TEACHING NOTE: E.P. Thompson & "The Making of the English Working Class"

I ran across a very nice appreciation of English Marxist historian E.P. Thompson by Madoc Cairns.

Cairns—I think correctly—sees Thompson as a man deeply influenced by the 1940s, when he thought much would be possible in the very bright future that would follow victory in World War II. period marked by immense suffering, hope, and disappointment. This decade profoundly shaped his perspectives and academic pursuits. The post-war disillusionment, the crushing of the Hungarian workers’ revolt in 1956, and the overshadowing threat of the hydrogen bomb are highlighted as pivotal influences on Thompson’s ideology. Cairns paints Thompson as a historian who sought to revive the neglected narratives of the working class, challenging the materialistic tendencies of contemporary socialist movements.

Cairns describes Thompson’s unique blend of not-really-Marxism-at-all as a blend of literary, moralistic, and secular Methodism. It certainly set Thompson apart from his contemporaries! This was especially tue in the context of the emerging radical movements of the 1960s.

Cairns’s appreciation piece not only sheds light on Thompson’s intellectual journey but also pleads for the enduring relevance of his work, particularly his The Making of the English Working Class in understanding the complexities of class consciousness in history.

Here is a quote from Cairns:

Madoc Cairns: The Making of EP Thompson <https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/history/2023/08/making-ep-thompson> ‘A colleague said of Edward that he remained “a man of the Forties” all his life, defined to the end by that decade’s sufferings and hopes and disappointments…. A decade on from the end of the war, and it seemed like the past was all EP Thompson had. The 1945 government “sank with all hands in full view of the electorate”; the idealism of the 1940s soured to apathy or curdled to cynicism, the peace Thompson fought for withering in the shadow of the hydrogen bomb. In 1956, a Hungarian workers’ revolt was crushed under the treads of Soviet tanks…. In Blake, and others like him, Thompson found a tradition he thought could “leaven” the soulless materialism of contemporary socialist movements–and a history of forgotten struggles that deserved to be illuminated…. The 1963 publication of his masterpiece: The Making of the English Working Class. “I am seeking to rescue,” Thompson wrote, in a sentence that would define his career, “the poor stockinger, the Luddite cropper, the ‘obsolete’ hand-loom weaver… from the enormous condescension of posterity”…. Thompson’s idiosyncratic Marxism–literary, moralistic, a kind of Methodism without God–was out of step with the “theatrical and irrational” left he saw emerging in the sixties…

And I thought: “I really will have to refer to this the next time I have students in a course reading E.P. Thompson’s ”The Making of the English Working Class”. But then I remembered:

I am 63;

European Economic History is no longer a thing we teach;

indeed, British Economic Histlry is really no longer a thing we teach.

Thus the chance that I will ever again have students to whom I assign Thompson is effectively zero.

Reflecting on this realization brings a sense of melancholy, as it underscores the changing landscape of academic priorities and the fading focus on specific areas of historical study. European and British Economic History, once staples in the academic curriculum, are now areas less traveled. Plus my time here on earth is finite. And these two have collided.

So I would like to at least try to pass the baton—cast bread upon the waters. Perhaps someone who will have students can pick up this baton, and run with it…

So here goes:

E.P. Thompson’s is an unusual kind of social and economic and cultural history:

It is not the main force, the typical experience, of humanity or a broad segment thereof. Thompson’s work diverges from traditional historical narratives that often focus on the predominant forces or general experiences of large segments of society. Instead, he delves into the nuanced and often overlooked aspects of the working class, highlighting their unique experiences, struggles, and contributions to history. This approach sheds light on the complexities of social and economic dynamics, revealing the intricate interplay between various societal forces. Thompson’s emphasis on the working class as active agents in their own history challenges conventional historical perspectives and provides a more inclusive understanding of the past. His work serves as a reminder of the importance of considering diverse experiences and viewpoints in the study of history.

It is not how a typical human being swimming in the economic and social tides made sense of it all. Thompson’s narrative is distinct in its focus on how the working class, rather than the typical individual, grappled with and responded to the tumultuous economic and social changes of their time. He explores the collective consciousness and actions of the working class, offering insights into their shared experiences, struggles, and aspirations. This perspective shifts the historical lens from the individual to the collective, highlighting the importance of community and solidarity in shaping historical events. Thompson’s approach provides a deeper understanding of the social fabric and the collective forces that drive historical change.

It is not how élites, parasitic and predatory, spun their own webs of culture and thought and used them in large part for the “fraud” part of their force-and-fraud domination-and-exploitation machine. Thompson’s analysis contrasts with narratives that often center on the actions and perspectives of the elite. He avoids portraying history as merely the outcome of elite machinations, instead emphasizing the role of the working class in resisting and challenging these forces. By focusing on the working class’s response to exploitation and domination, Thompson sheds light on the resistance and agency of those often marginalized in historical accounts. This approach underscores the dynamic interplay between different social classes and the impact of this interaction on the course of history.

It is not the roots of ideas that then became the motivators of powerful social forces that shaped and shape history. In Thompson’s view, the genesis of ideas that drive social forces is not the central theme. Rather, he is more concerned with how these ideas are adopted, adapted, and utilized by the working class in their struggle for recognition and rights. His focus is on the lived experiences and collective actions of the working class, and how these, in turn, influence and reshape the ideas and forces that drive history. This perspective highlights the reciprocal relationship between ideas and social movements, emphasizing the role of the working class in not just being shaped by, but also in shaping, the course of history.

So what is it? It is… itself. As Cairns put it: “Methodism without God… out of step with the ‘theatrical and irrational’ left… [of] the sixties”, and focused on rescuing “the poor stockinger, the Luddite cropper, the ‘obsolete’ hand-loom weaver… from the enormous condescension of posterity”.

Here are three things from Thompson to focus on:

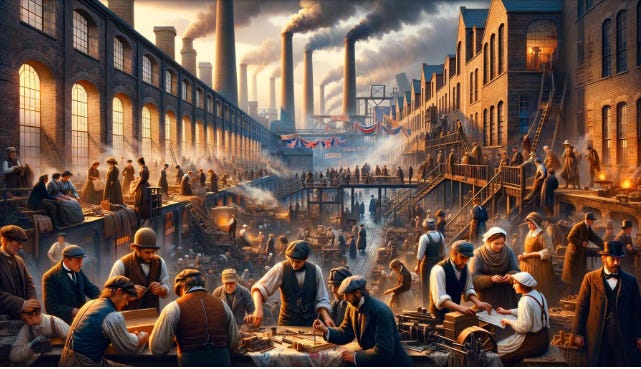

First, here is Thompson’s vision of English working-class identity and consciousness as made by people—people picking up Methodist and other intellectual tools and using them to try to create platforms so that they could preserve and also change the world. How? They sought to preserve their existing sources of social power and also, in the new economic world coming to be, extend to themselves Polanyian rights—to land, labor, and finance; to community, to respect and reward, and to economic stability and insurance—against the mercantile-industrial market forces of Schumpeterian creative-destruction and against the rewelding of the upper-class élite force-and-fraud domination-and-exploitation machine into the fabric of property and formal equality:

Diversity of experiences has led some writers to question both the notions of an “industrial revolution” and of a “working class.” The first discussion need not detain us here? The term is serviceable enough in its usual connotations. For the second, many writers prefer the term working classes, which emphasises the great disparity in status, acquisitions, skills, conditions, within the portmanteau phrase. And in this they echo the complaints of Francis Place:

“If the character and conduct of the working-people are to be taken from reviews, magazines, pamphlets, newspapers, reports of the two Houses of Parliament and the Factory Commissioners, we shall find them all jumbled together as the “lower orders,” the most skilled and the most prudent workman, with the most ignorant and imprudent labourers and paupers, though the difference is great indeed, and indeed in many cases will scarce admit of comparison…”

Place is, of course, right: the Sunderland sailor, the Irish navvy, the Jewish costermonger, the inmate of an East Anglian village workhouse, the compositor on The Times–all might be seen by their “betters” as belonging to the “lower classes” while they themselves might scarcely understand each others’ dialect.

Nevertheless, when every caution has been made, the outstanding fact of the period between 1790 and 1830 is the formation of “the working class.” This is revealed, first, in the growth of class-consciousness: the consciousness of an identity of interests as between all these diverse groups of working people and as against the interests of other classes. And, second, in the growth of corresponding forms of political and industrial organisation. By 1832 there were strongly-based and self-conscious working-class institutions–trade unions, friendly societies, educational and religious movements, political organisations, periodicals–working-class intellectual traditions, working-class community-patterns, and a working-class structure of feeling.

The making of the working class is a fact of political and cultural, as much as of economic, history. It was not the spontaneous generation of the factory-system. Nor should we think of an external force–the “industrial revolution”–working upon some nondescript undifferentiated raw material of humanity, and turning it out at the other end as a “fresh race of beings.” The changing productive relations and working conditions of the Industrial Revolution were imposed, not upon raw material, but upon the free-born Englishman–and the free-born Englishman as Paine had left him or as the Methodists had moulded him. The factory hand or stockinger was also the inheritor of Bunyan, of remembered village rights, of notions of equality before the law, of craft traditions. He was the object of massive religious indoctrination and the creator of new political traditions. The working class made itself as much as it was made… (p. 212)

For Thompson, the formation of the working class was a complex and multifaceted and above all cultural process. He wants to recognize the diversity within the working class. But he also wants to claim—or perhaps simply will into being by his pen—the growth of a collective consciousness that transcended individual group differences. The working classes actively participated in their own making, yes—political and industrial organization, intellectual traditions, and community patterns. But did they make a single thing? He thinks so, in large part because of their drawing on the same religious and ideological background—Methodism and Thomas Paine. But is he right?

Second, here is Thompson trying to elucidate why, in his mind, the pre–1830 mental-cultural story he focuses on matters. I do not think he succeeds—rather, it failed, because, while “both the Romantics and the Radical craftsmen opposed the annunciation of Acquisitive Man… [it was] the failure of the two traditions to come to a point of junction… [that] makes us among the losers”:

This collective [working-class] self-consciousness was indeed the great spiritual gain of the Industrial Revolution, against which the disruption of an older and in many ways more humanly comprehensible way of life must be set. It was perhaps a unique formation, this British working class of 1832…. From Tudor times onwards this artisan culture had grown more complex with each phase of technical and social change…. Enriched by the experiences of the seventeenth century, carrying through the eighteenth century the intellectual and libertarian traditions which we have described, forming their own traditions of mutuality in the friendly society and trades club, these men did not pass, in one generation, from the peasantry to the new industrial town. They suffered the experience of the Industrial Revolution as articulate, free-born Englishmen. Those who were sent to gaol might know the Bible better than those on the Bench, and those who were transported to Van Diemen’s Land might ask their relatives to send Cobbett’s Register after them.

This was, perhaps, the most distinguished popular culture England has known. It contained the massive diversity of skills, of the workers in metal, wood, textiles and ceramics, without whose inherited ‘mysteries’ and superb ingenuity with primitive tools the inventions of the Industrial Revolution could scarcely have got further than the drawing-board. From this culture of the craftsman and the self-taught there came scores of inventors, organizers, journalists and political theorists of impressive quality. It is easy enough to say that this culture was backward-looking or conservative.

True enough, one direction of the great agitations of the artisans and outworkers, continued over fifty years, was to resist being turned into a proletariat. When they knew that this cause was lost, yet they reached out again, in the Thirties and Forties, and sought to achieve new and only imagined forms of social control. During all this time they were, as a class, repressed and segregated in their own communities. But what the counter-revolution sought to repress grew only more determined in the quasi-legal institutions of the underground.

Whenever the pressure of the rulers relaxed, men came from the petty workshops or the weavers’ hamlets and asserted new claims. They were told that they had no rights, but they knew that they were born free. The Yeomanry rode down their meeting, and the right of public meeting was gained. The pamphleteers were gaoled, and from the gaols they edited pamphlets, The trade unionists were imprisoned, and they were attended to prison by processions with bands and union banners.

Segregated in this way, their institutions acquired a peculiar toughness and resilience. Class also acquired a peculiar resonance in English life: everything, from their schools to their shops, their chapels to their amusements, was turned into a battleground of class. The marks of this remain, but by the outsider they are not always understood. If we have in our social life little of the tradition of égalité, yet the class-consciousness of the working man has little in it of deference. ‘Orphans we are, and bastards of society,’ wrote James Morrison in 1834. The tone is not one of resignation but of pride.

Again and again in these years working men expressed it thus: ‘they wish to make us tools’, or ‘implements’, or ‘machines’. A witness before the parliamentary committee enquiring into the hand-loom weavers (1835) was asked to state the view of his fellows on the Reform Bill:

“Q. Are the working classes better satisfied with the institutions of the country since the change has taken place?

“A. I do not think they are. They viewed the Reform Bill as a measure calculated to join the middle and upper classes to Government, and leave them in the hands of Government as a sort of machine to work according to the pleasure of Government…”

Such men met Utilitarianism in their daily lives, and they sought to throw it back, not blindly, but with intelligence and moral passion. They fought, not the machine, but the exploitive and oppressive relationships intrinsic to industrial capitalism. In these same years, the great Romantic criticism of Utilitarianism was running its parallel but altogether separate course. After William Blake, no mind was at home in both cultures, nor had the genius to interpret the two traditions to each other. It was a muddled Mr Owen who offered to disclose the ‘new moral world’, while Wordsworth and Coleridge had withdrawn behind their own ramparts of disenchantment. Hence these years appear at times to display, not a revolutionary challenge, but a resistance movement, in which both the Romantics and the Radical craftsmen opposed the annunciation of Acquisitive Man. In the failure of the two traditions to come to a point of junction, something was lost. How much we cannot be sure, for we are among the losers.

Yet the working people should not be seen only as the lost myriads of eternity. They had also nourished, for fifty years, and with incomparable fortitude, the Liberty Tree. We may thank them for these years of heroic culture… (pp. 913–5)

I think he fails: it did not matter much.

And, however insightful Thompson’s individual observations, he overlooks the more impactful drivers of the evolution of British liberty and democracy. The real catalysts were the gradual extension of the franchise to the middle class, followed by the knock-on effects of the profound societal shocks of the suffragette movement and World War I. These events collectively reshaped the political landscape and brought about British democracy. The middle-class franchise extension, in particular, marked a significant shift in the balance of power, allowing a broader segment of society to participate in the political process. Working-class pleas for the liberties of Englishmen cut no ice as long as the middle classes bought into the hierarchical system of the Great Chain of Being. It was only after that fell—after politicians rallied middle-class support. It was only when David Lloyd George could say and win votes by saying: ““A fully equipped duke costs as much to keep up as two Dreadnoughts—and they are just as great a terror—and they last longer…” that Britain could become a democracy.

Third, from 1973, a plea in his “Open Letter to Leszek Kolakowski” to Polish exile Leszek Kolakowski that Kalakowski not cast anti-Stalinist western Marxists—like E.P. Thompson—into the outer darkness:

Western intellectuals were not converted to Stalinism (or, in the first case, “to Hitlerism or Stalinism” – and why “Hitlerism” rather than the more analytic terms “Nazism” or “Fascism”?) only because they were either (1) conscious converts to barbarism, or (2) attracted by Marxist universalism, or (3) – and finally – tempted by the vision of Splendid Asiatics destroying European decadence. There were many, and more potent, motivations, both intellectual and in actual experience. I am unclear as to the distinction between two of the motivations you have selected: is it that in (1) the love is a love of barbarism tout court whereas in (3) we have a finer precision: the barbarism must be “Asiatic”?

The discrimination, nice as it is, need not detain us, since while you might find, here or there, individual men, or statements by other men taken out of wider contexts, which supported your argument that such motivations were present, I defy you to show that these motivations were sufficiently widely distributed to be generalized in this way, or could be given anything like the priority among other motivations which you assert. I hold the unfashionable view – a view which is today most unfashionable of all among the non- or anti-Communist Left – that, in terms of the choices presented to them, the Communists of the 1930s and 1940s were not altogether wrong, intellectually or politically; certainly, that they were not wrong all of the time.

I know that the Western Communist intellectuals with whom I associated did not sustain themselves with visions of splendid Asiatics marching upon the West: their visions were of Panzers or of Sherman tanks rolling into the East, breathing racial purity or the freedom of capital down the barrels of their guns.

This is not a page of apologetics. I am simply asking for analysis and not caricature. One of the first casualties of Stalinist “realist” thought, I know, was Poland. And you, a Pole, cannot lightly forgive such an error. In saying that your thought comes from that tragic context – and I say it with humility – I am also saying that you cannot but think about this in a Polish idiom.

The point which I was offering to illustrate is that you have been passing from irony to caricature: or to mere abuse. Irony may be directed both against a friend and an antagonist. If used with effect, it is a small, accurate, fine-tempered weapon. It may wound, but it can wound only the particular point – the idea, the characteristic – at which it is directed. It is no blunt, belligerent instrument, as is abuse. Irony must succeed in striking exactly where it is aimed. If the aim misses, then it is not the victim but the ironist who is caught off-balance. And if the aim is good, the victim’s ideas are not thereby “exploded”, utterly exposed: they are questioned or corrected at one particular point. The wound may smart for a moment, but it will heal. Life evidences daily that friendship and indeed marriage can survive the mutual exchange of ironies.

They will not survive abuse nor repeated caricature. For caricature – when it is applied to thought or social movements – signals exactly that dialogue can no longer be sustained… https://www.marxists.org/archive/thompson-ep/1973/kolakowski.htm

Again, this failed. From Kolakowski’s perspective, for Leftists to focus on the idea of “Sherman tanks rolling into the East, breathing… the freedom of capital down the barrels of their guns…” while Poland was being excruciatingly flayed is truly unforgivable

It represents a significant misalignment of priorities and a lack of empathy for the suffering endured by those in the Soviet sphere, particularly in Poland. This myopic view not only minimizes the tragedy experienced by these nations but also, in Kolakowski’s eyes, demands a response that transcends mere irony. Such a skewed perspective warrants a stronger reaction, one of caricature, contempt, and outright dismissal. In this light, Kolakowski’s harsh critique of Western Leftist thought is not just a pedantic exercise in intellectual debate but a necessary corrective to a dangerously misguided and simplistic worldview that fails to grasp the complex and painful realities of Eastern Europe during the Cold War.

In my view—his pleas for nuclear disarmament aside—by 1973 E. P. Thompson had no purchase either on political action in or on the intellectual understanding of the societies we were moving into. By my count, 1938-1973 saw the hitherto greatest forward advance of human society in economic prosperity and political organization—under the banner of what became the post-WWII social democracy and New Deal Order of the Thirty Glorious Years. E.P Thompson’s reaction was not to reëvaluate his intellectual and political commitments of the 1940s, but rather to double-down in a manner leading me, at least, to profoundly question his judgment. In his “Open Letter” he writes that:

No matter how hideous the alternative may seem, no word of mine will wittingly be added to the comforts of that old bitch gone in the teeth, consumer capitalism. I know that bitch well in her very original nature; she has engendered world-wide wars, aggressive and racial imperialisms, and she is co-partner in the unhappy history of socialist degeneration…. “My” progenitors, and some of my contemporaries, have sown their lives into furrows… like a botanical prophylactic, to restrain the virulence of capitalist logic. And to the degree that they have succeeded, the apologists of capitalism appear with newly-soaped faces, and offer their beast as a beast of changed nature. But I know that that beast is not changed…

That the advances were, in a sense, profoundly false, because they came about under the wrong system.

In this, I think E.P. Thompson echoes Orwell, who wrote in his Road to Wigan Pier that the real problem was:

In a decade of unparalleled depression, the consumption of all cheap luxuries has increased. The two things that have probably made the greatest difference of all are the movies and the mass-production of cheap smart clothes since the war. The youth who leaves school at fourteen and gets a blind-alley job is out of work at twenty, probably for life; but for two pounds ten on the hire-purchase system he can buy himself a suit which, for a little while and at a little distance, looks as though it had been tailored in Savile Row. The girl can look like a fashion plate at an even lower price.

You may have three halfpence in your pocket and not a prospect in the world, and only the corner of a leaky bedroom to go home to; but in your new clothes you can stand on the street corner, indulging in a private daydream of yourself as Clark Gable or Greta Garbo, which compensates you for a great deal. And even at home there is generally a cup of tea going—a “ nice cup of tea “— and Father, who has been out of work since 1929, is temporarily happy because he has a sure tip for the Cesarewitch…

Fake prosperity, sold under false pretences, for the working class really does deserve real bespoke tailoring and real silk stockings—but has been persuaded that off-the-rack and nylons are good enough for them.

Food for thought.

Last, Madoc Cairns has a nice piece about Kolakowski too:

Really-Existing Socialism: Madoc Cairns: Settling scores with God: Leszek Kolakowski at the End of History <https://www.newstatesman.com/ideas/2023/06/settling-scores-god-leszek-kolakowski-end-of-history-poland>: ‘How the Marxist-turned-Catholic-conservative remains the pre-eminent thinker for our age of tragedy…. Kolakowski… arguing, in essays such as “The Concept of the Left” that socialism is a moral ideal… emerged as a leader of the reform movements that were rising across the eastern bloc…. In 1988 Kolakowski published Metaphysical Horror, the book he considered his masterpiece. After the Enlightenment no meaning is self-created, Kolakowski wrote; all values are imputed values. But imputed by what? This radical uncertainty—this “metaphysical horror”—threatened the eclipse of meaning entirely. Kolakowski, like Pascal, saw an abyss on the edge of his sight. But where Pascal chose transcendent faith, Kolakowski chose something more ambivalent…. What did he see when he looked forwards? Nothing good. The Enlightenment was a “catastrophe”, he wrote, but an irreversible one. Our last hope of avoiding “civilisational suicide”, one late essay said, is to “run very fast to stay in the same place”. Later, it seemed, even that hope was lost. In one of his final interviews Kolakowski reiterated Metaphysical Horror’s argument: our need for meaning persists, but our ability to comprehend it slips away…

This passage underscores Kolakowski’s evolution from a Marxist thinker to a near-Catholic conservative, starting from his role in Eastern European reform movements and moving on to philosophical explorations that transcend mere political ideology, as he dismisses them as inadequate and finds refuge in near-theology. Kolakowski’s dismissal of the Enlightenment as a ‘catastrophe’ and his contemplation of ‘civilizational suicide’ and the fading comprehension of meaning in a rapidly changing world echoes the profound uncertainty and existential dread of contemporary society.

Does this reflect the broader anxieties of our age, where rapid social and technological changes challenge our traditional notions of meaning and purpose? Perhaps.

Kolakowski, however, is wise enough to conclude that the Enlightenment cannot be undone—and should not be undone, as pre-Enlightenment certainties will always be dissolved by new waves of technological, economic, and sociological change as long as our collective powers to control nature and organize ourselves keep advancing by leaps and bounds.

In this, Kolakowski strikes me as far wiser than Alasdair MacIntyre, another towering figure in 20th-century philosophy whose intellectual journey bears striking parallels. Both thinkers embarked on a path that saw them veering away from their early Marxist commitments, leading to a profound reevaluation of moral and political philosophy. MacIntyre, much like Kolakowski, grappled with the challenges posed by modernity to traditional moral frameworks. His seminal work, After Virtue, reflects a quest similar to Kolakowski’s, where he scrutinizes the foundations of ethical theory in the post-Enlightenment era, questioning the fragmentation and incoherence of contemporary moral discourse.

Both philosophers, in their unique ways, lamented the loss of a unified moral community, which in earlier societies provided a coherent backdrop against which moral life was understood and lived. This shared intellectual trajectory underscores a broader philosophical inquiry into the nature of morality, ethics, and society in a post-traditional world. Kolakowski and MacIntyre, through their respective works, offer critical insights into the dilemmas facing modern societies, highlighting the tensions between individual agency, communal values, and the legacy of Enlightenment thought. Their journey converge on the crucial question of how to navigate a world where traditional moral anchors have been eroded, leaving a void that challenges both individual and collective notions of the good life.

The major difference is that Kolakowski understands the dilemmas. Macintyre, by contrast, persuades himself into the ludicrous posture of pretending that Aquinas said everything that needs to be said long ago.

References:

Cairns, Madoc. 2023. “Making of EP Thompson.” New Statesman, August 15. <https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/history/2023/08/making-ep-thompson>.

Cairns, Madoc. 2023. “Settling Scores with God: Leszek Kolakowski at the End of History.” New Statesman, June 21. <https://www.newstatesman.com/ideas/2023/06/settling-scores-god-leszek-kolakowski-end-of-history-poland>.

MacIntyre, Alasdair C. 1981. After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press. <https://www.archive.org/details/aftervirtuestudy0000maci>

Orwell, George. 1937. The Road to Wigan Pier. London: Victor Gollancz Ltd.<https://www.archive.org/details/TheRoadToWiganPier>.

Thompson, E. P. 1964. The Making of the English Working Class. New York: Pantheon Books. <https://archive.org/details/makingofenglishw0000epth>.

Thompson, E.P. 1973. “Open Letter to Leszek Kolakowski.<https://www.marxists.org/archive/thompson-ep/1973/open-letter.htm>.