Committee will continue to monitor the implications of incoming information for the economic outlook. The Committee would be prepared to adjust the stance of monetary policy as appropriate if risks emerge that could impede the attainment of the Committee’s goals. The Committee’s assessments will take into account a wide range of information, including readings on labor market conditions, inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and financial and international developments.

Voting for the monetary policy action were Jerome H. Powell, Chair; John C. Williams, Vice Chair; Thomas I. Barkin; Michael S. Barr; Raphael W. Bostic; Michelle W. Bowman; Lisa D. Cook; Mary C. Daly; Austan D. Goolsbee; Philip N. Jefferson; Adriana D. Kugler; and Christopher J. Waller. Austan D. Goolsbee voted as an alternate member at this meeting.

For media inquiries, please email media@frb.gov or call 202-452-2955.

And .pdf copies of the FOMC statement, the Powell press conference opening statement, and the Powell press conference Q&A: