REVIEW: Martin Turkis on "Slouching Towards Utopia"

J. Bradford DeLong. Slouching Towards Utopia. New York, NY: Basic Books, 2022. ISBN 9780465019595. Hardcover $35 <http://bit.ly/3pP3Krk>

>

Martin Turkis:

J. Bradford DeLong is an economist at UC Berkeley who has exercised significant influence over the course of his career. In the early 1990s he co-wrote, with Lawrence Summers, two papers that provided the theoretical game plan for the Clinton Administration’s approach to neoclassical financial deregulation during Summers’s tenure as Secretary of 35 the Treasury. DeLong himself worked as a Treasury official during this same period. His own theoretical legacy from the Clinton era can be fairly described as left neoliberal. He was, in his own terms, a “Rubin Democrat” (a reference to the market- and finance-friendly Robert Rubin), espousing “largely neoliberal, market-oriented…tuning aimed at social democratic ends” while in political terms advocating “taking a step in the direction of appeasing conservative priorities” (quoted in Beauchamp 2019). He has since modified his position with regard to the company that market-oriented thinkers with social democratic aims ought to keep, claiming that Democrat party elites should embrace and partner with the resurgent social democratic left that emerged alongside the candidacy of Bernie Sanders.

DeLong himself has summed up the central arguments delivered in his long book:

Since 1870, we humans have done amazingly, astonishingly, uniquely, and unprecedentedly well at baking a sufficiently large economic pie.

But the problems of slicing and tasting the pie—of equitably distributing it, and then using our technological powers to live lives wisely and well—continue to flummox us.

The big reason we have been unable to build social institutions for equitably slicing and then properly tasting our now more-than sufficiently-large economic pie is the sheer pace of economic transformation.

Since 1870 humanity’s technological competence has doubled every generation. Hence Schumpeterian creative destruction has taken hold.

Our immensely increasing wealth has come at the price of the repeated destruction of industries, occupations, livelihoods, and communities.

And we have been frantically trying to rewrite the sociological code running on top of our rapidly changing forces-of-production hardware.

The attempts to cobble together a sortarunning sociological software code have been a scorched-earth war between two factions.

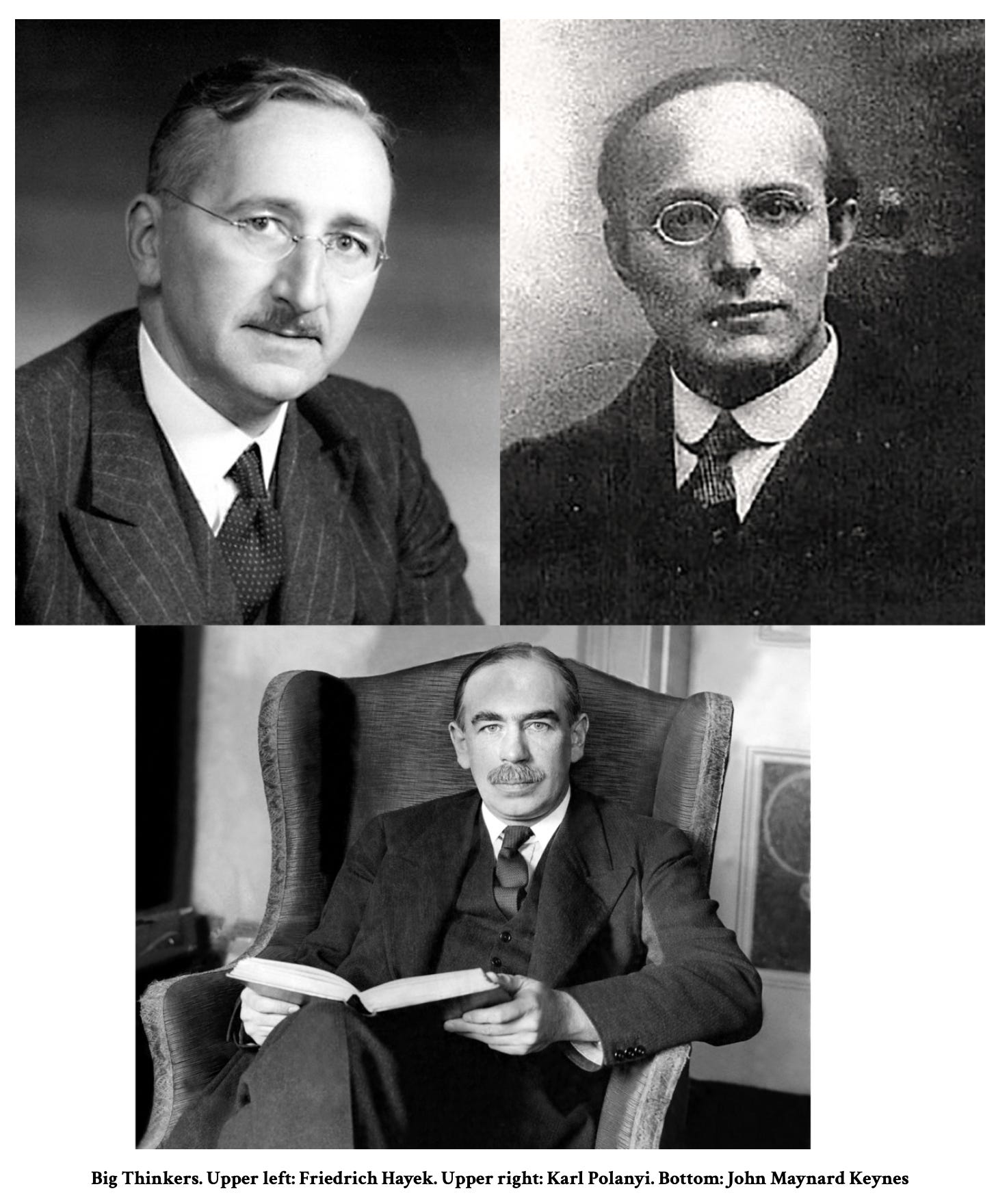

Faction 1: followers of Friedrich von Hayek, who say “the market giveth, the market taketh away: blessed be the name of the market.”

Faction 2: followers of Karl Polanyi, who say “the market was made for man; not man for the market.”

Let the market start destroying “society,” and society will react by trying to destroy the market order.

Thus the task of governance and politics is to try to manage and perhaps one day supersede this dilemma.

These arguments are communicated in the context of a grand narrative that traces the contours of what DeLong calls the “long twentieth century” (1870–2010), a coinage he presents in opposition to British-Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm’s “short twentieth century” (1914–1991). The long twentieth century, in DeLong’s analysis, is marked by the “triple emergence of globalization, the industrial research lab, and the modern corporation” (1), a trio that allowed humanity at large to escape (to a significant extent) the sort of subsistence existence that had dominated our lot since the advent of agriculture. For DeLong, 2010, in the wake of the Great Recession, marks the end of the era in which economic growth allowed for a continuation of this trend whereby more and more of the world’s population escaped lives of mere subsistence.

He recognizes European-style social democracy and, to a lesser extent, the New Deal social democracy of the United States as the highest achievement of this long, high-growth century. He creatively describes this social democratic achievement as the “shotgun marriage of Hayek and [Karl] Polanyi blessed by Keynes” (DeLong 2022, 6), by which he means to emphasize the incorporation of the decentralized power of market mechanisms into a societal structure that honors what he calls “Polanyian rights”—rights that would guarantee that “those who do not own valuable property should have the social power to be listened to, and that societies should take their needs and desires into account” (ibid., 5). Such a rapprochement between Hayek and Polanyi would be impossible, in DeLong’s view, without the judicious application of Keynesian insight. This sort of arrangement, if on a gradual track toward wider and wider inclusion, is the incremental, non-revolutionary utopia that, on DeLong’s account, we slouched towards through most of the long twentieth century.

The bulk of his narrative is concerned with the ways the triple emergence referenced above was harnessed and developed (or not) around the world in the context of ongoing ideological debates, political shifts, and revolutions hinging on the role of markets in society—that is to say, to the extent that Hayek’s views or Polanyi’s held sway. DeLong keeps this debate alive throughout by employing his two framing figures as a tragic chorus that provides commentary on the evolution of political economy. Together we visit Europe, the US, Meiji Japan, China, Africa, India, etc. The villains of the tale are totalitarians, whether fascist, Nazi (if we accept the distinction), or Bolshevik. Given the defeat in WWII of the reactionary totalitarians, the “reallyexisting-socialism” of the Leninist-Stalinist USSR serves as the longest-running foil to the social freedom achieved by embedding markets within social democracy.

The breadth of DeLong’s historical knowledge is impressive, and his prose is readable and lively. While Karl Polanyi’s thought is a central focus throughout the book, DeLong also mentions Michael Polanyi in a passage in which he glosses a number of figures he would have included in his history had time and space allowed. He singles out the younger Polanyi as important due to his theorization of society’s need to transcend both the mercenary nature of the free market and attempts at comprehensive central planning by means of “decentralized fiduciary institutions focused on advancing knowledge about theory and practice…in which people follow rules that have been half-constructed and that half emerged to advance not just the private interests and liberties of the participants but the broader public interest and public liberties as well” (ibid., 168).

He intersperses his text where appropriate with self-reflective commentary on his own participation (as a relatively influential economist and high-level apparatchik under Clinton) in the neoliberal turn. This is very much to his credit, since it is most apparent when he regards his own involvement in the neoliberal turn, the “hubris” of which “truly brought forth nemesis” (ibid., 463). He is also open and clear that presenting a grand narrative, as he does, will necessitate overlooking certain details and nuances in the wide-ranging subject matter he treats. Fair enough. Nonetheless I will mention three themes that I would have liked to see figure more prominently:

DeLong might have considered our retrospective recognition that environmental destruction is endemic to industrialization. This is a pretty fair candidate to derail any possibility of long-term progress, slouching or otherwise. The impending consequences of industrial environmental degradation are addressed in the final chapter or so, but almost as an afterthought. In contrast to this, DeLong works commentary and analysis throughout the body of his text that recognize other problems that were festering throughout the long twentieth century but perhaps went unrecognized by those in control of societies until later. The exclusion of women and marginalized racial groups from full social participation, for instance, is addressed in parenthetical commentary interspersed throughout the book, whereas the future environmental costs of industrialized globalization are not handled with such consistency.

DeLong might have considered the ways in which the really-existing-socialism of the Soviet sphere—as a live, counter-hegemonic alternative to Western liberalism—may have given progressive reformers like FDR, civil rights activists, or those who engineered European social democracy the leverage necessary to overcome forces of reaction that opposed such [Karl] Polanyian shifts. Would the social democratic achievements of the New Deal have happened, for example, if big business, etc. didn’t feel that an American rerun of the Bolshevik Revolution were a real threat in the aftermath of the Great Depression? These questions, open to debate, seem relevant to his narrative but don’t make much of an appearance.

I concur with DeLong’s approval of social democracy as the highest political economic achievement of the long twentieth century. I would like to have heard more from him in the book about the specifics of how the successful social democracies function(ed) and the distinctions, if such there be in his view, between social democracy and democratic socialism.

Overall, Slouching Towards Utopia is a fascinating, readable, and worthwhile book that comes highly recommended, regardless of one’s ideological commitments.

I reply: Thx much for this. A few comments:

a. Michael Polanyi is smarter and saw further than Friedrich von Hayek. I toyed with making the main axis of tension an inter-family dispute, but in the end decided that Hayek's name had much more resonance with potential readers. That may have been a mistake...

1. I think that the environmental consequences of our industrial civilization is a major part of whatever the grand narrative of the 21st century will be, and one reason for choosing 2010 as an ending point is that the global-warming climate signal had not then fully emerged from the year-to-year weather-fluctuation noise.

2. I can't make up my mind whether the Soviet Union boosted the Western left (people on the right telling each other to be quiet—we need to construct an anti-totalitarian popular front after WWII) or hobbled it (all Democrats are commies). So I dodged the question...

3. I only had 600 pages! And I felt I should spend more time on the decline of social democracy (which still puzzles me) than on the system at its apogee...

Again, thanks much for your PS review.