HOISTED FROM ÞE ARCHIVES: Six Episodes of U.S. Inflation Above 5%/Year in þe 1900s

I think that the answer to the big question is clear: 1947 and 1951 look like much better models of what is going on in our current inflation than do 1974 and 1979. Those whose only model of the inflation process was an accelerationist Phillips curve in which this year’s current headline inflation was the inflation rate expected for next year got it very wrong indeed.

To quote myself: Truth be told, there is no economic theory. There is only history, and its events, and analogies we make based on judgments concerning complicated emergent processes we do not understand very well that come out of the millions of interactions that are the economy.

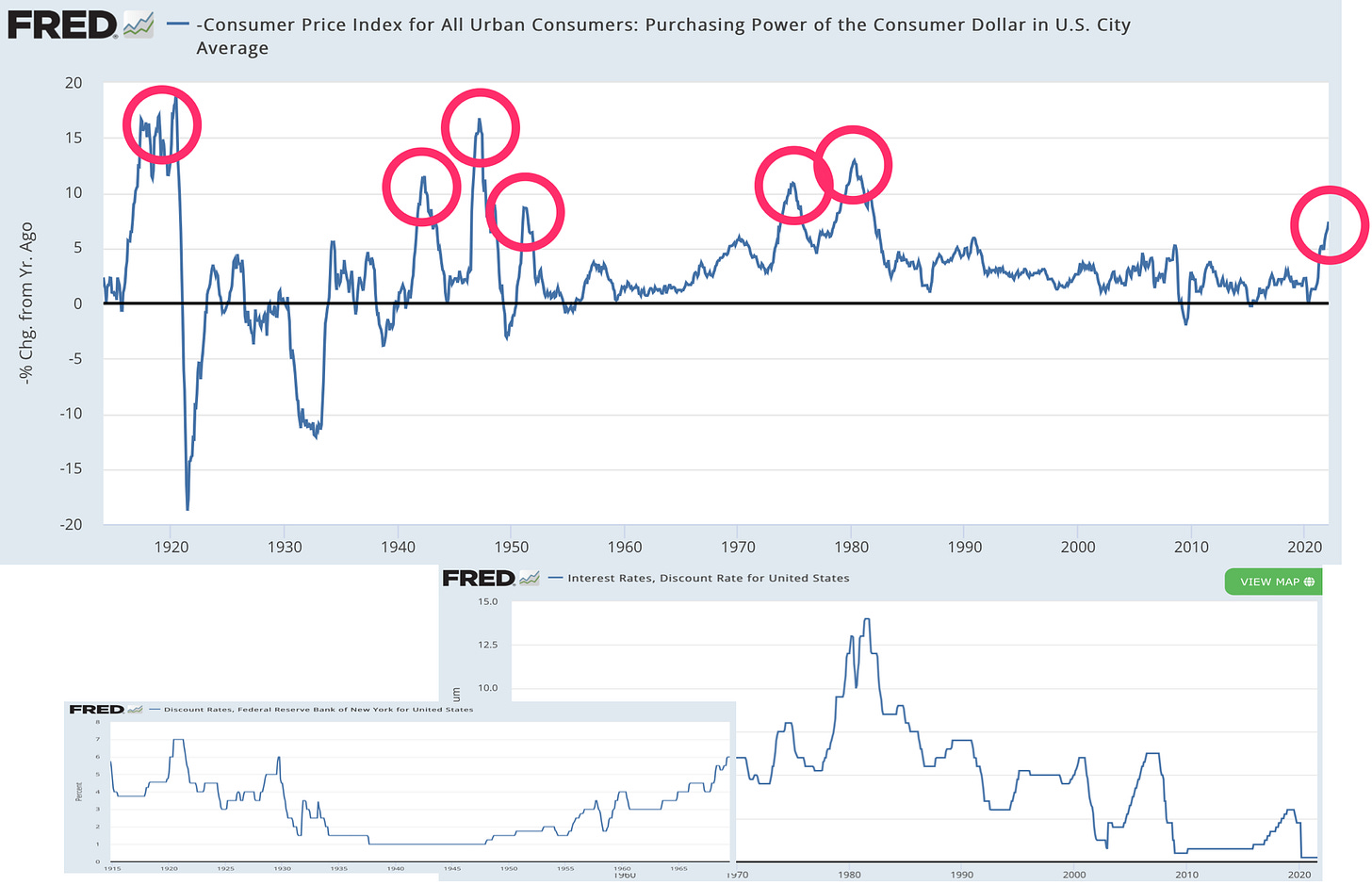

The top graph is the CPI inflation rate; the bottom graphs are overlapping graphs of the Federal Reserve’s discount rate—the rate at which it lends to banks on reasonable collateral.

Counting 1974 and 1979 as two episodes, there were six times in the twentieth century during which the annual inflation rate got above 5%. One was the World War II inflation—cut off by price controls. Then came the post-WWII structural-rebalancing-and-pent up demand inflation, and then the Korean War structural-rebalancing inflation as the U.S. government wheeled its economy to fight the Cold War. During both the Fed sat by—it was then still focused on keeping the prices of Treasury bonds high. The inflations soon passed away.

Before those came the World War I episode. That episode of inflation was cut off by an increase in the discount rate from 3.75%/year to 7%/year, which not only ended the inflation but enforced deflation: a 20% decline in the price level from its peak. (This decline, I should ask, made the task of restoring the gold standard at anything like pre-World War I nominal parities much more difficult, hence much more pointless.) Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz judged that the rise was “not only too late but also too much” <https://archive.org/details/monetaryhistoryo0000frie/page/230/>: the Fed should have moved earlier to prevent excessive bank discounts from inappropriately boosting high-powered money, and at the moment the Fed did move the structure of credit was sufficiently based on a continuation of Fed policy that the Fed’s move generated “one of the most rapid declines [in economic activity] on record”.

If the Federal Reserve had not moved to raise discount rates after World War I, what would have happened? Friedman and Schwartz’s judgment is that an earlier increase of, say, 125 basis points to remove the incentive for banks to engage in excessive discounts would have brought the excessive growth of the high-powered money stock to an end, and stopped the inflation.

Then came the 1970s: The Fed raised interest rates after the Yom Kippur War oil shock to control inflation; then, after inflation peaked, it lowered them to try to restore full employment; then came the year when, as the late Charlie Schultze said, “our forecasts of nominal income growth were dead on, but inflation came in 2%-points high and real growth 2%-points low”; and then came the Volcker disinflation, reversed in September 1982 when they realized that they had bankrupted Mexico, and not resumed as the Fed decided to declare a fall in inflation to the 4-5%/year range as complete victory. That 4-5% target lasted for a decade, followed by the opportunistic disinflation down to and Alan Greenspan’s declaration of the 2%/year inflation target—a declaration that it is very hard today to argue was appropriate, given the extraordinary amount of time global north economies have spent with interest rates at their zero lower bound since.

What does macroeconomic theory tell us that the Federal Reserve should do now, in the spring of 2022?

Olivier Blanchard writes:

In early 1975, core inflation was running at 12 percent and the real policy rate was equal to about −6 percent, a gap of about 17 percent. Today, core inflation is running at 6 percent and the real policy rate is equal to −6 percent, a gap of 12 percent—smaller than in 1975, but still strikingly large…. It then took 8 years, from 1975 to 1983, to reduce inflation to 4 percent, with an increase in the real rate from bottom to peak of close to 1,300 basis points, and a peak increase in the unemployment rate of 600 basis points from the early 1970s. Today is obviously different in many ways…. [But even so,] it reasonable to think that a 200-basis-point increase in the policy rate, so only 1/6 of the rate increase from 1975 to 1981, will do the job this time when the gap between core inflation and the policy rate is 2/3 of what it was in 1975? And that unemployment will barely budge? I wish I could believe it… <https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/why-i-worry-about-inflation-interest-rates-and-unemployment>

The suggestion seems to be that we have today 2/3 of the problem we had in 1975, and so the solution would be to do 2/3 as much—to raise interest rates by 800 basis points, 8% points—but then to apply some haircut to that 800 basis-point interest-rate rise because “today is obviously different in many ways”.

But why does he pick 1975-1983, rather than 1951 or 1948 or 1920? Does economic theory tell him to do so?

Truth be told, there is no economic theory. There is only history, and its events, and analogies we make based on judgments concerning complicated emergent processes we do not understand very well that come out of the millions of interactions that are the economy. Sometimes, it is true, we distill and crystallize the history into something we call theory where little squiggles that look like ɣ, δ, β, σ, and so on; we then mainline the crystallized product. After mainlining it we can think we know something. But after mainlining crystal meth we experience increased energy, elevated mood, extraordinary confidence, racing thoughts, muscle twitches, and rapid breathing, among other things.

Move cautiously. Be data-dependent. Wait for it to become clearer which, if any, historical analogies are relevant to our situation. And always, always, always remember that in an economy that is near and that we have a good reason to fear will long remain in danger of hitting the zero lower bound on nominal interest rates, premature and excessively aggressive moves that raise interest rates cannot easily be corrected.