Affirmative Action: A Primer, & A Finger Exercise

In which I hoist my Woke Freak Flag, for the edification of the public…

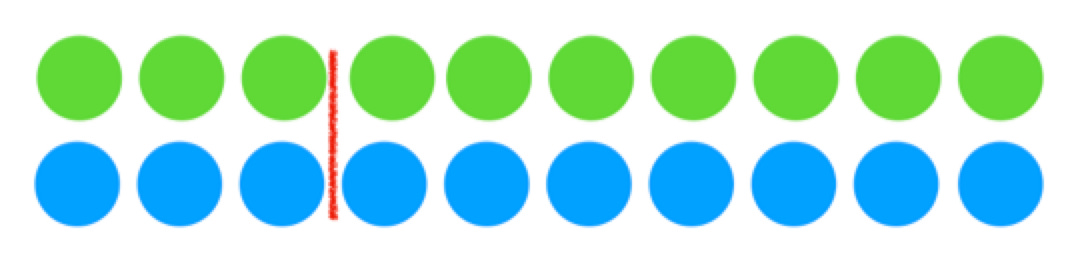

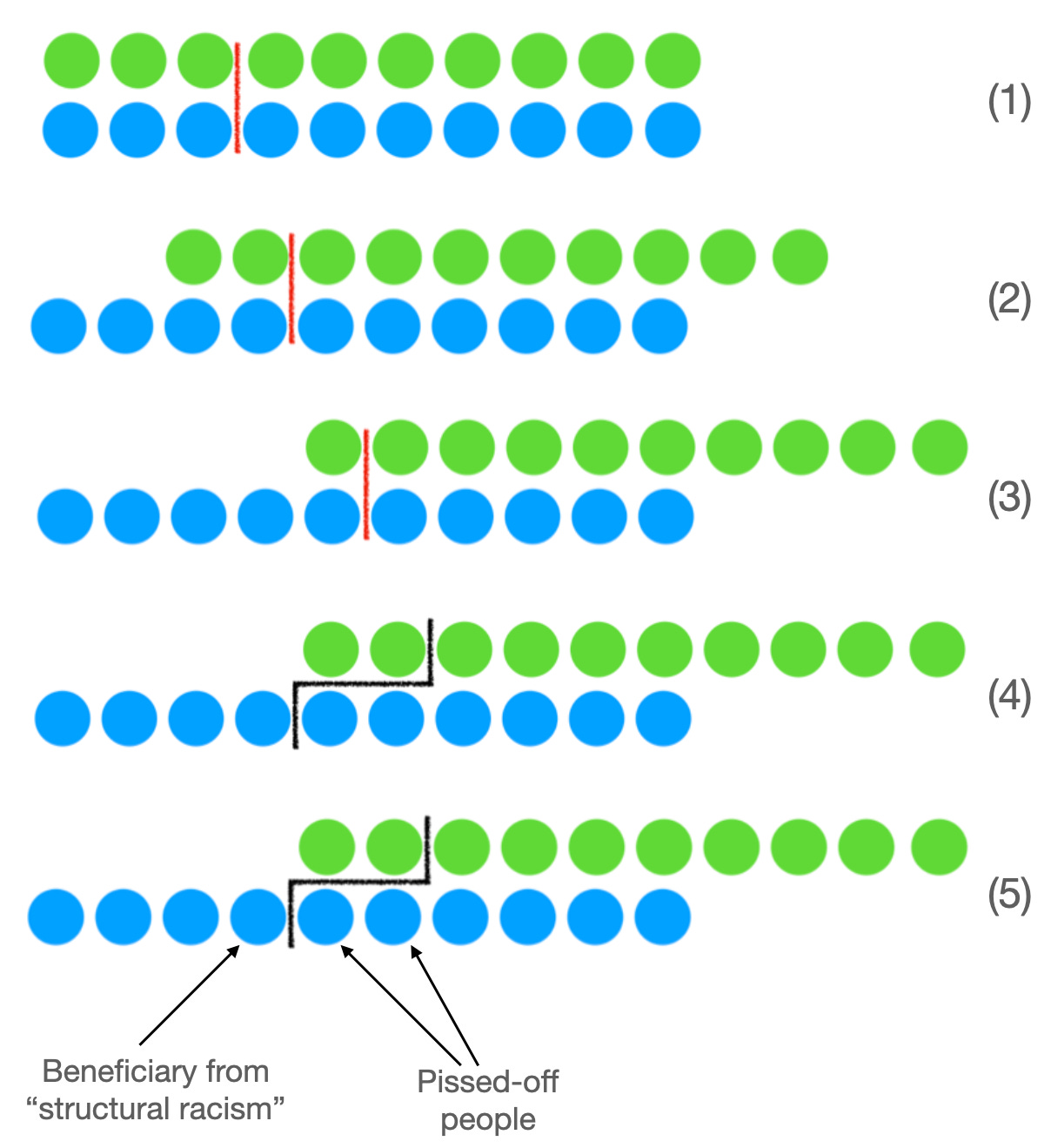

Start out with a society with two “races”, greenies and blueies, and with raw talent that can be developed into a capability to do the job that is equally distributed across races. Some people in each race with more raw talent than others. Like so, with raw talent increasing as you go from right to left:

In this situation, a good and well-working meritocratic system to choose six people for the slots that focused only on getting the best people who can do the job most effectively would pick three blueies and three greenies—those to the left of the red line.

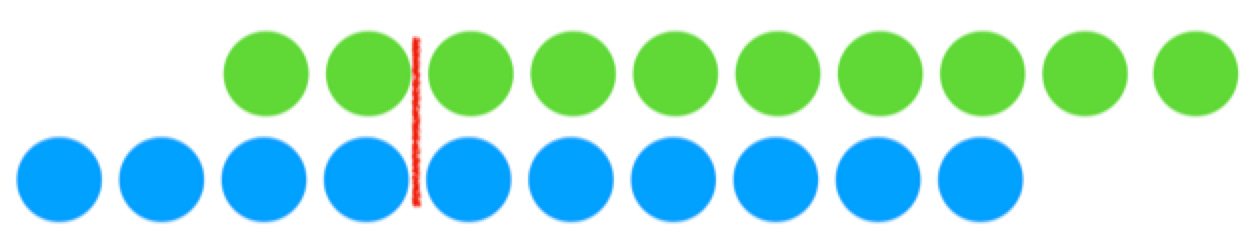

But suppose society is afflicted by structural racism: it discriminates against the greens by depriving them, relatively, of the resources, education, and training they need to learn how to be able to do the job, to develop raw talent into capability. The end result is that the top-talented greenie winds up only as capable of doing the job as the third-talented blueie, and so forth, like so:

In this situation, a good meritocratic system that focused only on getting the best people who can do the job most effectively and that is limited to choosing six people for the slots would pick four blueies and two greenies—those to the left of the red line. If the jobs are desirable ones to have—and they may well be—such a selection would be, in a sense, unfair: there is a greenie who does not get chosen even though the fact that their talent was not developed to the fullest is not their fault but arises because of the structural racism; there is a blueie who gets chosen even though their raw talent would have been seen as inadequate in a society without structural racism.

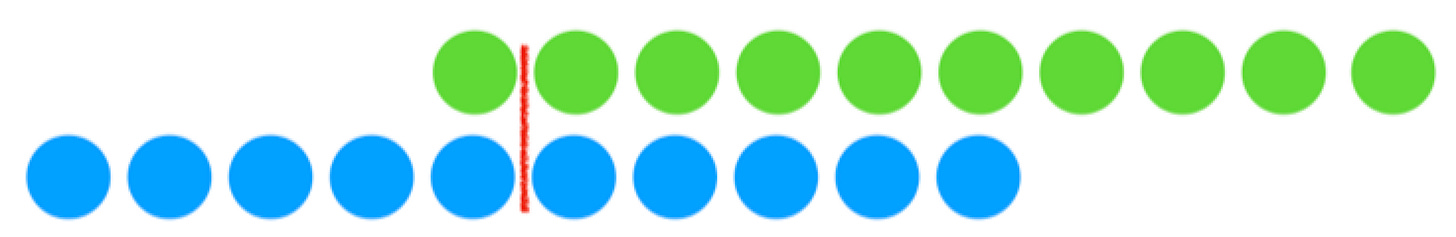

Now, suppose, second, the society has a test, a “meritocratic” test for whether people are good at doing the job. Unfortunately, the test is also structurally racist: it further discriminates against the greens. The end result is that the top-talented greenie—as capable of doing the job as the third-talented blueie—is only ranked by the test as equal to the fifth-talented blueie, and so forth, like so: test

In this situation simple giving the job to the six high scorers gets us five blueies and one greenie. Two of the blueies are then, if the job is a desirable one to have, beneficiaries of structural racism—one because the greenie who ought to have had the slot on the basis of raw talent was not allowed to develop that talent into a capability, and the second because even though the greenie who ought to have had the slot on the basis of raw talent did develop that talent into a capability, the structural racism in the test kept that from being recognized. And, of course, those two greenies are the victims of structural racism here.

Picking those to the left of the red line—picking the five blueies and the one greenie who scored highest on the test—is not the right thing to do if you want to choose the people to do the job best. Greenie #2, even though their test score is only equivalent to that of blueie #6, has the capability to do the job as well as blueie #4 and distinctly better than blueie #5.

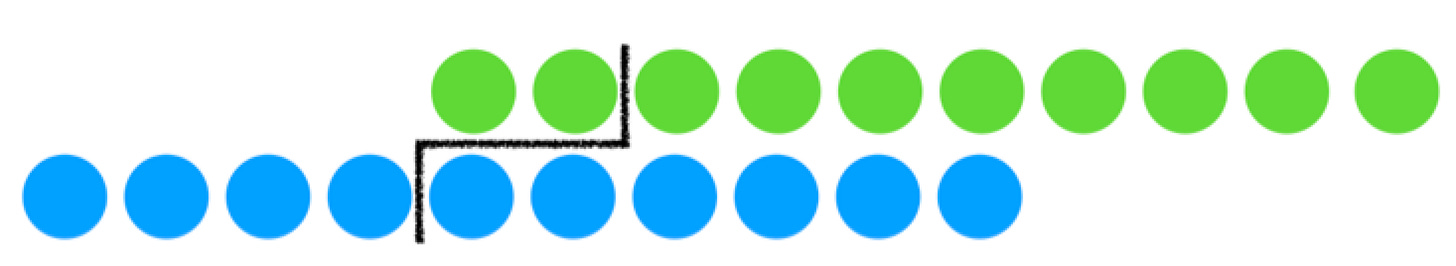

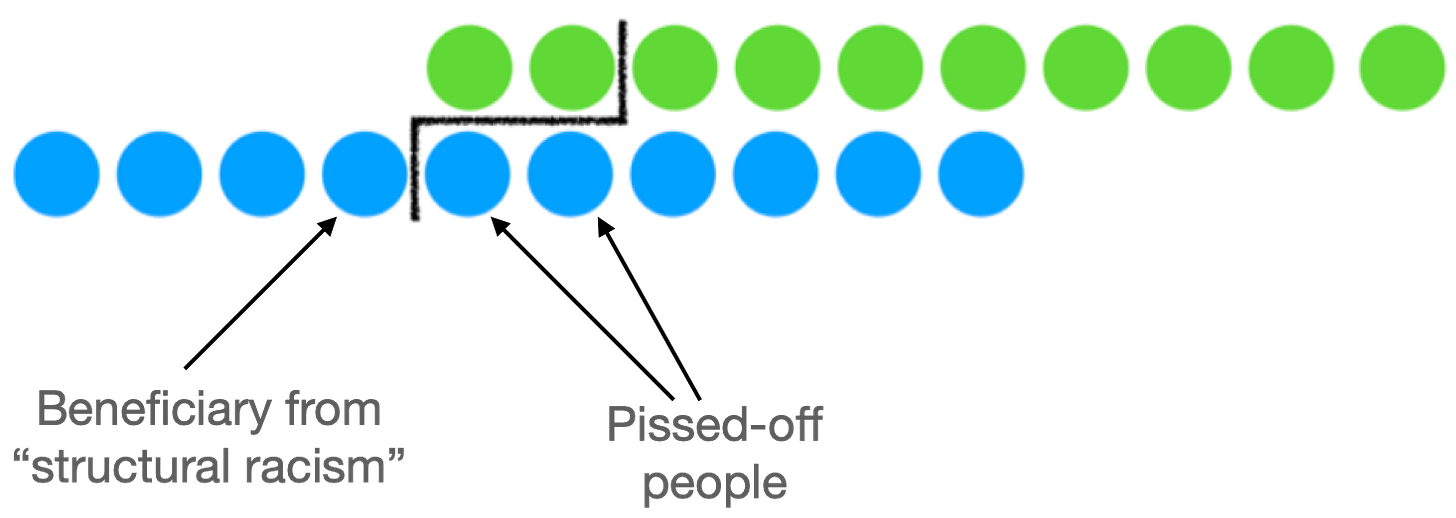

What one would want to do—if one were interested only in getting the job done as well as possible—is to pick six people like so: those to the left of the jagged black line:

That gets the job done as well as possible, given that structural racism has prevented the most talented individuals in the greenie population from fully developing their raw talent into their full potential capability to do the job, and given that the test is underpredicting the true capability to do the job of greenies.

But if we choose those to the left of the jagged black line, we now have more complicated situation in terms of perception than just one or two blissful and ignorant blueie beneficaries of structural racism. Now we do have one blissful and ignorant blueie beneficiary of structural racism. And we also have two really pissed-off blueies—pissed off because they falsely believe that their opportunity that was rightfully theirs by the rules of the meritocratic system has been stolen from them by SOCIAL JUSTICE WOKEISM:

The two really pissed-off blueies do not understand the situation any better than—in fact, they understand it somewhat worse than—the blissful, ignorant blueie ranked #4, who thinks they have “earned” their place, rather than gotten their place because of the handicap structural racism has imposed on the four greenies with equal or more raw talent.

The system is in fact doing its best to find the people to do the job, and the balance of evidence, given the imperfections of the “meritocratic” test as a measure of who actually has the capability chops to do the job best, is that blueies #5 and #6 have not in fact “earned” anything at all.

Good luck getting them to understand that.

They will not understand that the system is working. And they definitely do not understand that in a truly good society they would never have been on the short list at all. “Born on third base; thinks he hit a triple”, as Texas Governor Ann Richards said of George W. Bush.

To recapitulate, we have (1) the distribution of talent, (2) the actual capabilities of being able to do the job well after structural discrimination has wrought its damage, (3) a noisy “meritocratic” test for capability that is also structurally racist, (4) the people who you should choose if you actually want the job done as well as possible, and (5) one smug blue guy who thinks he “earned” his position even though he owes it to structural racism, and two really pissed off white blue people who falsely see themselves as unjustly victimized by the reverse discrimination that is affirmative action.

To recapitulate: All assuming that the goal is to choose the right people to fill a relatively small number of the demanding jobs so that the job gets done in the best way possible:

Assume raw talent is evenly distributed across the group of which society is made. Then a good choice procedure would see people filling demanding jobs roughly in proportion to their numbers in the population.

Assume that society is structurally racist against the greenies. Then we should fix that—make equal opportunity, so that greenies with lots of raw talent have the same resources to build that talent into a capability to do the job well in the same way that blueies do. But, if not, we should then not be surprised to find that a good truly meritocratic choice of who should do the job finds itself overweighting the privileged blueies. That is, in some sense, an injustice if getting one of those jobs is an honor, a privilege, and a source of wealth. But it is price society must pay if its overwhelming lexicographic preference is to get the job done as well as possible.

But if society is structurally racist against the greenies in the allocation of resources your “meritocratic” test for capability to do the job is likely to be structurally racist against greenies as well. Hence simply allocating jobs to those with the highest test scores is a mistake.

Instead, to the extent you really want to get the job done, should take account of the structural racism in the test (but not the structural racism in the allocation of resources) in choosing the people to do the job.

But this is highly likely to cause strong grievances among the not-so-wise among the privileged blueies. Those who get the job only because structural racism has knocked down their competition do not recognize that fact, and think they got the job through their “merit”. Those who watch others, greenies, with lower “merit” test scores butt ahead of them in the line for the jobs are really pissed off, and cry about unfair reverse discrimination.

Now there are lots of issues we have not reached:

Any human group makes up an anthology intelligence. There are great potential benefits for an anthology intelligence to not have all of its subunits be near cookie-cutter copies of each other. Even if the test perfectly measures the individual capability to do the job, we should think about this.

There may be benefits for a younger and up-and-coming generation to have visible role models. Even if the test perfectly measures the individual capability to do the job, we should think about this.

There may be social solidarity benefits to demonstrating that upward mobility and opportunity is not a myth—that, as Napoleon said, every soldier, whether greenie or blueie, potentially carries a Marshall’s baton in their knapsack. Even if the test perfectly measures the individual capability to do the job, we should think about this.

There are incentivization reasons to reward people who work hard, but there are no incentivization reasons to reward people who do a good job if they were lucky enough that even a lazy-ass level of focus and diligence on their part produces good results. Should these scarce and demanding jobs be positions of honor, prestige, and wealth in the first place, so that people think there is a lot at stake in the choice and a lot lost when you do not get one of them? As C. Northcoat Parkinson observed, if you ever find that you have more than one qualified applicant for a job, you should conclude that you are paying too much.

Indeed, James Mirrlees would wonder whether those who are highly capable of doing a good job should be rewarded relative to the average at all—leisure is a normal good, and the leisure of the capable is an expensive thing for society to buy, hence perhaps the capable should be poor. Leave those who are less capable to boost the overall average utility of society by smelling the roses. Incentivization is relative to some baseline. Perhaps the baseline level of wealth of those with lots of raw talent should be very low, to give them the maximum incentive to develop their capabilities and then work extra-diligently to apply them if they want more than one meat meal a weak.

References:

DeLong, J. Bradford. 2021. “Against Meritocracy”. Grasping Reality, December 28.

Mirrlees, James A. 1971. “An Exploration in the Theory of Optimum Income Taxation”. Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 38, No. 2 (Apr.), pp. 175-208. <https://doi.org/10.2307/2296779>

Parkinson, C. Northcoat. 1957. “The Short List, or Principles of Selection”. In Parkinson’ Law: & Other Studies in Administration. Cambridge, MA: The Riverside Press. Pp. 45-58. <https://archive.org/details/parkinsonslawoth00park/page/n6/mode/1up>

Schaede, Ursula, & Ville Manki. 2023. “Quota vs Quality? Long-Term Gains from an Unusual Gender Quota”. <https://ursinaschaede.github.io/files/JMP_Schaede.pdf>

Sethi, Rajiv. 2021. “Notes on a Remarkable Finding from Finland”. Imperfect Information, October 31.