HOISTED FROM THE ARCHIVES: The Late-Antiquity Pause, & the so-Called “Bright Ages!”

From January 12, 2022: again, pulling something out of an earlier version of this weblog’s multi-subject posts so that I will be able to find it again more easily in the future…

‘In 572, after the capitulation of Pavia… King Alboin was assassinated… by his wife Rosamund and her lover, the noble Helmichis…. They were forced to flee together to the Byzantine territory before getting married…. Later in 572, the thirty-five dukes assembled in Pavia to hail king Cleph…. He, too, fell victim to regicide in 574, slain by a man… who perhaps colluded with the Byzantines. Following Cleph’s assassination… for a decade dukes ruled as absolute monarchs in their duchies…. In 584 the dukes agreed to crown King Cleph’s son, Autari…. He assumed, like the Ostrogoth Kings, the title of Flavio, with which he intended to proclaim himself also protector of all Romans in Lombard territory….

Autari… marr[ied] a princess, Theodelinda, from the Lethings dynasty… a line of descent from Wacho, king of the Lombards between 510 and 540, a figure surrounded by an aura of legend…. Autari died in 590, probably due to poisoning…. The young widow Theodelinda… [then] chose the heir to the throne and her new husband: the Duke of Turin, Agilulf…. A rebellion among some dukes in 594 was preempted…. [A] new organisation of power, less linked to race and clan… more to land management…. The Lombard kingdom… gradually lost the character of a pure military occupation…. Agilulf made some symbolic choices aimed at… gaining credit with… Latin[s]…. The ceremony of ascension to the throne of his son Adaloald in 604, followed a Byzantine rite…. Gratia Dei rex totius Italiae, “By the grace of God king of all Italy”, and not just Langobardorum rex, “King of the Lombards”…. Strong pressure, particularly from Theodelinda, to convert the Lombards….

After the death of Agilulf in 616, the throne passed to his son Adaloald, a minor. The regency (which continued even after the king passed into majority) was exercised by… Theodelinda, who gave command of the military to Duke Sundarit…. A civil war broke out in 624, led by Arioald, Duke of Turin and Adaloald’s brother-in-law (through his marriage to Adaloald’s sister Gundeperga). Adaloald was deposed in 625 and Arioald became king…. Rivalry between the Arian and Catholic factions…. The Arians also opposed peace with Byzantium and the Papacy and integration with the Romans… At [Arioald’s] death… Queen Gundeperga had the privilege to choose her new husband and king. The choice fell on Rothari, the duke of Brescia and an Arian…

That is from Wikipedia: Kingdom of the Lombards <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_the_Lombards>.

A Bright Age, indeed, was Italy around 600 under the Lombards!

As you can see, Matthew Gabriele & David M. Perry (2021): The Bright Ages: A New History of Medieval Europe (New York: Harper) <https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Bright_Ages/UgwiEAAAQBA> rubbed me rather the wrong way with its rather bizarre and tendentious claims that:

One premise: Rome did not fall. Things continue and things change…. Cities never vanish but they do shrink, both in population and in importance, as people find new ways to organize political, economic, and cultural life in seeking stability. That stability comes with innovative ways of thinking about God… sparking a fire that will nourish a blossoming of intellectual and literary life…. But then circles turn again…. Connections between regions that were never severed did stretch and attenuate… creating the conditions for a medieval Italian poet to follow in the footsteps of a late Roman empress. Welcome to The Bright Ages…

And yet, in ex-Roman Italy, we have: a pure military occupation for the first two generations, “strong pressure” to convert people to Christianity (and we know how that goes), kings trying to convince a subject population that they are more than barbarian bully boys by claiming that they are of Rome’s Flavian clan—that is, kin in some sense to the late-00s Roman Empire Titus Flavius Vespasianius (as claiming status as kin to a Roman princeps et imperator of the past was a thing to conjure with)—the near-collapse of urban life, a substantial reduction in the ability of the rural population to purchase cheap mass-produced conveniences that make life comfortable from urban workshops, possibly a reduction in exploitation to feed an upper class, certainly a loss-of-status as small independent farmers who can no longer trust in the pax Romana. What was the alternative, then? To go to the local bullyboy, and put yourself in bondage as a colonus or a villain:

By the Lord before whom this sanctuary is holy, I will to [NAME] be true and faithful, and love all which he loves and shun all which he shuns, according to the laws of God and the order of the world. Nor will I ever with will or action, through word or deed, do anything which is unpleasing to him, on condition that he will hold to me as I shall deserve it, and that he will perform everything as it was in our agreement when I submitted myself to him and chose his will…

(Parenthetically, the last person to conjure with names, attempting to gain authority by claiming kinship with a Roman princeps et imperator from before the Dark Ages was Albert Frederick Arthur George Windsor, George VI, who called himself “Caesar of India” up until 1947.)

Starting 50,000 years ago, we have our guesses—my guesses—of the level of average annual real income per capita y, measured in today’s dollars, and of the human population P. Define the level of human technological prowess H as equal to y times the square-root of P. Why is H proportional to y? That is just a definition, a normalization: technology enables and enhances a finer and more productive human division of labor, and so it makes sense to define H so that a counterfactual globe with the same population and resources but twice as high a living standard y would require twice as great a level of technology H to support that higher living standard. Why the square-root of P? Well, if we defined H = yP, we would be implicitly saying that individual human hands, eyes, brains, and mouths were of no account: that to support twice the population at the same living standard would require twice the technology. That makes no sense. If we defined H = y we would implicitly be saying, to the contrary, that national resources were unnecessary and unproductive. That also makes no sense. The square-root seems a reasonable compromise.

Thus from our guesses as to average real income y and global population P, we can construct guesses as to H: the value of the stock of useful and productive technological ideas about the manipulation of nature and the organization of humans known by the time-binding anthology intelligence that is the human race. And we can construct guesses as to h, the proportional growth rate of the value of that as stock.

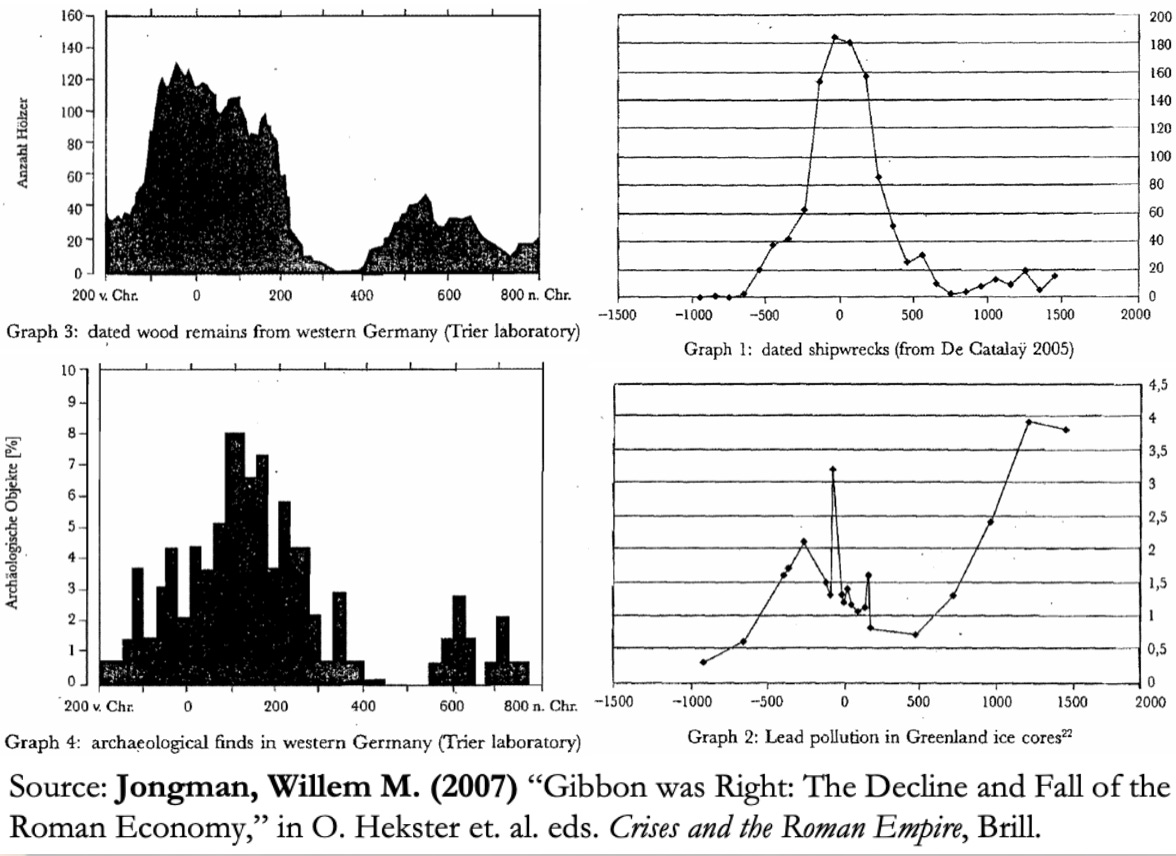

When we do this, we see that h has been 2.2%/year for a century and a half in our age of Modern Economic Growth; that it was less than a quarter as much—0.45%/year—for the Industrial Revolution Age century before that; that it was a third of that—0.15%/year—for the Imperial-Commercial Age from 1500-1770; that it was 2/5 of that—0.6%/year—for the High Mediæval Age from 800-1500; and that it was a quarter of that—0.015%/year—from the year 1 to the year 800. We see for the past 2000 years an upward march of the level of technology H—although for the first 1500 years this upward march is diverted to compensate for increasing resource scarcity as greater human numbers mean smaller farm and grazing-land sizes per person—at an increasing pace.

But then, as we look back from the year 1 to the year -1000, we see something odd. Human population increased by only 30% from 1 to 800. (That is what drives our h of 0.015%/year.) But in the 1000 years before the year 1 human population more than tripled. (That gives us a Classical Antiquity Age h of 0.6%/year, equal to what we saw from 800 to 1500.)

So what happened in the years up to 800? It was not technological regress (though there was some: loss of the ability to make cement, for example). The world population was 30% larger and thus people were managing on 30% smaller farm sizes than they had back in the year 1 But the pace of innovation appears to have fallen to ¼ of what it had been in the pre-1 years of Classical Antiquity. And there was a definite loss at the eastern and western provinces of Eurasia of the ability to invest in building and maintaining physical capital. It was most pronounced by far at the western edge of Eurasia, in the Roman Empire, and especially the western Roman Empire.

But you can, if you squint, see a fall in the indexes we have of long-distance trade and durable construction across the supercontinent.

The rest of the pattern of human history would have suggested an increasing h from 1-800—perhaps to 0.1%/year or so—and a world population of 375 million or so. Such human numbers not reached in our history until the eve of the 1346-8 Black Death.

It seems to me to try to write human history without taking note of this… let’s politely call it “the Late-Antiquity Pause”—that is not just to present Hamlet without the prince, but without the king, queen, advisor, lover, and best friend as well…