Gunpowder-Empire Fiscal Legibility & State Development: Economic History/Political Economy Seminar

Francisco Garfias & Emily A. Sellars: “Fiscal Legibility & State Development” :: 2024-03-04 12:30 PST :: Philosophy 223, U.C. Berkeley…

The Viceroyalty of New Spain in 1550:

one viceroy, installed in the Palacio Nacional on the east side of the Zócalo in Ciudad de México.

10,000 or so Castilians (or people calling themselves pure-blooded Castilians.

four million ro so of los Indios (and dropping).

with the Castilians running perhaps the purest form of a gunpowder-empire domination-and-exploitation machine.

Perhaps 500 or so of the more senior adult-male Castilians are sent out with their guards, horses, and muskets as encomenderos, to collect the head tax (plus a little more) and remit it to the viceroy. A good many more local caciques collect the head tax and send it on themselves, hoping that if they are agreeable they can avoid their tribes being turned into someone’s encomienda. To try to reduce the chances that any one encomendero decides to simply plunder all he can and not also rule his encomienda as a deputy of the viceroy, it is heavily implied that the encomienda is yours for life, and that if there are few enough complaints from los Indios your son may well succeed you in what might well someday become your family’s latifundia.

But there is high-level discontent in the Palacio Nacional alongside the Zócalo. The encomenderos are living well—too well. And it would be a big black eye for the viceroy should any one or—horrors—many of them decide that they no longer need to remit the head tax to Ciudad de México to be sent on to Madrid when neither the Ciudad de México nor Madrid does anything for them. So there is a substantial desire to turn encomiendas into corregimientos, replacing long-term encomenderos with short-term corregidores on fixed—low—salaries.

The fear, however, is that a short-run limited-term corregidor will engage in maximum plunder and so devastate the district, and then be gone back to Spain with his ill-gotten gains before what he is doing is known alongside the Zócalo. As long as the viceroy has literally no idea whether low head-tax remittances arise because of crop failure (so los Indios cannot pay) or from unusually high rates of theft, better to leave things in the hands of an encomendero. An encomendero at least has a powerful incentive to be a long-run rather than a short-run stationary bandido, and so not shear the sheep so closely that they freeze in the winter.

But over time it happens that viceroys learn more about what head-tax revenues ought to be, and so seek to centralize more and more—to turn encomiendas into corregimientos.

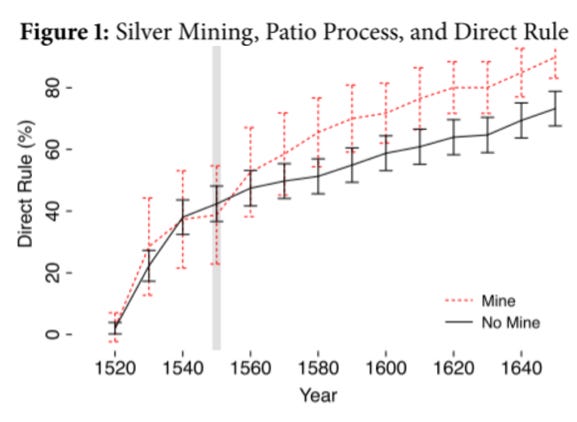

This is what Franciso Garfias and Emily Sellars track in their “Fiscal Legibility & State Development: Theory & Evidence from Colonial Mexico”. Forty percent of districts are administered as a corregimiento by 1550, and more than seventy percent by 1650:

But, as this process proceeds, something interesting happens.

It starts in 1554 with Bartolomé de Medina in Pachuca. He invents and installs the “Patio Process” for extracting silver from ore. Before, you extracted silver from ore using lots of lead and firewood—and labor. Afterwards, in the Patio Process, you would:

grind the silver ore to a fine powder,

mix it with salt, water, copper sulfate, and mercury

spread the mixture out over a large, flat open space—the Patio—in a shallow layer,

have horses (or mules) tread over the mixture,

thus amalgamating the silver with the mercury,

and then collect and heat to vaporize the mercury,

leaving behind near-pure silver.

You could do this. If you could get get the mercury.

And then the viceroy and his official the Alcalde de Minas could watch where the mercury went, and thus figure out what the king’s share of the silver from each mine the mercury went into ought to be.

All this about mercury and silver mining and Bartolomé de Medina and the Alcalde de Minas is reasonably well-known, at least among those who study the gunpowder-empires of Latin America.

But Garfias and Sellars have noted something in addition:

To get workers into mines in Mexico as the coming of the Patio Process expanded the ease of extraction, you had to pay them (as opposed to in Peru, where you simply enslaved them). Thus people—people paid in silver—flowed into mining districts to work in the mines. Then, as they spent their silver, more people flowed in to make things for the miners. Mining districts into which a lot of mercury was flowing so became much more prosperous.

Thus the flow of mercury into a district thus gave the viceroy, through the reports of his Alcalde de Minas, extra information about how prosperous the district was—and thus extra information about how much head-tax revenue ought to be remitted to Mexico City.

And what Garfias and Sellars note is this: In the aftermath of the 1554 Patio Process invention, viceroys were more willing to put mining districts into corregiemento, even though there was no direct connection between what was happening in the mines on the one hand and what the encomendero or corregidor could do or was doing. They hypothesize that the ability alongside the Zócalo to compare head-tax flowing in with mercury shipments sent out gave viceroys and their officials more confidence that they could spot a corregidor who was slacking-off and too corrupt in time, and thus more of a willingness to push forward on administrative centralization. Hence the dotted red line in the figure above: the transition of mining districts from encomienda to corregimiento accelerates in the generation after the coming of the Patio Process to Mexico silver extration, while the transition slows down in non-mining districts.

Reference:

Francisco Garfias & Emily A. Sellars. 2024. “Fiscal Legibility & State Development: Theory & Evidence from Colonial Mexico”. New Haven: Yale University. <https://economics.harvard.edu/sites/hwpi.harvard.edu/files/econ/files/emily_sellars_-_yale_0.pdf?m=1677859827>

Francisco Garfias & Emily A. Sellars: Fiscal Legibility & State Development: Theory & Evidence from Colonial Mexico: ‘Rulers lack[ing] information… cede autonomy…. As information quality improves, rulers… tighten control… and establish more direct state presence. Centralization encourages additional investment in improving fiscal legibility, leading to long-term divergence in state development…. A technological innovation that dramatically improved the Spanish Crown’s fiscal legibility in colonial Mexico: the discovery of the patio process to refine silver…. Political centralization differentially accelerated in affected districts, that these areas saw disproportionate state investment in informational capacity.…

Replacing encomiendas with corregimientos… The patio process… mercury amalgamation to extract pure silver from mined ores…. Because mercury was only produced at scale in a handful of locations worldwide—and not in Mexico—the Crown was able to institute and enforce a monopoly over the sale and distribution of this key input. This gave central authorities a direct and reliable new way to observe…. The sudden increase in fiscal legibility in mining districts led to an acceleration in political centralization. The proportion of encomiendas that transitioned to direct rule was around 8–13 percentage points higher in mining relative to non-mining districts and relative to the period before the patio process had been discovered….

Because both fiscal legibility and political control were higher in affected areas before office selling became commonplace, the Crown had less to gain from outsourcing administration of these districts to private actors, which insulated these areas from the negative consequences of office selling on rent extraction and official corruption… <https://economics.harvard.edu/sites/hwpi.harvard.edu/files/econ/files/emily_sellars_-_yale_0.pdf?m=1677859827>