Morning Notes on December 19, 2023 on the Inflation Debate

Largely a clarification-of-thought exercise for my own benefit…

With adaptive expectations—inflation expectations for next year are what inflation has been in the past year—and with a Phillips curve slope of 0.4, unless you have favorable supply shocks it requires 2.5%-point years of excess unemployment above the natural rate in order to permanently reduce inflation by 1%-point.

That, I take it, was the framework that Larry Summers was using to analyze what was needed to control the post-plague reopening inflation.

He, in mid–2022, posited for his base case:

A natural rate of unemployment at 5%.

A reopening-inflation rate of 7% per year.

But associated with this only inflation expectations of 4% per year.

Hence to get inflation down to 2% would require elevating unemployment above 5% by a cumulative total of 5%-point-years, which could be accomplished, Summers said in mid–2022, by:

five years of unemployment above 5% to contain inflation—in other words, we need two years of 7.5% unemployment or five years of 6% unemployment or one year of 10% unemployment…. There are numbers that are remarkably discouraging relative to the Fed Reserve view…

Philip Aldrich of Bloomberg provided context:

Fed policy makers raised interested by 75 basis points on Wednesday [June 15, 2022], the biggest increase since 1994. In their accompanying outlook, they signaled they see inflation easing from above 6% today to below 3% next year and near 2% in 2024. The median forecast showed unemployment rising to 4.1% by 2024, from 3.6% in May…

And Summers then concluded:

The gap between 7.5% unemployment for two years and 4.1% unemployment for one year is immense. Is our central bank prepared to do what is necessary to stabilize inflation if something like what I’ve estimated is necessary?…

It would be – it was – only natural to wonder if 7.5% unemployment for two years was the price of getting inflation down from 4% to 2% per year, was that price worth paying?

The parry was and is: That logic will always apply. If markets were to fix on the idea that that logic is likely to apply, then next year’s inflation expectations would not be last year’s actual inflation but, rather, last year’s actual inflation plus 1%-point. Then in order to maintain stable inflation at any level the unemployment rate would have to be permanently elevated by 2.5%-points above the sustainable natural rate. That would be an absolutely catastrophic situation.

Now I need to stress one point here: LARRY SUMMERS’S FEARS WERE NOT STUPID. THOSE RISKS WERE REAL.

The Federal Reserve, however, moved quickly to deal with these fears.

Even though I was an advocate of raising interest rates late, fast, and far, I was surprised by how fast and far the Federal Reserve moved once it concluded that it had bought sufficient insurance against a return of the secular-stagnation equilibrium. Inflation expectations never got unmoored from their 2% per year anchor—inflation expectations never became adaptive, let alone last-year-plus-one-percentage-point. Moreover, the Fed’s interest-rate increases had less of a depressing effect on the economy than I had feared, and whether by their skill or their luck we appear to have avoided recession and are nearly at the end of the glidepath to a soft macroeconomic landing.

Much kudos to the Fed.

And, were I Larry Summers right now, I would say:

My fears were greatly overblown.

The Fed team of Powell-Brainard-Williams and company are either incredibly skilled at this or incredibly lucky.

And was it Napoleon who said he would rather have a general who was lucky than one who is skilled?

Larry, however, does not appear to be hitting that sweet spot right now.

A big part of the problem is that the way his worries got out into the world was garbled.

Larry’s fear was not that inflation would settle at 7% per year, and that expectations would rise as people expected that to continue. Larry’s fear was that 7% per year inflation would drag the expectations anchor so that inflation expectations would settle at 4% per year—and that it would be the need to get them down to 2% per year that would bring on the recession. But the way the world heard the fear was that he was scared that inflation would settle at 7% per year, permanently.

Hence from his perspective he is being completely reasonable when he says:

One should always have been aware that a substantial part of the increase in inflation was transitory. So no one should have thought that most of the route from 7 per cent to 2 per cent needed to be achieved in ways that were correlated with increases in unemployment…

But in my inbox I find a bunch of smart and usually reasonable people—along with some who are not so reasonable and not so smart—being furious:

Paul Krugman: “Economists who were wrongly pessimistic about inflation—most prominently Larry Summers, although he isn’t alone—remain unwilling to accept the obvious. Instead, they argue that the Fed, which began raising interest rates sharply in 2022, deserves the credit for disinflation. The question is, how is that supposed to have worked? The original pessimist argument was… a lot of unemployment…. As best I can tell, the argument now is that by acting tough the Fed convinced people that inflation would come down, and that this was a self-fulfilling prophecy…”

Claudia Sahm: “Larry Summers’s interview is like getting gaslit by a blowtorch…. Encouragingly (and unexpectedly), Larry Summers… acknowledges what others like me have said for some time…”

David Dayen: “How Larry Summers’s Bad Predictions Hurt the Planet: The clean-energy transition is faltering because of unexpectedly high interest rates, which Summers’s demands to slow down the economy helped usher in…”

And there are many, many more.

My first reaction on reading these is that I do not understand how someone can argue about the Fed’s role in falling inflation without specifying a counterfactual.

The Federal Reserve sets short-term interest rates, buys and sells bonds, and uses its jawbone to provide forward guidance. Attributions of credit need to take the form of something like “The Fed decided to do X rather than Y and things have turned out well, as opposed to the Z that would have happened had the Fed done Y.” Without specifying the Y and the Z, no conversation has any chance of getting anywhere.

Behind Paul Krugman’s column there appear to be:

A Y in which the Federal Reserve did not raise interest rates at all (or raised them much less and much more slowly).

A Z in which the economy managed to continue on pretty much the same track as it actually did even though interest rates would have been much lower over the past two years.

Now if that is indeed Krugman’s Z this week, I find it highly implausible. The Federal Reserve has hit the economy on the head with a very large and heavy interest-rate brick that (a) greatly reduced the incentive to spend on long-lived assets and projects for the distant future and (b) raised the value of the dollar, thus giving Americans and others a big incentive to switch from buying American to buying foreign goods. Yes, the track of production has been much the same as I had forecast back when I had penciled in the Fed raising interest rates a lot less. There are two ways to reconcile how the economy has followed my production-path forecast with much higher interest rates:

Interest-rate increases no longer have significant effects on production.

I was greatly underestimating how strong the American economy’s demand-side was, and thus underestimating how fast production was likely to grow had the Federal Reserve been much more moderate raising interest rates.

And then there is the unknowable part of the question: Did the Federal Reserve’s interest-rate increases play a substantial role in keeping inflation expectations anchored at 2% per year? If the Federal Reserve had kept policy hands-off, would inflation expectations have shifted upward? I find it plausible that they would have. But I have no evidence.

On the other hand, nobody else has evidence either.

And now I see the wise and, as Claudia Sahm called him, “adorable” Olivier Blanchard responding to Paul on Twitter (but why on Twitter? Sharing a platform with Alex Jones in 2023 is not an especially good look):

If there is a “last mile” required to fully win the fight against US inflation, then indeed it will be a painful last mile. The wage Phillips curve is very flat: In layman terms, decreasing underlying inflation by even just 1% may require more unemployment for a while. The issue is whether there is indeed a last mile to run, or we have already run it, and things are just fine, as Paul Krugman tells us today in the NYT. It could be: It could be that the labor market is not as tight as it looks, and we do not need to increase unemployment. It could be that productivity growth is going to be higher, allowing for lower price inflation given wage inflation. We genuinely do not know. Better be careful in making victory or “need for more pain” statements…

I agree 100% with the “better be careful” sentiment.

But the statement that if there is a last mile:

indeed it will be a painful last mile. The wage Phillips curve is very flat… decreasing underlying inflation by even just 1% may require more unemployment for a while…

sneaks in the assumption that underlying inflation expectations are not certainly anchored at 2% per year, but instead might be higher by a percentage-point or two.

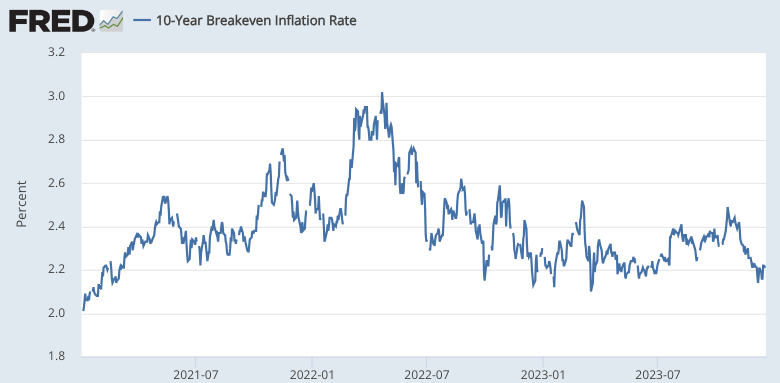

But how could inflation expectations have lost their anchor without it leaving traces in the bond market?:

There was reason in the tracks of the bond-market inflation-breakeven in early 2022 to fear that confidence in the Federal Reserve’s commitment to return inflation to 2% per year was slipping away—but the Fed than acted: it brought down the brick, the hammer, and market expectations moved back to their “the Fed has got this!” configuration.

And unless underlying inflation expectations are elevated, a flat wage Phillips Curve is not a reason to think that higher unemployment might be in any sense “necessary” for any not-unreasonable purpose.

Stepping back, I think one major thing going on is that Larry Summers tried to use the conceptual tool we call the Philips Curve, and it shattered in his hands—especially his (not unreasonable) belief that the Beveridge Curve had some slope. And so he expresses frustration:

it certainly hasn’t been a glorious period for the Phillips curve theory in any of its forms…. Inflation theory is in very substantial disarray, both because of the Phillips curve problems and because we don’t have a hugely convincing successor to monetarist-type theory…. Now that money pays interest, what the nominal quantity is, that is divided by a real quantity and sets the price level, is unclear…. Economics is embarrassingly short on clear, operational theories…

What I disagree with is his belief that sticking with a theory that is wrong is in some way preferable to retreating to a not-really-a-theory that might not be wrong:

The theory to which many economists are gravitating to is that the Phillips curve is basically flat, inflation is set by inflation expectations, and inflation expectations are set by the people who form inflation expectations. That’s a little bit like the theory that the planets go around the universe because of the orbital force. It’s kind of a naming theory rather than an actual theory…

References:

Aldritch, Philip: 2022. “Summers Says U.S. Needs 5% Jobless Rate for Five Years to Ease CPI.” Bloomberg, June 20, 2022. <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-06-20/summers-says-us-needs-5-jobless-rate-for-five-years-to-ease-cpi>.

Blanchard, Olivier: 2023. “If there is a ‘last mile’ required…”. Twitter December 19. <https://twitter.com/ojblanchard1/status/1737115914594857282>.

Dayen, David: 2023. “How Larry Summers’s Bad Predictions Hurt the Planet American ProspectNovember 20. <https://prospect.org/environment/2023-11-20-larry-summers-inflation-prediction-climate-change/>.

Krugman, Paul: 2023. “Beware Economists Who Won’t Admit They Were Wrong.” New York Times, December 19, 2023. <https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/18/opinion/inflation-economists.html>

Sahm, Claudia: 2023. “Larry Summers’s interview…”. Twitter December 17. <https://twitter.com/Claudia_Sahm/status/1737106446565990767>.

Summers, Lawrence: 2023. “We haven’t nailed the landing yet”. Financial Times December 14. <https://www.ft.com/content/59fff67e-b136-4435-89e1-2400b90f4b83>