Chocolate in the Context of the World Market: What Is the Global Left's View?

Wondering if I can and should try to open up some lines of communication with the “global left”…

This, last month, on June 19:

Timothy Burke: The News: We’re All Lost in the Super-Market: ‘Reading… about the increase in durian production…. We know what comes next in the case of durian. Bigger businesses will elbow in… rent-collecting will extract more…. What makes durian special will become less special, less connected to regional and local culture… standardization… losing flavor and smell…. Labor will get squeezed… methods of cultivation will get more and more damaging and extractive… <https://timothyburke.substack.com/p/the-news-were-all-lost-in-the-super>

And yet, and yet, THE VERY PREVIOUS DAY, on June 18:

Timothy Burke: Gastrodome: Easy Living: ‘I always have ambitions to write up a storm the day after my grades are turned in, but it usually takes me two weeks to really get going…. It’s a few weeks of cooking, reading, arguing with friends about academia, and so on before I get back into the guts of some manuscripts…. I had some lamb stew cubes, I wanted to make a kind of curry preparation, but I also had a fair amount of puff pastry in the freezer and I wanted to free up some room. So I kind of worked my way through what I had and it came out pretty well. I cooked broth and wine with a roux, a mirepoix of onion, garlic and carrot and and a Kashmiri-style curry mix, added the browned lamb cubes once it thickened just a bit, and let that stew for a while. Then I put that in puff pastry, added some zucchini and turnip, and baked it until the pastry browned. Given the amount of unplanned half-assery involved, it came out pretty damn good… <https://timothyburke.substack.com/p/gastrodome-easy-living>

Notice what is not said in the second, earlier, extract:

These New Zealand lamb stew cubes—processed, frozen, and shipped 9000 miles—have lost quality, flavor, and smell as they have entered the global market and shifted from local artisan products to technofarmed and globally transported…

the frozen factory-made puff pastry is a pale shadow of what it should be, having lost the connected cultural context it had when it was handmaid by Frenchwomen in their traditional environment using traditional methods…

This Kashmiri-style curry-spice mix is a prepackaged abomination…

This wine is not native to Greater Philadelphia, and overpriced because of rent-collecting middlemen…

Come to think of it, neither is the turnip native to Greater Philadelphia—it, too, is available to him only because of the Columbian Exchange. The zucchini as we know it is a creation of early 20th-century Italian agricultural capitalism. And I will give him neither the mirapoix nor the roux—celery, onion, and carrot are only grown in the Americas because of the Columbian Exchange, and in Greater Philadelphia he should be trying to use cornmeal as a thickening agent…

On the one hand, Timothy Burke is, in his lane, one of the best we got. On the other hand, there are, in the first post, a lot more pseudo-lefty sociology-speak tropes not contained in the excerpt I started with. like:

“Clever agronomists… push[ing] other mushrooms towards a more ‘truffle’ flavor… [but] part of what made the flavor desirable was its rarity and the desire ebbs…. The tragedy of the commons follows… hyper-exploitation… unsustainable harvest…. Land… fall[s] into the hands of large monopolies, who then… subordinate and exploit human labor… you go from a region where individuals gathered truffles with their dogs or pigs and received the profits directly… to a world where people get paid a few pennies to gather truffles on land owned by a single organization…” Am I really supposed to believe that the economies and communities of Périgueux are oppressed humans deprived of agency ground under the bootheel of a malign French technoagrocapitalism?

“What started as a rush for durians ends with replanting a clear-cut rainforest to produce biofuels because synthetic durian flavor mass-produced in Guangzhou has been added to everything from ice cream to pasta sauce and the value of real durians has crashed, or real durians are being re-routed now exclusively to high-end markets far from where they are grown…” Producing carbon-neutral biofuels in order to reduce global warming is supposed to be a bad thing? Durian-flavored ice cream is supposed to be a bad thing (you can get it: <https://www.mavenscreamery.com/durian-ice-cream>)? Biochemists are now producing artificial durian flavor—but Shenzhen Tangzheng Bio-Tech Co is, not surprisingly, in Shenzhen and not Guangzhou. The value of real durians has not crashed. And yet real durian has become both more abundant and more affordable.

“It feels less like creative destruction and more like plain destruction. More, it doesn’t feel as if it is coming from what people want or from what people are ready to produce or make, but from some other infrastructure entirely that wants to manage volatility for its own ends, leverage profit to its own interests, and push people at either end of supply and demand out of the way. That, in turn, is why so many people are skeptical if you start trying to explore markets as a basic infrastructure for matching need, desire, labor and production, because in the global economy of the last three centuries, they don’t often seem that way…” But in Germany the average male born in 1810 grew to be 5’6”; in 1980 the average male born in 1980 grew to be 5’11”. In Africa life expectancy at birth in 1925 was 26.4 years; today it is 61.7 years.

How is not Tim Burke’s post of June 18 a sufficient anticipatory rebuttal to the post of June 19?

And how can it possibly be that his lived experience with the global food system on June 18 had exactly zero effect on his thinking the following day, once he had donned the academic rob of a liberal arts professor and read the New York Times story about the Durian boom?

And how does this bear on the question of what insights today’s global left thinks that it has about how to bring a better world within our grasp?

Burke is not alone, consider this, from the good-hearted and far-from-stupid Camila Marcias. She starts out by quoting Alicia Kennedy:

Alicia Kennedy: On Luxury: ‘People will still write… “Wine is a uniquely human celebration”… when that can be said of… nearly everything we eat and drink. Wine’s singularity and significance are rarely challenged…. Chocolate—all chocolate—should… be understood as a luxury, with… cacao terroir named, respected, discussed. But… it’s mocked in the general culture to care about such things as chocolate, or coffee, or sugar…. People who would generally claim to care about matters of social justice or decolonization turn the other way when it comes to the commodities upon which their days and pleasures are built. would prefer the land be exploited somewhere else rather than understand most of what they eat as a luxury, to be regarded as preciously as the August tomato or the wildly priced truffle tasting menu at a fine-dining restaurant… <https://www.aliciakennedy.news/p/on-luxury>

And Camila Marcias then goes on:

Camila Marcias: Decolonising Chocolate: ‘Lindt, Nestlé, Cadbury, Hershey’s, and Mars revolutionized industrial chocolate production… scalability… standardizing formulations… consistent taste…. Ninety per cent of the world’s cacao is grown by smallholders who receive a small fraction of the financial value, while a few large companies capture most of the profit, on the other end, millions of consumers enjoy the final product…. We must decommodify the cacao market…. Producer governments [need to] decoupl[e]… cocoa prices from the commodity exchange market… set… them based on production costs, ensuring a living income for farmers… <https://camilamarcias.substack.com/p/decolonising-chocolate>

Now we can read passages like these in two ways:

We could read them as pleas—somewhat confused and not quite coherent pleas—to live wisely and well, and to be properly mindful of our experiences:

When I eat a ripe cherry in February, grown and harvested in the O’Higgins region, packed and shipped out of Valparaiso, and then transported by sea to Oakland before showing up on the shelves at CostCo, I should recognize how wonderful and miraculous I thing this is: I should recognize that three centuries ago the typical fruit eaten was only as sweet as a modern carrot, that I am blessed that so many people working in the global food system have coöperated and coördinated to bring this to me, and that I owe a great debt to them that I need to do more to repay.

I should recognize how pleasant to the feet and how beautiful to the eye is the handmaid carpet from Pakistan I now stand on, and how my debt to the hand-knotters for providing me with it is not paid by the relatively small share of the cost of the carpet that went to them.

I should pause as I munch through this bag of Quest ranch-flavor tortilla-style protein chips—made from milk protein isolate, whey protein isolate, sunflower oil, caseum casinate, cornstarch, and some twenty other ingredients ending with yeast extract, acacia gum, and stevia sweetener. Fully 6% of my daily protein RDA! Only 140 calories! Only 5g of carbohydrates!—to consider the ingenuity and efficiency of the humans who made these and then delivered them to me as well.

If we read them like this, then, of course, yes: As I said on the “Ezra Klein Show” a year and a half ago:

Drop any one of us in the wilderness and we die…. We… have to be part of… sophisticated division of labor… to survive at all…. I don’t know whether to call it a natural or a societal propensity to engage in gift-exchange relationships with others…. You don’t want to be a moocher, but you also don’t want to always be the person doing the work….

This complicated dance of favors and obligations in which… everyone feels obligated even though everyone is getting enormous amounts from the relationship…. You… have… gift-exchange relationship[s] not just with your neighbors, your friends, and your kins, but… with everyone everywhere else… a unified division of labor and an anthology intelligence…. Realize how very lucky we are… how we all are cousins… involved in this reciprocal exchange…. Take that very seriously.

Adam Smith… has a passage… arguing against mercantilists who say a low-wage economy is… a strong economy…. He says: Wait a minute…. Society is made up of people. If most of the people are starving, that’d be a good society?… [And he says:] “It is but equity, besides, that they who feed, clothe, and lodge the whole body of the people, should have such a share of the produce of their own labour as to be themselves tolerably well fed, clothed, and lodged”….

There are people in Pakistan who wove the carpets that are on the floor of my living room. And every time I walk on them, I should think: I have this wonderful carpet…. I’m trying to keep the dog from barfing on it…. I have an obligation to whoever the guy in Pakistan is… who tied these knots. Whatever I should do, I should take care that they’re somewhere close to the front of my mind…

But there is another way to read passages like this, which is to read it as calling for us to break up and break down the highly imperfect system that we have and replace it with something much more local, much smaller scale, something decolonized and something decommodified. Something in which what are now conveniences—like the handful of semisweet chocolate chips I am about to grab out of the bag in the kitchen—become luxuries and treasured experiences, precisely because we have them so rarely. Something in which what we now view as necessities are beyond the reach of many. And something in which much of what we now call luxury simply disappears.

Let’s make the rubber hit the road. Let’s set out some numbers about chocolate:

A typical small-scale cocoa farmer in Ghana today produces about 400 lbs. of cocoa per acre per year, and farms perhaps 10 acres of land. That means 2 tons of cocoa per year, and at the typical cocoa price (now is not typical!) since 2010 of $3000 per ton, that would mean $6000 a year.

The Ghana Cocoa Board takes the difference—and saves it as a buffer that it says it will spend down if prices fall below $1400 a ton, thus “protecting” farmers against price fluctuations, while also spending it on the COCOBOD’s operations—quality control, transportation, and marketing—and feeding the remainder ito the government’s general account. The government of Ghana is a democracy, characterized by regular, competitive multiparty elections and peaceful transfers of power between the National Democratic Congress (NDC) and and the New Patriotic Party (NPP). It has been so since the establishment of the Fourth Republic in 1992.

Globally, chocolate sales paid by consumers are about $120 billion per year. Global cocoa production today is 5 million tons/year—three times what it was in 1980. At $3000/ton, that is $15 billion/year that would go to cocoa farmers if governments did not have marketing boards.

That is 1/8.

Why is that so small a fraction?

What determines the world price—averaging $3000/ton since 2010, and reaching $10000/ton in April 2024, before falling back to $7500/ton as of the end of June—of cocoa?

Well, it is not that Big Corporate Cocoa exercises monopsony buying power on the world market. If it did, the price would not have jumped from $2200/ton in October 2022 to $3000/ton in May 2023 and then up to $10000/ton, would it?

The Big Six chocolate makerts and sellers are Mars (18%), Mondelez (11%), Ferrero (10%), Hershey (8%), Nestle (7%), and Lindt (4%)—a total of 58%, leaving 42% for the fringe. In an anonymous commodity market, that is not enough concentration to maintain a cartel on the cocoa-buying side. And that is also not enough concentration to maintain a cartel on the chocolate-selling side.

Mondelez—the largest public chocolate-making company, and thus the one with the most readily available accounts—had total chocolate sales in 2023 of $14 billion, cocoa costs of $2 billion, and reported profits from chocolate of $2 billion as well.

What happened to the other $10 billion that flows through Mondelez?

It does not, contra Camila Marcias, go to the shareholders of Mondelez as one of the “few large companies capture most of the profit”—we already accounted for that in the $2 billion of Mondelez’s profit. (Figure $18 billion/year in profit for the industry as a whole.)

That other $10 billion/year flowing through Mondelez (figure $97 billion/year for the industry as a whole) goes to everyone else working in the chocolate-industry value chain besides the farmers . They don’t see themselves as exploiters—they see themselves as getting about what they could get using their skills and location to work in some other job in some other industry. Plus they do, if they are lucky, get the smell, and the taste, as they work making, transporting, distributing, and marketing chocolate.

And then, for the industry as a whole, there is (if the Ghana COCOBOD is typical) the $7.5 billion/year going to governments in countries where cocoa is grown, and the $7.5 billion/year going to the farmers.

Plus there is another part of the picture: the difference between exchange-value and use-value.

Ask all of the chocolate consumers worldwide what is the maximum that they would pay in order to (a) consume as much chocolate as they do rather than (b) consume no chocolate at all, and you could probably get the use-value of world chocolate production up to $250 billion/year.

And so we have, finally, a tentative and rough accounting for a typical year:

$130 billion: use value to consumers (in excess of what they pay).

$18 billion: profits to corporate shareholders, including option-inentivized managers

$97 billion: incomes to non-grower workers in the chocolate-industry value chain.

$7.5 billion: revenue to government cocoa marketing boards.

$7.5 billion: incomes of cocoa farmers.

What do we think of this?

That $7.5 billion flowing to farmers seems absurdly low as a share of the total use-value of $250 billion, doesn’t it?

It often works this way. It is a fact that in a competitive market economy:

Surplus is shared among producers and consumers when both supply and demand are elastic.

When supply is elastic and demand is inelastic, the lion’s share of surplus goes to consumers.

When supply is inelastic and demand is elastic, the lion’s share of surplus goes to the owners of the key limited resources that keep supply from being more elastic.

And the medium- and long-run supply of cacoa (but definitely not the short-run supply!) is highly elastic.

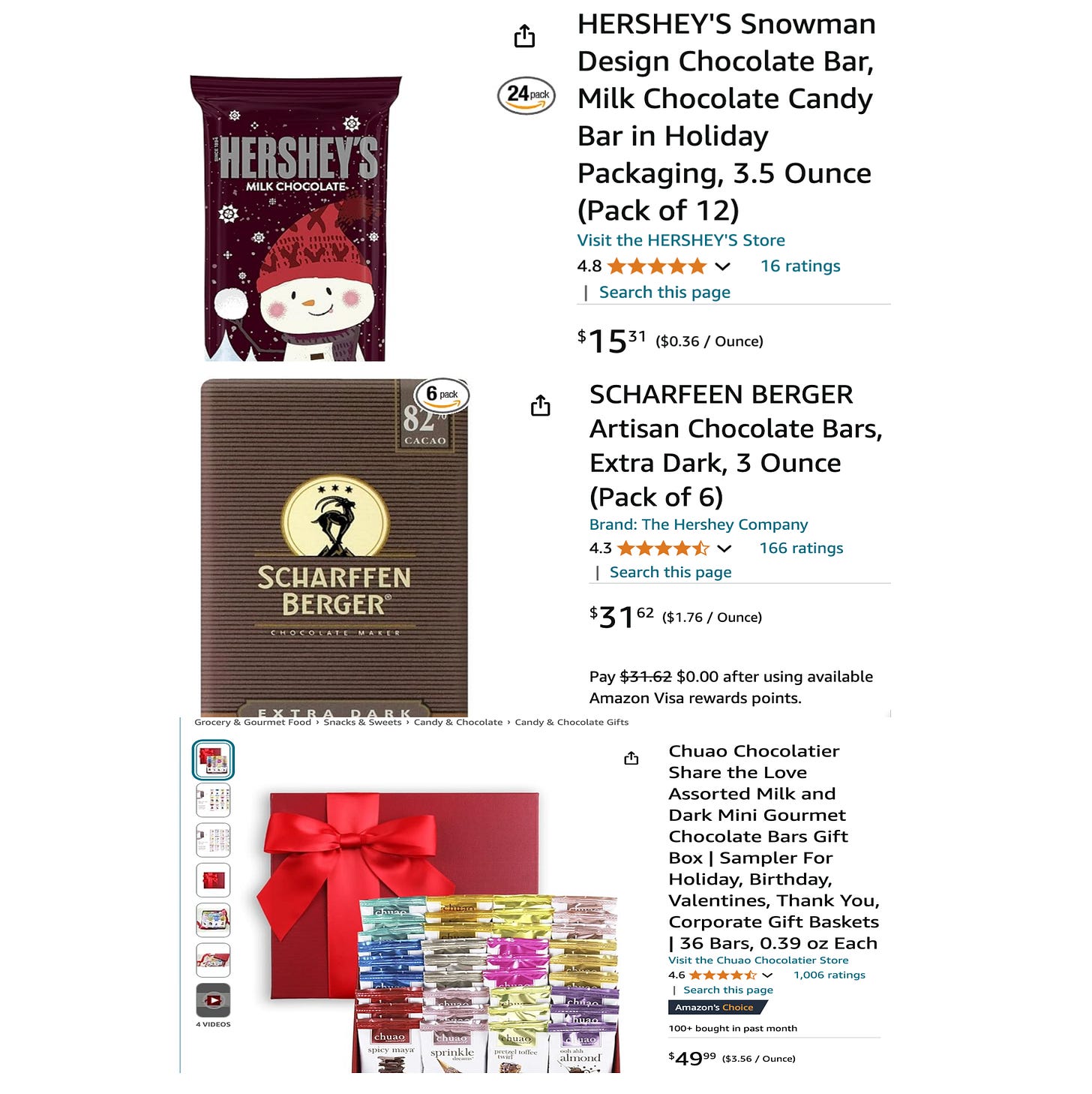

At the moment on <http://amazon.com> the chocolate bars that they are offering to sell to me range the gamut from a cost of $0.36/ounce to $3.56/ounce—a price-per-ounce span of ten:

I assure you that the bottom item, at ten times the price per ounce, is, indeed, consumed as a luxury, with attention to terroir and to the underlying Venezuela chocolate flavor protocol.

But then isn’t the global wine market divided the same way?

“Attention to terroir” and “Two-Buck Chuck” do not usually go together in the same sentence, after all…

When Alicia Kennedy writes:

there’s no reason why chocolate—all chocolate—shouldn’t be understood as a luxury, with diverse expressions of cacao terroir named, respected, discussed. But that only happens in the smallest of forums, and it’s mocked in the general culture to care about such things…”,

the words should and all seem to carry particular force.

Should. Is she saying that everybody, when they buy chocolate, should only buy the bottom product and not the top—and thus buy only 1/10 as much for their chocolate-buying dollar?

All. Is she saying that Hershey $0.36/ounce chocolate bars should simply not be sold here, under the moon?

Suppose all this were to happen within our current framework. Suppose we shifted all of cocoa and chocolate into the sphere of true luxury commodity production. And suppose we were in the process able to raise the share going to the grower from 1/8 to 3/8. And suppose that total spending on chocolate were to stay the same. We would then have three times as much money flowing to growers. But we would cut production to 1/10 of its current level: only 1/10 of those currently growing chocolate would then be able to do so. Those lucky cocoa-farming families would on the average make not $6,000/year but instead $180,000/year—an income that would place them well in the global upper-middle class as luxury-good producers.

But what would the other 9/10 of our current cocoa farmers then go and do? And even though three times as much money were flowing to cocoa farmers, would it indeed be a better world in which only 1/10 as much chocolate were produced—even if it were much higher in quality than the overwhelming bulk of the chocolate we see around us?

And do note that right now the Hershey corporation was very happy —before it spun out Scharffenberger to private equity—having one factory that produces chocolate selling at $0.36/ounce, and another one that produces chocolate selling at $1.76/ounce—five times as much—and letting people choose which to buy.

Camila Marcias writes not of making all chocolate production luxury production, but rather of:

decoupling… cocoa prices from… commodity exchange… set[ting]… them based on production costs, ensuring a living income for farmers…

It is not clear to me how this is supposed to work. In the absence of commodity exchange and its accounting principles, presumably cocoa-growers will receive what they deserve to have as income, and the price and quality of chocolate will be set at whatever is appropriate for consumers to pay—or perhaps a (high quality) chocolate ration will be distributed from government warehouses. Camila Marcias seems to think that this is unproblematic—that our current reliance on exchange is “colonial”—and that this is unproblematic because the current arrangement of production and distribution is unfair, with:

“smallholder… [growers] receiv[ing] a small fraction of the financial value, while a few large companies capture most of the profit… [and] millions of consumers enjoy the final product…

It is clear to her that the “corporations”should receive nothing. But that is only 7% of the use-value of current chocolate production: far from enough.

Are consumers to pay more and receive less than their $130 billion/year of consumer surplus? Are the incomes of the other workers in the chocolate value-chain to be reduced—their $97 billion/year is the bulk of the current commodity-exchange money flow? Is the government to make up the slack, and if so by taxing whom, and how much?

Three things clear to me:

The chances are very low that any cocoa-growing country is going to use public tax money to allow its COCOBOD to pay cocoa growers more than the world market price for cocoa. Rather, the reverse: cocoa exports are seen as a source of revenue that the government can use for its other purposes, be they economic development, political coalition maintenance, or simply a nice lifestyle for those who are at the levers of state power, plus well-paying middle-class jobs for their relatives.

The chances are very low that the assembled cocoa-producing countries of the world will be able to pull an OPEC. The major world cocoa producers are, roughly, Côte d’Ivoire (34%) and Ghana (17%) (with Cameroon and Nigeria also at 4% each), Indonesia (10%), Ecuador: (5%), Brazil: (4%), Peru: (2.5%), Dominican Republic: (1%), and Colombia (1%), with other countries outside the top ten at 17.5%:. The West Africans with 59% are not enough to set and hold a price peg by themselves given the possibility of extending cocoa production in its original Latin American heartland and in Southeast Asia.

It greatly sucks—it has long greatly sucked, since the beginning around 1870 of full globalization it has greatly sucked—to be the producer of a primary product in elastic supply but in inelastic demand. Mole aside, chocolate is, worldwide, a desert food. Elastic potential supply plus inelastic demand means that in a competitive market economy the overwhelming bulk of surplus goes to the (largely global north) consumers.

This is, of course, unfair and unjust—that cocoa growers earn so little while rich cocoa consumers enjoy chocolate so much. To repeat myself; as First Economist Adam Smith wrote back in 1776:

Servants, labourers, and workmen… make up the far greater part of every great political society…. No society can surely be flourishing and happy, of which the far greater part of the members are poor and miserable. It is but equity, besides, that they who feed, clothe, and lodge the whole body of the people, should have such a share of the produce of their own labour as to be themselves tolerably well fed, clothed, and lodged…

The economist’s recommended cure is successful economic development in cocoa-producing countries: have a developmental state that can guide the Ecuadorian economy the way that Deng Xiaoping’s state did in China.

Then, within a generation, Mars, Mondelez, Ferrero, Hershey, Nestle, and Lindt and company will have to pay cocoa farmers much more because they will have other attractive options. Then Mars and company will have to deal with what the effects of this market force-induced rise in the price they must pay for cocoa turn out to be on the rest of their production-and-distribution network and on the viability of their business. But creating a competent and successful developmental state in Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Cameroon, Nigeria, Ecuador, Brazil, Peru: (2.5%), and Colombia (1%) has proved impossible. (Indonesia and the Dominican Republic are managing.)

The global-left answer is… what?

Turning chocolate into a luxury commodity by reducing cocoa production by 90% seems a non-starter. Above all, that would reduce the total use-value of chocolate from $250 billion/year to $121.3 billion/year: the market-value component would stay ta $120 billion, and since the wedge between consumer use-value and market value goes with the square of production, that wedge—consumer surplus—would fall from $130 billion/year to $1.3 billion/year. You may well not—you should not—like the way the $250 billion/year of current use-value is distributed. But it is very hard to see how if you cut that use value by more than a half you can reärrange the deck chairs in a way that even lets you claim that you have made a better world.

So if Alicia Kennedy’s gut does not lead us in a positive direction, what does?

On one level, the answer is: Fair Trade. Buy less cheap chocolate! And when you do buy chocolate, if you can afford it, buy Fair Trade from Chuao Chocolatier—It is better! It is great! And even though it is expensive, we are rich and fat, and so it is very good for us for our calories to be expensive!—(or Scharffenberger, if indeed they now walk the walk and do not just talk the talk). Regard every act of commodity exchange you engage in not as something in which you are clear once the commodity and the money have been exchanged. Rather, regard every act of commodity you exchange in as creating a permanent sociological-nexus gift-exchange relationship, one in which you are under an obligation to exert yourself to do what you can to improve the life of the person to whom you are now tied, as they have given you this wonderful gift by growing the cocoa that is in these Guittard dark chocolate baking chips, and the small share of the money you paid that they received is really too little to make you properly square.

On a second level, be mindful.

Those are, I think, appropriate individual-level answer.

But it is not the system-level answer. What is the left’s system-level answer?