HOISTED FROM THE ARCHIVES: Department of "Huh!?!?!?!?!?!?": Monetary Policy Falsely Claimed to Be Market Manipulation

Paul Krugman, David Glasner, Miles Kimball, & Mike Konczal address the puzzle of John Taylor; from 2013-02-02: what is wrong with John Taylor’s claim that the Federal Reserve’s using monetary policy to push the market equilibrium price where it wants it to go is the same thing as a rent-control board keeping the administered price away from the market equilibrium price; David Glasner wins by calling John Taylor “thoroughly post-modern”, which is not a good thing as Glasner means “post-truth”…

The Puzzle of John Taylor: Department of “Huh!?!?!?!?!?!?” Weblogging

Paul Krugman takes his cut:

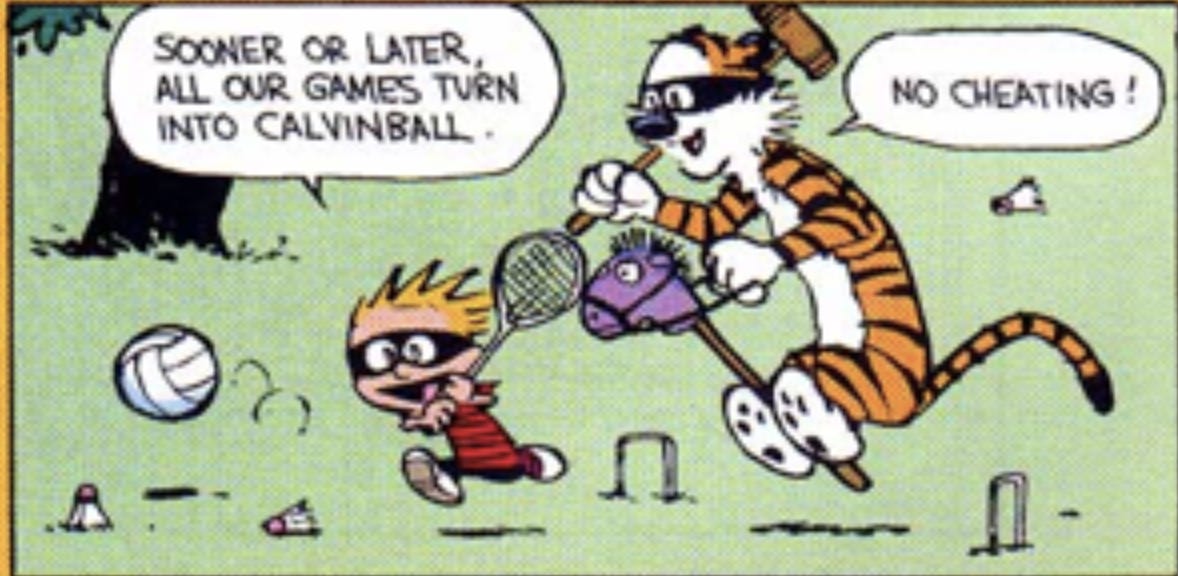

Calvinist Monetary Economics: Aha. In his latest op-ed, John Taylor comes out as a full-fledged monetary Calvinist. No, not a disciple of John Calvin, the preacher — a disciple of Calvin of Calvin and Hobbes…. Mike Konczal felicitously made that analogy to discuss the people who were calling for a rise in interest rates despite high unemployment and low inflation — a group at the time exemplified by Raghuram Rajan. For those who don’t read the classics, Calvinball is a sport in which you change the rules whenever you feel like it, very much including in the middle of games. Back then the tight-money types were inventing new and peculiar principles of monetary policy on the fly; it was obvious that they were looking for some reason, any reason, to justify a rise in rates, because, well, because.

Now Taylor is doing the same thing. He claims that he can show that the Fed’s low-rate policy is actually contractionary, using “basic microeconomic analysis”. Actually, as Miles Kimball points out, he’s committing a basic microeconomic fallacy — a fallacy you usually identify with Econ 101 freshmen early in the semester…. Taylor argues that low rates engineered by the Fed are just like a price ceiling that reduces the supply of loans, and therefore reduces overall lending. Wow. No, the Fed’s interest rate target isn’t a price control; there is no legal or other restraint on the rates lenders can charge. The Fed is driving down interest rates, or equivalently driving up the price of bonds, by buying bonds; I can’t think of any kind of economic analysis in which that would reduce the quantity of bonds sellers end up issuing, that is, the amount of borrowing (and lending) in the economy. It’s just bizarre, and bears no resemblance to anything a clearly-thinking economist would say.

David Glasner takes his cut:

John Taylor, Post-Modern Monetary Theorist « Uneasy Money: n the beginning, there was Keynesian economics; then came Post-Keynesian economics. After Post-Keynesian economics, came Modern Monetary Theory. And now it seems, John Taylor has discovered Post-Modern Monetary Theory…. Scott Sumner tried to deconstruct Taylor’s position, and found himself unable…. How post-modern can you get? Taylor is annoyed that the Fed is keeping interest rates too low by a policy of forward guidance…. [T]he alert reader is surely anticipating an explanation of why forward guidance aimed at reducing the entire term structure of interest rates, thereby increasing aggregate demand, has failed to do so, notwithstanding the teachings of both Keynesian and non-Keynesian monetary theory. Here is Taylor’s answer: “At the very least, the policy creates a great deal of uncertainty. People recognize that the Fed will eventually have to reverse course. When the economy begins to heat up, the Fed will have to sell the assets it has been purchasing to prevent inflation…”

Taylor seems to be suggesting that, despite low interest rates, the public is not willing to spend because of increased uncertainty. But why wasn’t the public spending more in the first place, before all that nasty forward guidance? Could it possibly have had something to do with business pessimism about demand and household pessimism about employment? If the problem stems from an underlying state of pessimistic expectations about the future, the question arises whether Taylor considers such pessimism to be an element of, or related to, uncertainty? I don’t know the answer, but Taylor posits that the public is assuming that the Fed’s policy will have to be reversed at some point. Why? Because the economy will “heat up.” As an economic term, the verb “to heat up” is pretty vague, but it seems to connote, at the very least, increased spending and employment. Which raises a further question: given a state of pessimistic expectations about future demand and employment, does a policy that, by assumption, increases the likelihood of additional spending and employment create uncertainty or diminish it?…

A more interesting reason is provided when Taylor compares Fed policy to a regulatory price ceiling…. When economists talk about a price ceiling what they usually mean is that there is some legal prohibition on transactions between willing parties at a price above a specified legal maximum price. If the prohibition is enforced, as are, for example, rent ceilings in New York City, some people trying to rent apartments will be unable to do so, even though they are willing to pay as much, or more, than others are paying for comparable apartments. The only rates that the Fed is targeting, directly or indirectly, are those on US Treasuries at various maturities. All other interest rates in the economy are what they are because, given the overall state of expectations, transactors are voluntarily agreeing to the terms reflected in those rates. For any given class of financial instruments, everyone willing to purchase or sell those instruments at the going rate is able to do so. For Professor Taylor to analogize this state of affairs to a price ceiling is not only novel, it is thoroughly post-modern.

Miles Kimball: Contra John Taylor:

Let’s turn to John’s most remarkable claim—the one that inspired my statement that his op-ed had “extraordinarily bad analysis.”… To the extent that forward guidance has bite, the Fed is promising to shift the demand curve for assets in the future and thereby get to a particular equilibrium interest rate. This is not at all like rent control. The right analogy is, say, New York City getting rents to come down by reducing making it easier to get a building permit, or by subsidizing the building of new apartments. The Fed is pushing asset prices up and interest rates up by a combination of buying assets now and promising to buy them in the future. There is a world of difference between a market intervention in which the government contributes to supply and demand and a price floor or ceiling…. The fact that the Fed acts by changing the equilibrium interest rate matters, because John’s claim that lowering the interest rate will reduce the quantity of investment would hold only if what the Fed is doing really did act like an interest rate ceiling that makes asset demand lower than asset supply. But what the Fed is doing is adding to asset demand…. Anyone issuing selling assets to raise funds can sell them much more easily when demand for assets is strong…. [I]t leads to very bad policy analysis if Fed asset purchases and promises of future asset purchases are mischaracterized as the kind of interest rate ceiling that leads to disequilibrium.

And Mike Konczal:

Rajan Plays Calvinball on Monetary Policy: friend pointed out that post-crisis conservative economists talking about monetary policy in general, and QE2 specifically, is like watching a game of Calvinball – they appear to be making up the rules and the specifics of how to score points in the debate on the fly…. Rajan, who previously argued that there was something special about being at zero that made the market go sideways… has gone from creating arguments that the zero-bound encourages too much speculation to a morality play. There’s Ben Bernanke, a WWI general pushing soldiers over the trenches. Inflation taxes producers and subsidizes spenders is the main result. Would the phrase that inflation taxes hoarders, provides incentives to do transactions, relieves the debt burden of the past and balances the relationship between creditors and debtors (and debt and the entire economy) be equally acceptable?

There’s a reason people either look to employment and inflation or a level or inflation target to determine what is the best course of action in monetary policy. It’s so that the goal of monetary policy is clear. It’s not about rewarding the good people and punishing the wicked, it’s about stabilizing growth, prices and maximum employment without overheating the system or letting it choke to death from a lack of oxygen…